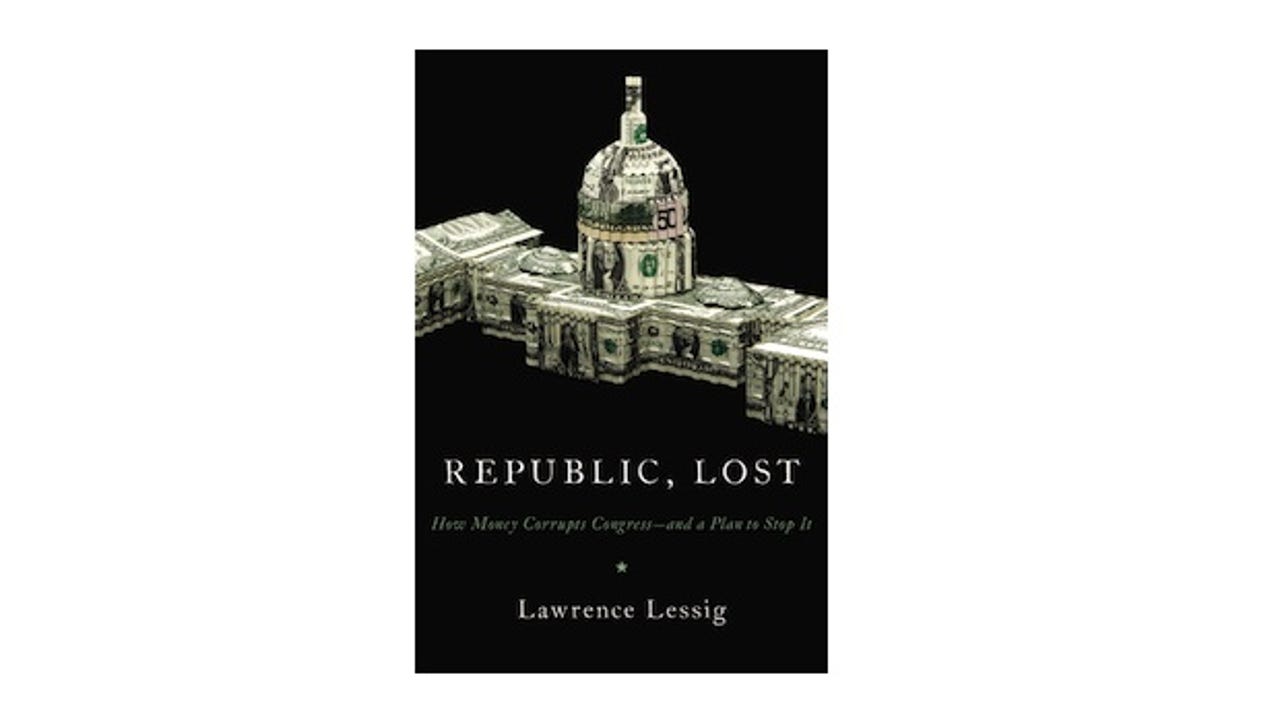

Book review: Republic, Lost

"Love makes the odds irrelevant," writes Lawrence Lessig at the end of Republic, Lost: How Money Corrupts Congress — and a Plan to Stop It. "It is a commitment to doing whatever can be done — sometimes destructively so — to beat the odds and save the soul who taught you that love."

This, he goes on to say, is why Americans should pick a strategy (if not one of the ones he proposes, then one of their own) to fight to retrieve the US's vanishing democracy. We can't just give up — not if saying we love our country means anything. The story starts with money…

I was 15 in 1969, when Joe McGinnis published his landmark book studying Richard Nixon's (as it turned out) successful bid for the Presidency, The Selling of the President 1968. That book uncovered the advent of a new style of politics: marketing, advertising, and, above all, television. This was the birth of image consultants and other political experts — and the beginnings of the need for vast sums of money to mount a campaign. A few years later, the 1972 movie The Candidate captured this new reality perfectly.

In Republic, Lost, Lessig does not cite McGinnis in tracing the way the US Congress has been corrupted without being criminally corrupt, but he could have: what presidents do one year, other politicians copy shortly afterwards. At any rate, Lessig is not in much disagreement about when the trouble started. In 1974, he writes, the aggregate amount spent by all candidates for Congress (House and Senate) was $56,000. In 1982 it was $343 million. By 2008 it was $1.8 billion. What happened? In one strand: the new marketing push McGinnis found. In the other, Lessig argues, the Republican discovery that, after the passage of Lyndon Johnson's civil rights legislation alienated some of the Democrats' traditional base, they had a fighting change to take control of Congress. Add experts and up the ante. Rinse thoroughly. Repeat, with more money.

Lessig spends the first half of the book laying out the consequences in detail, using examples such as climate change, the use of plastics in a baby's pacifier and agriculture subsidies. As the rest of the world should note (because how these US decisions are made affects everyone), Lessig finds that money determines not just what is decided but which topics are deemed important enough to warrant discussion. This is how ATM fees get more Congressional time than wars, and how high-fructose corn syrup is subsidised at the expense of sugar. Can Americans trust their government to make good decisions about health, safety, the financial markets or (Lessig's former specialty) copyright? Not while the need for campaign money is so desperate and so constant that politicians spend 30 to 70 percent of their time fund-raising.

Lessig makes it plain that he is not accusing Congress of accepting bribes for votes. No: instead, he is tracing the pernicious dependencies that foster the kind of personal relationships where everything is subtext and no outright deals need be made.

At the end of the book, Lessig suggests four strategies for reform: run distinguished candidates who are not politicians; allow only small donations; run candidates who campaign for funding reform and who quit when they get it; call a convention under Article V to change the Constitution. He calls these strategies "hopeless", and for the first three he's not wrong: the first is Michael Bloomberg, the second Howard Dean, the third — except for the quitting part — is Obama (Lessig is very clear about his disappointment in Obama, who was a university friend).

One idea he doesn't suggest is what the UK does: allow only three weeks for campaigning while keeping the exact date of the election somewhat uncertain. Sadly, this strategy — I envision a random number generator that decides how long any particular Congressman's term is going to be — probably wouldn't work in the US. They'd probably just campaign all the time, just in case. Like they already do now. But we can't just give up. What's a nation to do? Fight on, Lessig says.

Republic, Lost By Lawrence Lessig Hachette Book Group 383 pages ISBN: 978-0-446-57643-7 £20