Farmers are firing automatic lasers at hungry birds

Birds decimate crops, costing farmers tens of millions of dollars each year.

To stop that from happening, farmers have employed all kinds of gimmicks, from traditional scarecrows to nets.

If you're ever driving through bucolic pastures and hear a boom suggestive of artillery, it's probably a propane gun set off to scare away birds.

But a combination of IoT, automation, and solar-powered lasers could be the golden ticket.

Recently, Justin Meduri, Farm Operations Manager of Meduri Farms, which raises blueberries in Jefferson, Oregon, was looking for a way to mitigate crop damage inflicted by birds. Annually, Meduri was losing about 25 percent of overall potential crop volume, which equates to around 100,000 USD in revenue.

Overall, birds like the American Robin and European Starling cost the state of Oregon over $11 million in lost blueberry harvest last year.

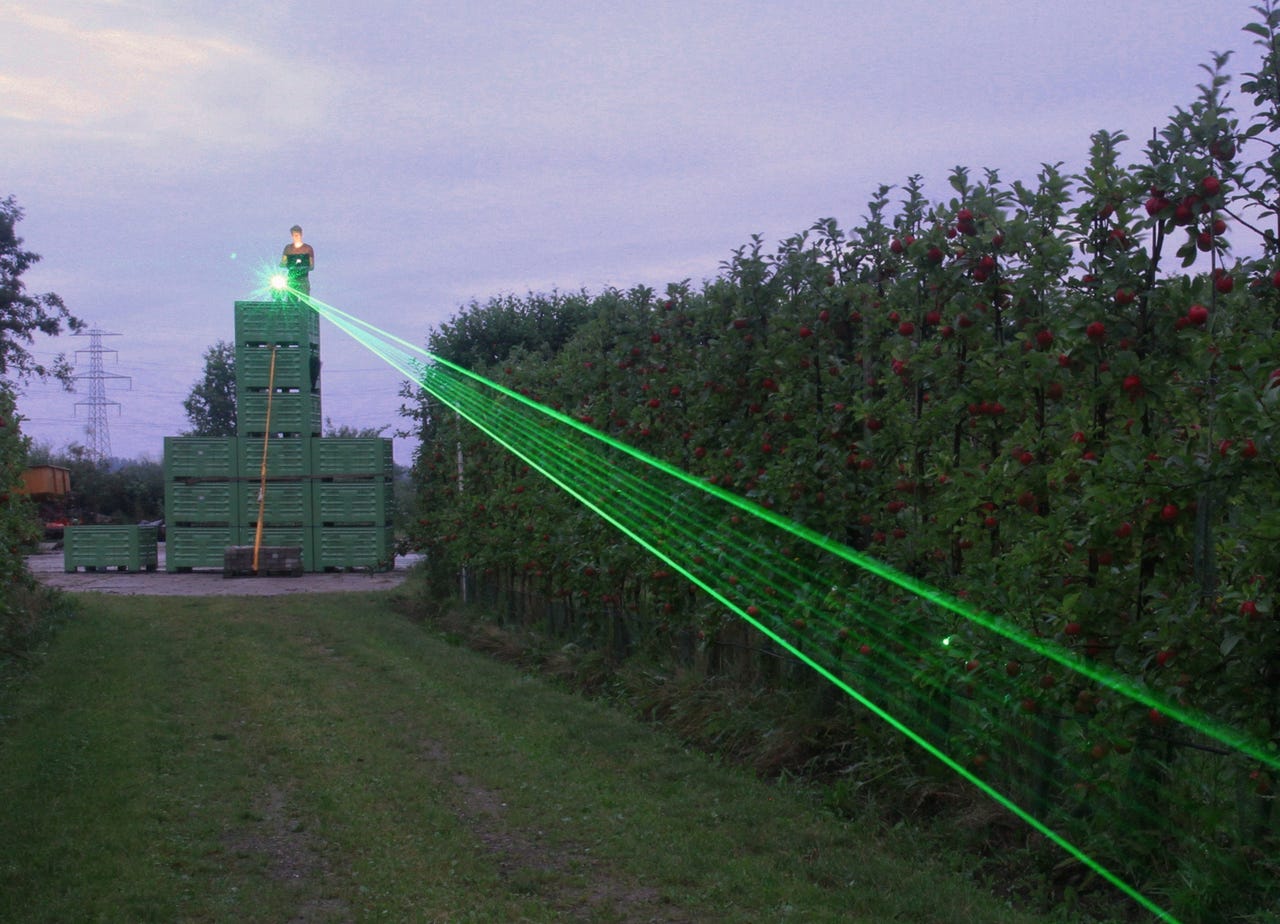

Using lasers to repel birds is a relatively new idea, but it's based on some interesting behavioral science. The laser bird deterrent technology takes advantage of a bird's natural instincts. Birds perceive an approaching laser beam as a predator and take flight to seek safety.

It's the same error your cat makes when he goes bonkers at the site of a little red laser.

The high-powered green lasers used in the deterrent system aren't meant to harm the birds, simply to stimulate the flight response.

Meduri Farms installed a system called the Agrilaser Autonomic made by the Dutch Bird Control Group. Six of the solar-powered systems were mounted on the periphery of the farm, cordoning off the blueberry crop.

The autonomous base keeps the lasers moving in a variety of patterns. Crucially, birds don't become habituated to the green dots, meaning there's no loss of effectiveness.

Because firing visible lasers indiscriminately is potentially hazardous to motorists, among other passersby, the Agrilaser system uses a projection safety system. If a laser strays outside a predetermined pattern field, the system will shut off.

It also avoids firing lasers overhead, where they can interfere with air traffic.

It's a high-tech solution to an age-old problem, and the latest example of how automation and connected device technology is helping farmers increase yields and efficiency.

Meduri, who installed his system last year, estimates his farm saves 578,713 pounds of blueberries annually thanks to the lasers.