Steve Jobs: The NeXT Years

For the last decade, you've known Steve Jobs as the wizard-king of Apple. From his throne room at Macworld or Apple's developers conference, he would strive forth in his robes of office--a black turtleneck and jeans-announce "One more thing" and determine the shape of computing for the next year. Hate him or love him, he was the trend-setter not just for Apple, but for all computing. And, just like the Wizard of Oz, outside his throne room, he would have nothing to do with you. That wasn't the Jobs I met in 1989.

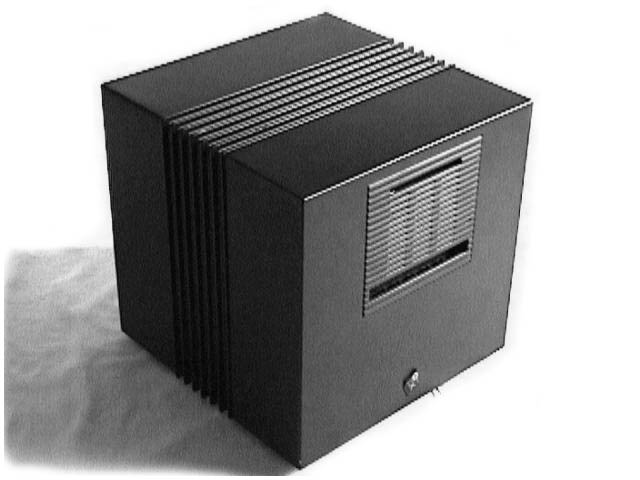

The Jobs I knew, still chastened by his forced departure from Apple in 1985, was happy to talk to the press. I think he rather liked me since I was one of the few people who took his new company, NeXT; his new PCs, the NeXT Cube and the NeXTStation, and his new operating system, NeXTStep seriously.

You see, this wasn't the jobs whose merest glance was analyzed by bloggers around the world for a hint of what Apple might do next. No, this was the Jobs pushing a BSD Unix-based operating system and incredibly expensive computers to a world that thought the only realistic alternative to Windows might conceivably be OS/2. Steve Jobs? He was the crank who made great stuff that was far too expensive for most users.

They were wrong of course. What Jobs was doing in the late 80s and early 90s, freed of the restraints of Apple's then CEO John Scully, was creating the foundation of not just Mac OS X, but what would prove to be model for today's Apple.

The NeXT Computer, and its follow-up, the NeXT Cube looking nothing like any other computer of their day. Unlike Apple's rather silly battles today to claim that Samsung's Galaxy Tab 10.1's design violates the look of Apple's iPad, the NeXT hardware really did look like nothing else on the marketplace.

And, like today's Apple computers, phones and tablets, NeXT hardware came at a premium price: The very first NeXT computers, which were only available to educational institutions, cost $6,500. They looked great, had features, like a mageto-optical disc for storage, that no one else had, and they cost a fortune. Hmmm... where have I heard of hardware like that recently? Could it be Apple? Why, yes, yes it is.

The second generation would cost even more. Few of them were sold, but, then as now, cutting edge technology people lusted for them the way an Apple fanboy lists for an iPhone 5 today. Mea culpa, one of my proudest possessions in those days was my NeXTStation Color. It cost me five grand back in 1993. Everyone, but everyone, said how great the NeXT hardware while at the same time saying it was far too expensive to ever really become a success.

At the same time though, if you doing really cutting edge work, you wanted a NeXT. Sir Tim Berners-Lee, for example, created the first Web server and browser on NeXT computers.

These machines all ran NeXTStep. NeXTStep ran on top of a multi-threaded, multi-processing microkernel operating system: Mach. On top of this micro-kernel, NeXTStep used BSD Unix. What most users saw was the Workspace Manager. This was an object-oriented GUI. You could take its individual elements, icons, menus and windows, apart and sew them back together to form an interface's that's custom tailored for the way you work.

NeXTStep's Workspace Manager included "shelf" for files and an "application dock" for programs. On NeXTStep's shelves you could place any frequently accessed programs, directories, or files. Launching programs and working with files is all accomplished by click, drag and drop.

Does this sound familiar? It should. NeXTStep, and its components, are the direct ancestors of today's Mac OS X. Without NeXTStep, and its Unix foundation, there would be no Mac OS X. A NeXTStep user from 1993 would have little trouble using 2011's Mac OS X Lion.

While NeXT computers and NeXTStep were gaining fans but little market share, Apple was having serious trouble. Under Scully and then Michael Spindler, the company continued to flounder. When Gil Amelio took Apple over in 1996, he appointed Ellen Hancock to determine Apple's operating system future.

Hancock quickly decided that the existing plans to upgrade the Mac's operating system to Copland were a complete mess. She recommended that Apple should look outside its corporate walls to find its new operating system. The company did and by 1996 NeXTStep was selected to become Apple's future operating system, Mac OS X. Apple bought NeXT and Jobs, in 1997, returned to Apple as a "consultant." By September 1997, Jobs was back in the saddle as CEO.

The Jobs who returned to Apple wasn't the same man who'd left. He was even more determined that Apple would be run his way and no other way. He'd like being in charge at NeXT and he wasn't going to re-invent an Apple "beset by financial losses, disappointing sales and eroding market share," to anyone else's vision save his own.

That meant building unique new hardware. At NeXT, he had done that with the NeXT Cube. In more recent years he's done this with the iPod, iPhone, and iPad. In addition, just as with NeXT hardware, Apple would charge a premium price for its innovative designs and quality workmanship. It means, while barely acknowledging it in recent years, that Mac OS X is built on an open-source Unix foundation.

NeXT turned out to be Jobs' blueprint for today's Apple. I don't know what will happen to Apple tomorrow. It worries me that, instead of relying on superior design and production values, Apple has recently turned to intellectual property lawsuits to maintain its market momentum. Maybe it's just a sign of the times, as one software company after another exploits the broken patent system to try to stifle competition, but I fear it's more a sign that Jobs' failing health had left him unable to follow his original, NeXT-based technology vision.

Related Stories:

Steve Jobs: Thinking through his CEO legacy

Steve Jobs retrospective (Video)

Steve Jobs: Apple's greatest legacy or its biggest obstacle?

Steve Jobs resigns: Now Apple's succession plan to be put to test