Trip report: Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan has probably had more Google hits in the last month than ever before in its short existence as a republic independent of the Soviet Union - since 1992 barely older than Google itself. That's due to three things: the recent visit of Nursultan Nazarbayev, Kazakhstan's autocratic ruler, who has been in charge since he became a leader of the then Soviet Republic in the 1980s; Kazakhstan's controversial attempt to lead the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, for which many parties consider it unqualified by virtue of its own internal opacity and autocratic government; and the satire of Jewish comedian Sasha Ali G. Cohen, stage name Borat, which have gained great publicity through the Kazakh government's ham-handed attempts to shut him up (by lodging a protest with the USG).

Countering all these deficiencies are the country's huge oil reserves, which allow it to mingle in polite geopolitical society, and also indirectly to buy off a population that might otherwise be more restive. I spent a weekend there a week ago. It has taken me that long to digest things, and there have also been some subsequent events.

I was there mostly because it was a convenient stop between Athens and Bangalore (if you like traveling!), and because I'm the board member of the National Endowment for Democracy responsible for the region. (I speak Russian and have great familiarity with the former Soviet Union, but I had been in Kazakhstan only once before.)

Miriam Lanskoy, NED program officer for Eurasia, happened to be there that weekend too, and she let me come along with her as she rode her circuit. Our first meeting (after a brief excursion to buy a genuine Speedo bathing cap for $5 in a local sporting goods emporium) was lunch with the "party institutes," the National Democratic Institute, chaired by Madeleine Albright, and the International Republican Institute, chaired by John McCain. They are arms of the NED, whose overall mission is to support the spread of democracy (but not of specific parties) wherever it may be springing to life. It does that mostly through grants to in-region NGOs. The Institutes, by contrast, run programs of their own: Mostly, they train any aspiring political organizers who are interested in the mechanics of party activism: direct mail, message development, media training and the like.

To be candid, this notion had left me a little uneasy until now. How can you non-partisanly train people in partisanship? But after meeting the players - Josh Bergin of the IRI and Mary Cummins and Sameera Ali of the NDI - and hearing them describe their work, I felt a lot better about the whole thing. They are indeed mostly going around teaching people how to run a mail-merge program, how to craft a clear message, how to measure public opinion, and so forth. There are certainly ways you could mis-apply the learning, but in this world where 1490 of 1500 newspapers are government-owned or aligned, teaching people the nuts and bolts of bottom-up communications seems pretty one-sidedly good.

Yet, as it happens, the activities of NDI and IRI have been in suspension in Kazakhstan since last spring, courtesy of the Kazakh government. This issue was raised in DC during Nazarbayev's visit, we hear, but there has been little news since. This report, in Governo-Kazakh, does little to clarify things.

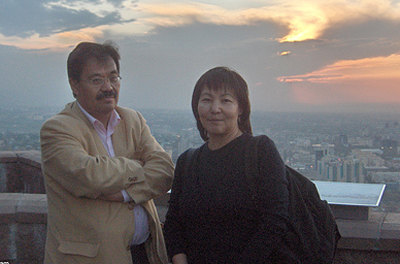

Next we went to Club Polyton, a lively discussion club held in a largish room off a warren of offices, run by Nurbulat Massanov, a political scientist and scholar of Kazakh history and national identity. He had devoted his life to fostering political discussion and was able to get visiting dignitaries of all kinds to stop by his club to speak to and with local activists. The audience that Saturday probably skewed a little techy because of my presence: it comprised the leaders of the leading political Websites, kub.kz and zona.kz, and the Website of Respublika, the leading independent newspaper (which just that morning had carried a statement by local NGOs advising against Kazakhstan's chairmanship of the OSCE). We had a lively discussion.

This community is active and engaged among themselves, but they don't reach much of the broader public. A typical home/small business Internet account at 512k - but hardly affordable by a typical home - costs $300/month, so Internet users number about half a million of Kazakhstan's 15 million people (3 percent). Censorship is active, but it's not like in China (where you often know your censor and can negotiate, and the blocking often applies to search queries rather than to the sites themselves): In Kazakhstan, sites are simply blocked. There's certainly a correlation between political edginess and blocking, but it's not precise or predictable. This is a country, remember, where two opposition leaders, (Zamanbek Nurkadilov andAltynbek Sarsenbayev) were murdered in the last year, so no one wants to test things too far.

One person mentioned that the government had recently disclosed the salary of the president of the monopoly telecom provider, 51-percent-owned by the government and 49-percent-owned by private, not very transparent interests. He makes $365,000 per month, plus a $2-million annual bonus. That aroused predictable outrage, but the real question people were interested in was who had caused the news to be released and why?

I suggested that one way the group could be active without pushing things too far would be to launch a campaign for cheaper internet access. Even with a monopoly still in place, lower prices would likely mean more revenues, with price elasticity turning a 50 percent drop in prices into more than double the number of accounts over time. (It was a challenge to explain that in Russian, where both the words and the concepts are unfamiliar.)

But, Massanov told me, in paraphrase, "Don't be naive. This isn't just about money; it's about control. They don't want us to have access…."

Perhaps, I countered, but you could get quite a large part of the business community - and perhaps some of the trade and commercial people in the government - on your side.

City arrest

After Polyton, we went to see Galymzhan Zhakiyanov,I put the same case for cheaper Internet access to Zhakiyanov, and he considered it more enthusiastically, but I don't think it will be a priority. (He also asked if I could give him technical advice on his website; I demurred. But I do think some kind of general back-end infrastructure service, provided by the NED or some other organization, would be tremendously useful for and popular among NGOs in the countries the NED serves.)

After that, we went to a reception for the opening of the Eurasia Foundation's new EF Central Asia, which has just opened, run by longtime EFer Andrew Wilson. It is an independent but affiliated NGO, with its own management and some of its own funding, including from corporations such as Philip Morris, AES Corporation, Microsoft Kazakhstan, TengizChevroil and PetroKazakhstan. The mother EF, like the NED, began as a government-funded institution, but it has diversified its revenue sources and is more focused on civil-society projects in general rather than democracy and governance in particular.

Sunday - site visits

On Sunday, we went to see some of the people whom all this activity is supposed to empower. Sergei Solyanik took us there; he works for Green Salvation, an environmental NGO, First, a family - mother and daughter, the father was ill - whose house is overshadowed by a high-voltage power line built a couple of years ago. An underground cable broke, and the local government decided to save money - against community wishes - by replacing it with a kilometer-long open-air power line of the sort you sometimes see out in wild country, but rarely near human settlements. For starters, the line itself is an electrical and fire hazard; this one was especially scary since it was no more than 20 meters away from an above-ground gas pipe in many places. Second, the community believes that it is causing numerous health problems among the people who live near it. That's harder to determine, but it certainly contributes to the community's almost unanimous but still ignored desire to see the things buried underground. As usual, there's a lack of clarity as to how this happened, where the money went, and whether the cable will or will not be buried shortly. Green Salvation has filed a suit on behalf of the community, and won its case in international court under Aarhus Convention, but the local government has not implemented the decision of the international convention body.

Next we went out to the town of Shanirak [photos: http://www.flickr.com/photos/edyson/271562995/in/photostream/], , which used to be outside city limits but is now under the rule of the ever-expanding Almaty municipality. Again, a brief version of a murky story: There's a settlement of about 1500 people who came here from all parts of Kazakhstan and built their own homes. They have documents from the old government officials certifying that they have paid for the right to live on this land. Now the new government says those old documents are invalid...and besides, the water table there is too low and so on. They have cut off electricity and water.

There's some question whether the old government had the right to sell the land to the settlers, or where the money went to, but certainly the settlers relied on those representations. Meanwhile, there are settlements nearby - one of retired policemen - that just don't have the same problems under the new Almaty government. The spot the settlers occupy is slated to be used for a new shopping mall.

As we stood out in the sunshine, we could see destroyed houses, amidst standing houses that also looked fairly decrepit. There were outhouses, and one shack with a plastic bucket atop, which passed for a shower. Various people came up and joined the conversation: they could all remember the time in July when city authorities, along with security police and bulldozers, showed up to raze the buildings. The villagers protested, standing in front of their homes. The most voluble o the women told us how she had doused herself and her children with gasoline, and threatened to strike a match. The forces stood down, but not without wrecking part of her house. More alterations ensued, and some rocks were thrown. The police claimed that the settlers had stockpiled rocks as weapons; the settlers said they were just construction materials lying around. At the end of the day, one of the policemen had been burned to death in a gasoline fire. The police attributed it to the settlers; the settlers attributed it to a provocateur.

Later, we visited a similar place elsewhere around the city - a similar story, but with more destruction, called Bakai. In this case, about 400 houses were destroyed even though the city had cases against only 35. People were still living there amidst the ruins. Again, the story was murky, and some people, who had either paid off officials or paid for legitimate approvals (the difference wasn't clear) were spared

. Another view, but not entirely

Over dinner, it was my turn to show Miriam and her colleague Rebekah Boone another side of Kazakhstan - dinner with the owner (from Russia) and the manager of a small local business with about 10 employees. They provide software and support to local customers. They are not "connected" to anyone in power, and they are doing reasonably well. Yet they prefer not to be named, which probably says as much as anything about the state of things in Kazakhsta

n.

The manager, call him Nur-Nur (which means Nice-Nice), had read about the events in Shanirak and Bakai ; as far as he knew, they concerned a bunch of criminal elements who had attempted to steal government land and were terrorizing their neighborhoods. But…the story wasn't so simple. It turns out Nur-Nur's own house is under threat: The government also plans to build some more modern buildings in his neighborhood, and they will demolish his house. He will get compensation; however, he doubts it will reflect the true value of the property. "Why don't you get together with the neighbors to protest?" I asked, waiting to espouse the virtues of collective action. But he didn't think that would work. His neighbors already think he's suspect, since his house (built by his father) is considerably nicer than theirs. So he plans to go it alone, and has hired a lawyer.

As for the rest, there was agreement that the climate for small business - as long as it doesn't tangle with anyone - is more favorable in Kazakhstan than in Russia. Big business may mostly have ties to the Nazarbayev family, but there is not quite as much of the petty corruption you find in Russia. Nazarbayev has tighter control than Putin; it's a small country after all.

Subsequent events

On my flight out of Kazakhstan I ended up sitting next to the Foreign Minister, Kassymzhomart Tokaev. We chatted, and I didn't mention either Borat or Shanirak. I didn't think there was much point, and I was more interested in inserting good ideas into the national discussion than scoring points. So we did talk about telecom, and I stressed once again that lower prices would do nothing but good for the country. Of course he's not the minister of either telecom or economics, but ideas do get through. Just as Google is good for China, so, I think, would the Internet be good for Kazakhstan.

Later in the week, I heard from Miriam that Nurbulat Massanov had suddenly died - not under suspicious circumstances - of a known food allergy last Tuesday. He'd had lunch with a friend at a restaurant and got ill several hours later a medical emergency team showed up, but they couldn't save him. It was truly an accident - and also a terrible tragedy, both for his friends and family, and for Kazakhstan. People of such commitment and courage are rare, and Kazakhstan needs more of them.