ZDNET Multiplexer

mul-ti-plexer-er. noun. A device, in electronics, that synthesizes disparate data signals into a single, uniform output. ZDNET Multiplexer merges various perspectives, media types, and data sources and synthesizes them into one clear message, via a sponsored blog.

ZDNET Multiplexer allows marketers to connect directly with the ZDNET community by enabling them to blog on the ZDNET publishing platform. Content on ZDNET Multiplexer blogs is produced in association with the sponsor and is not part of ZDNET's editorial content.

Windows 11: Do I Need to Upgrade or Replace My PCs?

Sometime shortly after the beginning of 2022, you're going to find yourself faced with the choice of whether to upgrade your machines that run Microsoft Windows 10 with the new version, Windows 11. There are plenty of good reasons to make the upgrade, notably the significant security improvements. But there are also reasons not to make the switch.

The biggest reason to stick with Windows 10 is that there may be PCs that simply won't run the new OS. Microsoft has provided a list of minimum system requirements needed before a computer can run Windows 11.

Nearly any computer made in the last decade can meet some of the requirements. For example, finding a computer with a 64-bit processor and two or more cores operating at 1 gigahertz is pretty easy.

Finding 4 gigabytes of memory and 64 gigabytes of storage is also within the range of most computers, and for those that aren't, adding more is not very complicated. The OS requires a high-definition display of at least 9 inches with 8 bits per color channel, which is also pretty standard, but some older laptops and netbooks may not make the cut.

Beyond that, however, things can get a little dicey. The computer needs to have a supported processor from Intel, AMD or Qualcomm. It also needs to have UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface) with secure boot, which is something that even some recent computers may not have. It also needs a Trusted Platform Module (TPM) version 2.0 (essentially a dedicated security chip), which is also a fairly recent feature.

The way to find out whether your computer meets these requirements is to grab your mouse and right-click on the Windows Start button in the lower left corner. In the menu that appears, click on "Device Manager."

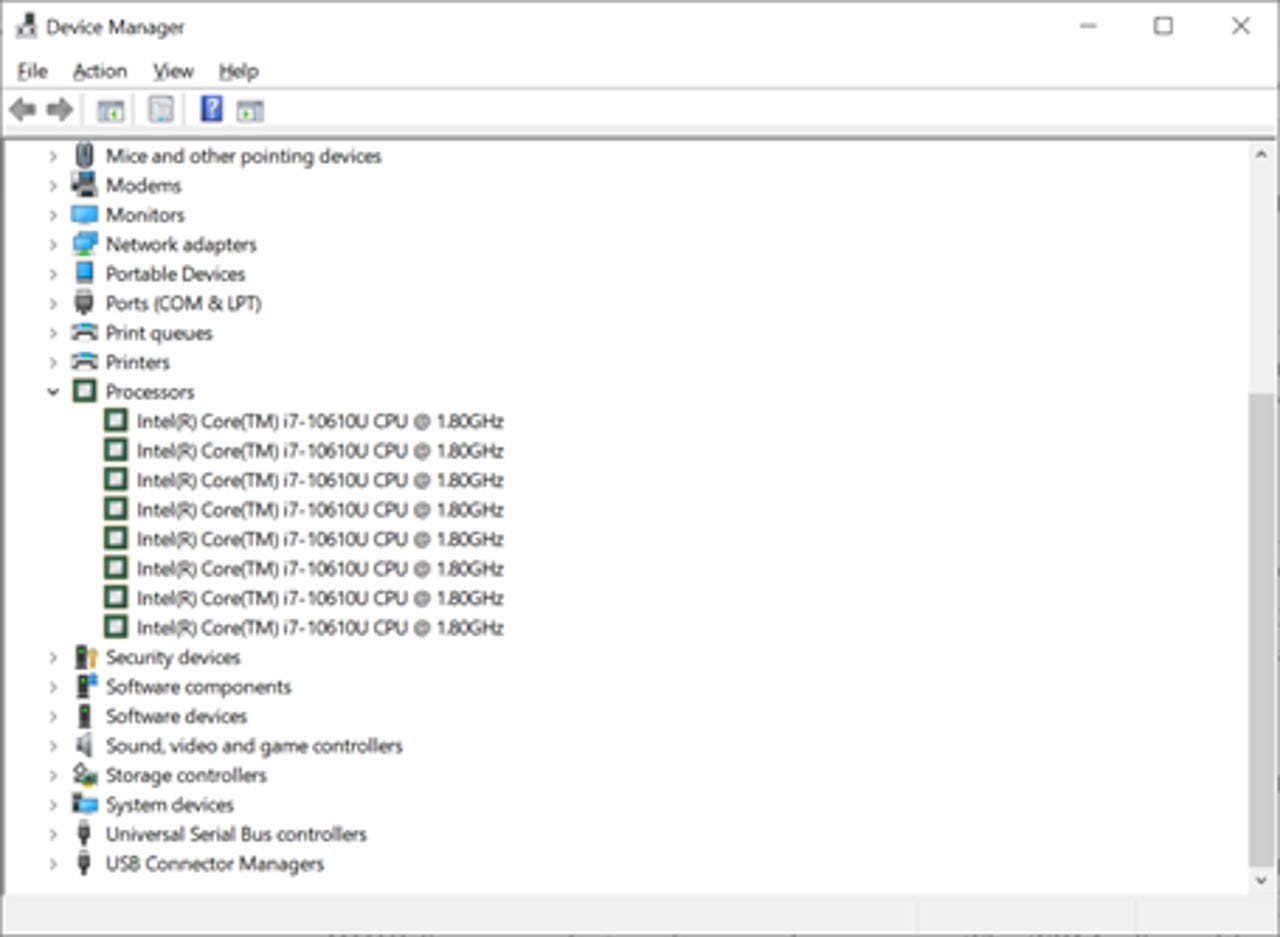

In the window that appears, you'll see a long list of choices. Three of those choices will tell you what you need to know. First on the alphabetical list is Processors. Click on the arrow to the left of that. There will be a list showing multiple entries for the same processor. It'll say something like: "Intel Core (TM)" followed by a series of letters and numbers. Write down exactly what appears on any one of the items in the list.

Going back to the Device Manager list, continue down until you see Security Devices, and click on that arrow to the left. If you have a TPM, it will appear. If it says Trusted Platform Module 2.0, the computer meets that Windows 11 requirement.

Continue down the list to the System Devices entry, and once again, click on the arrow on the left of the entry. Again, you'll see a long list of entries. Scroll down the list until you see "Microsoft UEFI Compliant System." If it's there, you're meeting the Windows 11 requirements.

Now, find where you wrote down the processor details, and find the list of supported processors for the type of processor on your computer. (The links to those lists are above.) Once the list is open in a browser window, press CTRL-F, for 'find.' You'll see a small text entry box open at the top of your browser.

Click on the text entry box, then type or paste in the identifying information about your processor. For example, if your processor is listed as "Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-7600U CPU @ 2.80GHz" then you can type in "7600U" and see what shows up. You may find, as was the case with this processor, that it's not on the list, meaning that your computer's processor is not compatible with Windows 11.

Upgrade or replace?

This is where you need to decide what to do. It may be possible to upgrade the processor, for example, and if you're confident in what you're doing, you can try. But if you're missing the UEFI or the TPM 2.0, you probably can't upgrade your computer to work with Windows 11. Upgrading the BIOS to UEFI might be possible with new BIOS firmware, but such upgrades are rare. The TPM, though, can't be upgraded, and it can't be added if it's not there.

If your PC doesn't meet any of these three basic requirements, then your computer can't run Windows 11. You have four years, until October 2025, to run Windows 10 while it's still supported by Microsoft. Given that few businesses wait that long to replace their computers, it's just a matter of scheduling your non-compliant machines for replacement before then.

But what about computers that can run (perhaps just barely) Windows 11, or can be upgraded so they will? That's when you need to decide when it makes economic sense to replace a computer vs. keeping it. If the PC can be brought into compliance with an upgrade, does it make sense to spend the money and the labor hours on a computer that's already old? Generally, if a computer is 3 years old, it's time to think about replacing it anyway. And if it's nearing the 3-year mark, by the time you buy the next computer, it'll be running Windows 11.

In fact, if you're replacing your computers before the end of the year, most manufacturers, including Dell, will be selling machines with Windows 11 pre-installed. Microsoft already has a list of Windows 11-compatible machines on its Windows 11 website. In addition, you can follow this link to see upgrade-ready PCs available from Dell.