The Lego datacentre

It used to be that datacentres were more art than science; wonderfully baroque constructions of servers and cabling, the very temples of modern computation. The wiring that linked the servers in some datacentres was so convoluted that it was easier to lay a new cable than trace the route of an old one…

Then came co-location centres: there were cages full of servers, structured cabling, masses of fans. They were so secure you had to register your biometrics just to get in the door to fix your own machines – and the biggest kept armed guards at the doors. They were full of blinking lights and humming boxes, all surrounded by the rush of forced air cooling.

But they were inefficient. One server per application, or per user.

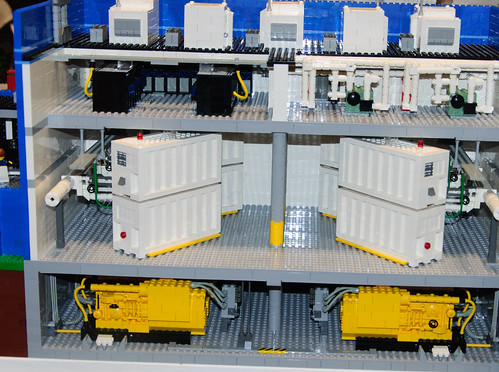

The cloud, they say, changes everything. That's certainly true for datacentres. A cloud datacentre is a very different class of beast from a large colocation facility. Instead of the familiar machine room and racks of servers, there's a huge warehouse, full of containers. The servers in those containers aren’t the familiar devices in our racks. They’re specially designed, sold in the tens of thousands, but instead of whirring fans and spinning disks, they minimise moving parts by being designed for passive cooling and by using SSDs for storage. They're also in very different places, where the power is cheap, and where the natural environment keeps cooling costs to a minimum. You'll find them near hydroelectric dams, or other sources of natural energy, like Iceland's geothermal fields.

The containers themselves are intended to be trucked in, left in place for three years, and then sent back for recycling. All they need is a connection for power, another for networking, and a hose for the water in the passive cooling system. There shouldn't be any needed for anyone to enter to repair a server – instead any server that fails is just shut down, and its load sent off to another host machine somewhere else in the cloud. If too many machines in one container fail, it’s easy to replace the whole thing – and if you need more compute power, all you need to do is plug in a new container.

It's just like Lego.

That probably explains why at Microsoft's TechEd event in Orlando last week, the Redmond giant's Office 365 group decided to show off their cloud datacentres in a rather different way, as a Lego diorama. A hydroelectric dam filled on side of the model, with a city in the other, and a cross-section of a cloud datacentre down one side.

"Pics or it didn’t happen" they say out in the wilds of the Internets, and so we took more than a few (and a couple of 360-degree panoramas just to round things off).

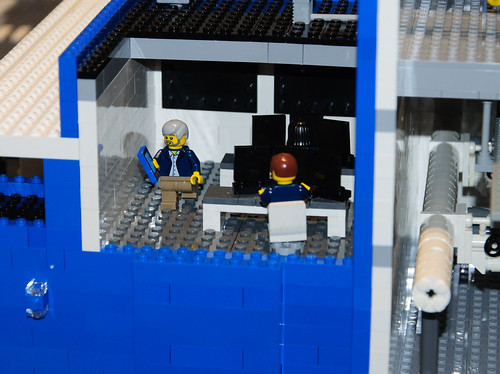

In a Lego network-operating centre minifigs with tablets and terminals keep an eye on their cloud services.

Below them containers of servers fill the cloud datacenter.

Huge generators standby to keep the system up, if the power supplies fail.

And the old-school datacentres? Full of cobwebs.

Simon Bisson