After Aaron's Law reintroduced, new counter-bill aims to crack down on hackers

Congress is at odds on new cybersecurity legislation, with the introduction of two competing bills aimed at reforming computer misuse laws.

On Tuesday, Sens. Mark Kirk (R-IL) and Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) introduced two new bills -- one with the express aim at "punishing cyber criminals" who obtain information "without authorization."

The senators, who announced the draft Data Breach Notification and Punishing Cyber Criminals Act (you can read it below), want to increase maximum allowable fines and prison sentences for common cyber-crimes, including identity theft and obtaining information from a protected computer "without authorization."

And that is part of the problem. The bill doesn't fix what's fundamentally wrong with the law -- the outdated and overbroad definitions that lump in security researchers and those who simply violate a terms-of-service as malicious hackers.

"Current law does not sufficiently punish cyber criminals, and incidences like these recent devastating breaches of confidential information must be punished more aggressively," the senators wrote.

New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman applauded the bill as "long overdue."

The bill counters a bill reintroduced by Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-CA, 19th) and Sens. Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Rand Paul (R-KY), who last week launched an effort to "to better target serious criminals and curb overzealous prosecutions for non-malicious computer and Internet offenses."

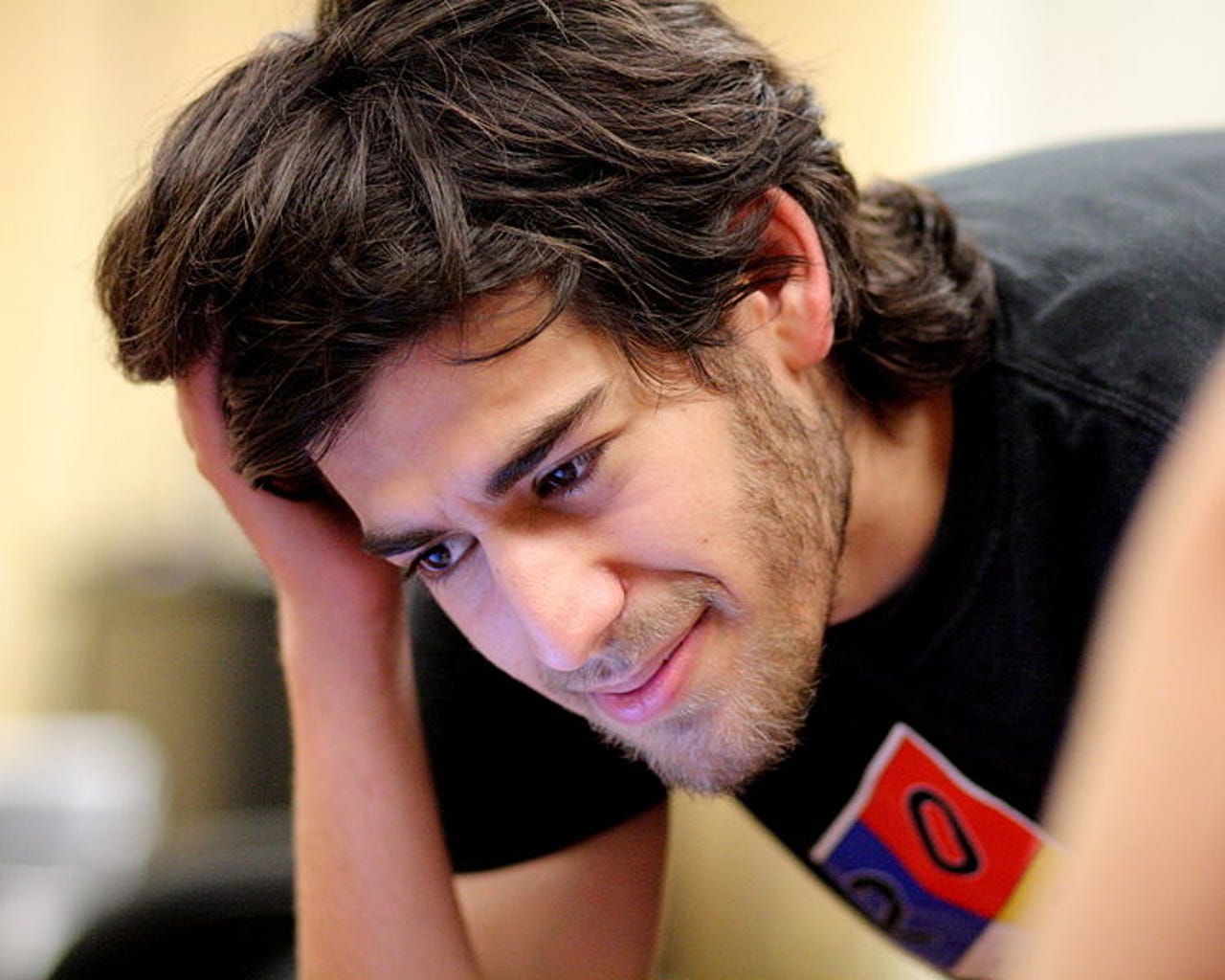

Their bill was "inspired" by Reddit co-founder, internet activist, and security researcher Aaron Swartz, who committed suicide after prosecutors said he would face 35 years in prison under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) for what prosecutors admitted was merely "an act of civil disobedience."

The reintroduced bill aims at reforming the CFAA to better reflect non-malicious Internet activities, such as breaking a site's terms of service or website notice.

In an opinion piece published by Wired in 2013, Lofgren and Wyden said their bill is about "refocusing the law away from common computer and Internet activity and toward damaging hacks." They added: "It establishes a clear line that's needed for the law to distinguish the difference between common online activities and harmful attacks."

Read more on ZDNET:

But the Kirk-Gillibrand bill doesn't reform the CFAA. It strengthens the punishments available to the government. The text of the bill is sufficiently vague enough to be misused and abused by prosecutors, who want to lay down a larger punishment against low-level crimes and acts of civil disobedience.

An aide for Kirk said the only matter in which the CFAA will be changed under the proposed bill is doubling the allowable fines and imprisonment for offences under CFAA. The aide said the bill does not change in any way the actual criminal offenses under CFAA.

And that's the problem.

Swartz's lawyer Jennifer Granick said in a blog post following her client's death that the notion of authorization is in the "eye of the beholder."

"Since every communication with a computer is access, the distinguishing line between legal and prison is the ephemeral concept of 'authorization'," said Granick.

She further argued that the CFAA gives "great power" to the owners of networks whose systems might be under attack. They are the ones who may "unilaterally decide what is right and wrong on their system," as well as the arbiter of whether or not a good-willed security researcher is a malicious hacker.

Had Aaron Swartz been alive today and prosecuted under the bill as though it was law, he would have faced an even greater fine and prison sentence for his "crimes" -- that is, attempting to make academic work, many created with public funding, freely available online.