Google Chrome's breakneck pace: innovation or version inflation?

According to the About dialog box, my installation of Google Chrome just rolled over to version 16. When the year began, it was on version 8.

That's eight new versions in one year, an average of one new "major" release every six weeks, not counting the two or three bug fixes that Google's updater delivers in between the big milestones.

Delivering two new packages every calendar quarter and assigning a major version number to each one makes it appear that Google is innovating at lightning speed while its rivals plod along. Indeed, that numbering scheme was enough to convince Mozilla to change its release schedule. Enterprise customers weren't very happy when Firefox adopted the same new-version-every-six-weeks model.

But one thing has been bugging me all year. Despite the rapidly incrementing major version numbers, Chrome doesn't really seem to have changed all that much this year. Are those formal releases really all that different? Or is Google's "innovation" really just a new form of inflation, targeting version numbers?

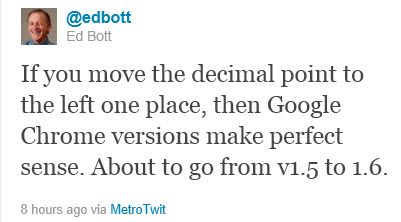

This morning I shared a wisecrack on Twitter that turned out to be more truthful than I realized:

Indeed, the closer I look at what's really in each new Chrome release, the more I'm convinced that most of these releases are pretty minor in the grand scheme of things. The move from version 15 to 16 really does look more like a minor upgrade from 1.5 to 1.6.

That's certainly true if you look at support for HTML5 standards. Given the constant drumbeat over the importance of HTML5 to the future of the web, one would think it's a key focus for Chrome developers. And yet all that incrementing has barely made a difference in HTML5 compatibility this year, as measured by independent test sites.

Exhibit A: The HTML5 Test site runs browsers through a battery of tests and then assigns a score to each one. A perfect score would be 450. Here's how the last six versions of Google Chrome have fared:

- 11.0.696: 338

- 12.0.742: 339

- 13.0.782: 341

- 14.0.835: 340

- 15.0.874: 342

- 16.0.891: 343

Those are downright microscopic changes over a period of roughly eight months, with only one or two tiny features at a time being changed. And the gap between HTML5 today and the future ideal is still massive.

Likewise, the Browserscope summary scores, which track functionality for web developers, include three versions of Chrome, 15 through 17, with identical overall scores of 87/100 for each one. On the Browserscope HTML5 2.2 test, compatibility scores actually decreased between versions 15 and 16, dropping from 332 to 317. That's the sort of thing you expect from a beta release, not from an upgrade that should be pushing standards support forward.

Looking beyond HTML5, some of the change logs for recent Chrome releases (as described in its Wikipedia page) are so thin that they make a mockery of the major version number strategy. In version 11.0.696, for example, only two additions appeared on the list: "HTML5 Speech Input API" is useful to developers but arguably a yawner for end users. The second change? An "updated icon." I would expect much more from a release that goes to 11.

Image via Wikipedia

Some of the changes listed for this year's whole-number releases are not so much about the web as they are about Google's services. Version 13.0.782, for example, introduced Instant Pages, a feature that downloads and pre-renders the top result in a Google search—it's a variation on prefetching techniques that have been around for a long time, and only of benefit in Google searches. The other substantive change in v13 was a change to the print preview interface. Again, hardly the sort of thing that would traditionally warrant a new major version number.

And when my ZDNet colleague Steven J. Vaughan-Nichols, a longtime Google fan, reviewed Chrome version 16 today, he acknowledged: "No, there’s nothing new in capital letters in this release." It's slower than it once was, and the flagship feature in this release, multiple user profiles, seems half-baked based on Steven's description:

[Y]ou can sync multiple users to one copy of Chrome. So, for example, you can have multiple people via their Gmail accounts, running their own Chrome settings. ...

So far, so good, but, there’s no security between logins. She can see all my settings and I can see hers. You may be OK with that, but I’m not and I can’t see it in a work environment where people share PCs.

His conclusion? "at this point I don’t see [this feature] as being that useful." In other words, perhaps it should have been released to developers and early adopters, not to the general public.

Would the Web be worse off if Google decided to call each one of those a point release or even a beta? I don't think so.

Don't get me wrong. I think Google has in general done a great job with Chrome. It's fast, it has very few compatibility problems in my experience (although I regularly hear a few screams when a new version appears in the wild). And Google has done an admirable job with its auto-update process, which seems to work well—at least for consumers. But a predictable major release cycle of every six months, with optional updates every six weeks for developers and bleeding-edge users to experiment with new stuff, would be a far more sensible approach. That approach seems to work well for the Linux community.

Perhaps Google's motive with its fast-twitch release cycle is to unnerve its competitors. It seemed to do that with Mozilla, which is struggling to keep that pace. So far Microsoft hasn't taken the bait. It's still sticking with its annual release cycle, although it has moved to automatic updates in an effort to forcibly drag diehard IE6 and IE7 users into more modern browsers.

The bottom line? Next time someone talks about Google's rapid pace of innovation with Chrome, take that argument with a grain of salt.