Researchers find security risk 'feature flaw' in new firewalls - or did they?

How the firewall vulnerability outlined by the BugSec-Cynet team works.

Are millions of enterprise users, who rely on next-generation firewalls for protection, vulnerable to a massive, by-design security flaw that can allow hackers to sneak onto their networks to do as they please?

A major debate has erupted in the security community over that question over the past few weeks.

According to BugSec and Cynet, two Israeli cybersecurity firms that worked together on the research, the answer is a distressing, 'yes'.

"This vulnerability could potentially be a big risk for organizations," Stas Volfus, head of offensive security for the team, said. "It's built into all next-generation firewalls, and if we were able to exploit it, hackers will be able to do so as well."

On the other hand, other security professionals correctly point out that this vulnerability is nothing new, with one blogpost going so far as to call the claim "false".

Next-generation firewalls have been touted as the future for protecting online applications.

Unlike traditional firewalls, which inspect ports to ensure they are being properly used -- an increasingly irrelevant exercise given that so many apps nowadays vary their use of ports -- next-generation firewalls examine the applications themselves, using various methods to determine what it is being presented with, where the traffic is coming from, and whether it is safe.

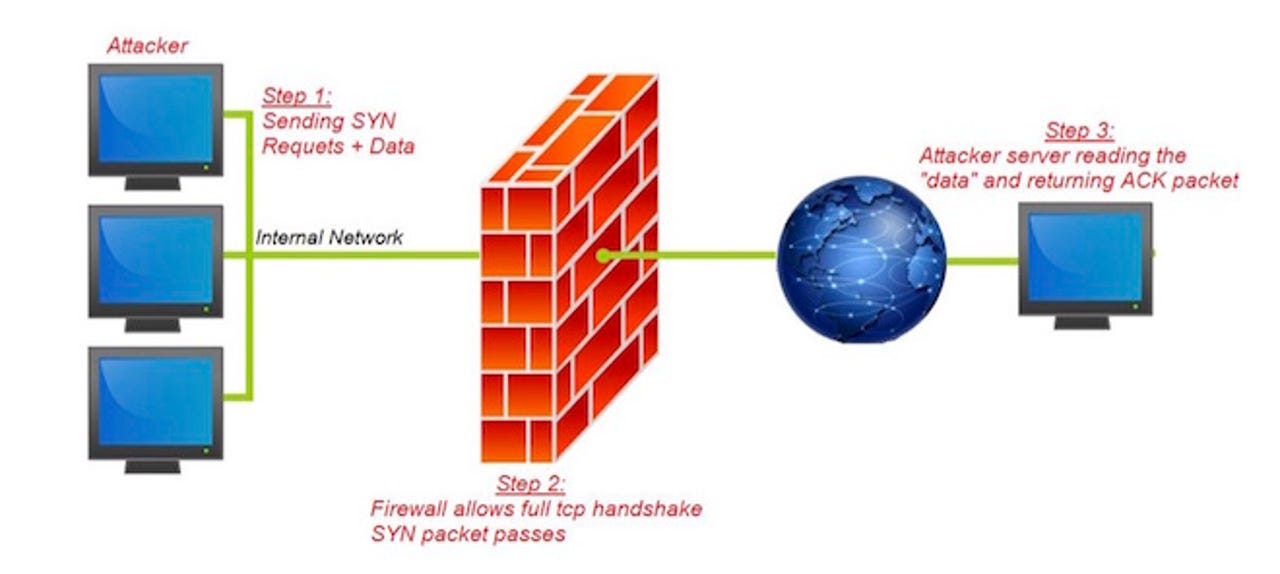

And that's the problem, the Israeli team claims. To do this, the firewall allows a full TCP handshake regardless of the packet destination. It's the only way for the firewall to gather enough content for it to identify which application protocol is being used.

As part of that access, the firewalls allow web-browsing HTTP/S traffic from the LAN environment to specific locations on the internet in a process called URL-filtering.

This approach enabled the security research team to perform a full TCP Handshake via the HTTP port with a command-and-control server hosted by BugSec.

From there, the team was able to forge messages and tunnel them out through the TCP handshake process, bypassing the firewall to any destination on the internet, regardless of firewall rules and restrictions.

Sounds dangerous, and it is, Volfus said. "What this means is that malware can be gotten through to a server in the form of a legitimate-looking application, and send what appear to be perfectly kosher messages to a C&C server. Many of these firewalls inspect the application layer and then attach a predesigned policy."

All criminals have to do is hide their malware payload in innocent-looking application traffic, and they're in.

It is important to note that all traffic sent to the command-and-control server after the TCP handshake process was blocked immediately by the firewall, as the policy manager categorized the researchers' traffic as 'unknown-TCP' and the HTTP destination wasn't allowed. In addition, Volfus said, the team is unaware of this vulnerability having been used by hackers so far.

According to security firm Palo Alto Networks, there's a good reason for that. In a blogpost, the company said, "Firewall policy is never violated", and explained that a next-generation firewall will always inspect its rule base before even deciding whether or not to allow traffic through. Rules can be set as tightly as needed, to prevent bad data seeping in.

BugSec-Cynet informed vendors of the issue, with at least one saying it did not see the findings as a security threat. The vendor said once its state machine proceeded beyond the TCP handshake, it would recognize the application, matching a subsequent rule that applied to application traffic.

The vendor added that if it did not recognize the application, it would treat the session as unknown-TCP and, again, perform an additional security policy lookup to decide whether to allow or block the traffic.

That's if the additional policy exists, of course. But the nature of firewalls, and the general attitude to security, is to rely on what comes out of the box. The mere existence of this exploitable vulnerability is problem enough, as far as the Israeli team is concerned.

"Obviously we can't go back to the old TCP firewalls, and the idea of application security on firewalls is an important one," Volfus said. "But if I were a customer of one of these vendors, I would be asking some hard questions."