Is Microsoft finally ready to get serious about online privacy?

It is tempting to look for short-term motives for every action by a big technology company. Case in point: with the debut of the Windows 8 Release Preview last week, Microsoft enabled the “Do Not Track” setting in Internet Explorer 10.

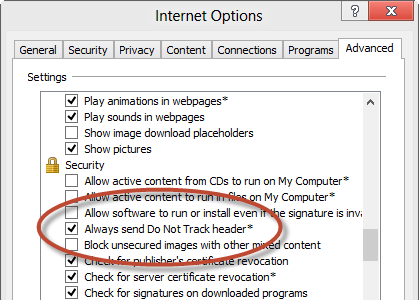

Here's what the setting looks like on a brand-new Windows 8 Release Preview system I just set up:

That’s a first for any browser on any platform, and arguably a provocative move. My colleague Andrew Nusca views it as a message to the ad industry: Microsoft to advertisers: Drop dead.

Jake Ludington, who’s been working in online marketing for as long as I can remember, sees the move as an attack on Google:

Microsoft seems to be declaring war on two of Google’s business units by enabling the Do Not Track (DNT) feature in Internet Explorer 10 by default.

The reality is that Microsoft’s concern over online privacy goes back many years, and this move is just the latest in a consistent chain of events going back several years.

Microsoft designed extensive privacy controls into Internet Explorer more than four years ago, and the developers who built IE8 wanted to turn those privacy settings on by default. But the browser team lost an internal struggle within Microsoft. The Wall Street Journal reported the story two years later:

In early 2008, Microsoft Corp.’s product planners for the Internet Explorer 8.0 browser intended to give users a simple, effective way to avoid being tracked online. They wanted to design the software to automatically thwart common tracking tools, unless a user deliberately switched to settings affording less privacy. [emphasis added]

That triggered heated debate inside Microsoft. As the leading maker of Web browsers, the gateway software to the Internet, Microsoft must balance conflicting interests: helping people surf the Web with its browser to keep their mouse clicks private, and helping advertisers who want to see those clicks.

In the end, the product planners lost a key part of the debate. The winners: executives who argued that giving automatic privacy to consumers would make it tougher for Microsoft to profit from selling online ads. Microsoft built its browser so that users must deliberately turn on privacy settings every time they start up the software.

In 2011, with IE9, Microsoft upped the ante, introducing a feature called Tracking Protection. When I first saw it it in action, I noted its disruptive potential:

The more closely I look at the new Tracking Protection feature in Internet Explorer 9, the more astonished I am that it came from one of the world’s largest corporations.

If Internet Explorer 9 becomes widely adopted and if Tracking Protection is widely used—and those are two tricky assumptions—it has the potential to seriously disrupt the online advertising business.

Do Not Track and Tracking Protection attack the problems of privacy from opposite direction. Do Not Track sends a signal to web sites and advertisers telling them that the user making the request doesn’t want to be tracked. It’s up to the web site owner to voluntarily comply with that request.

Tracking Protection works from the client side, blocking third-party cookies used by ad networks and analytics firms. The feature doesn’t rely on voluntary compliance by advertisers; instead, Internet Explorer simply refuses to make the third-party connection, and the company that wants to do the tracking doesn’t know you exist.

Advertisers didn’t freak out over Tracking Protection last year, because they know most people will never turn it on. Although I use the feature regularly, I know I’m in a tiny minority. I’d be shocked if 1 in 1000 people who use the Internet employ any kind of privacy protection tools.

What has the online ad industry up in arms over this latest move is that they know that flipping the defaults really does make a difference. If online advertisers (and make no mistake about it, Google is at its heart an ad company) had to convince users to change the default setting and enable online tracking, they know that most people would refuse.

Personally, I don’t think Microsoft has gone far enough yet in terms of getting tough about online privacy. If they were really serious, they’d refine the Tracking Protection feature, make it usable by mere mortals, and turn it on by default.

I don’t expect that to happen, but if it did, the screams from the advertising industry would be downright deafening.

See also:

- Microsoft to advertisers: Drop dead

- CNET: Microsoft ticks off advertisers with IE10 'Do Not Track' policy

- Good Microsoft versus Bad Microsoft on privacy

- IE9 and Tracking Protection: Microsoft disrupts the online ad business

- Internet Explorer 9 Tracking Protection: how it works

- Google defense cites study arguing for stronger privacy regulation