ID cards holding back 21st century economy

No provision for online authentication in National Identity Scheme

Beyond privacy and 'Big Brother' concerns, the government's ID cards plan offers no basis for supporting a modern, online economy, says Andrew Watson from No2ID.

On 7 December 2009 the Prime Minister announced government plans "within the next five years, to shift the great majority of our large transactional services to become online only".

Even as he spoke, millions of taxpayers were completing web-based self-assessments. Online services are even more widely used in business, with online banking being perhaps the most prevalent.

However, as the online economy grows, so does the challenge of safely authenticating online transactions. Ironically, the main obstacle to progress in this area comes from a long-running government project to which Mr Brown has given his public support: the National Identity Scheme (NIS).

Today most of us rely on usernames and passwords to identify and authenticate ourselves online. It's a technique that's changed little since the dawn of time-sharing computing in the 1960s and is increasingly vulnerable to fraud. Banks alone lost an estimated £52.5m to online fraud in 2008, up 132 per cent from the previous year, according to the National Fraud Authority.

Some predict online fraud is growing more quickly than legitimate online commerce, and has already forced the permanent suspension of one online government service: HM Revenue and Customs' web-based child tax credit claim system permanently closed in 2005 after stolen personal details of 13,000 civil servants were used to defraud the department of an estimated £15m.

ID cards are damaging our online future, say campaigners

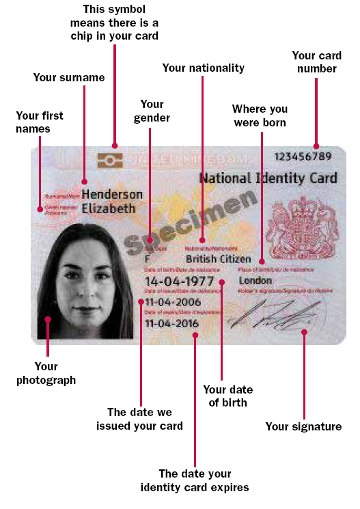

(Credit: Home Office)

We clearly need to devise better ways to establish online identities, and to authenticate that the people and organisations we communicate with are the legitimate users of those identities.

Unfortunately, the National Identity Scheme stands in the way. Despite the Home Office's claims it will become the country's "trusted and preferred provider of identity services", this huge, expensive, long-running project is doomed to fail, because it is not even attempting to support online authentication, let alone help modernise authentication technology.

The origins of this project date back to the creation of the wartime National Registration system in 1939. This population database, held on 7,000 transcript books at a requisitioned hotel in Southport, was designed to administer food rationing and military conscription. Everyone had an identity card bearing their name, address, signature and the all-important registration number that linked them to their official record in Southport.

Function creep inevitably set in, and by the early 1950s officialdom had devised dozens of new uses for the register, with identity cards frequently demanded so that the holders could be monitored and controlled via their official record.

Resentment about this increasing bureaucracy helped Winston Churchill win the 1951 General Election on a campaign promise to "set the people free", and the abolition of the scheme followed within months. . .

However, Whitehall did not forget the idea of national registration and identity cards, and repeatedly tried to reintroduce them. In 1974 then Home Secretary Roy Jenkins rejected them as a response to IRA terrorism. Later Peter Lilley, a minister from 1990 to 1997, noted that the idea had been "hawked round Whitehall for decades" but was merely a "solution looking for a problem".

Support for the idea re-emerged in 2002 when David Blunkett, then recently appointed as Home Secretary, announced legislation for a National Identity Scheme (NIS) aimed at creating a new "clean database" of the whole population.

Today the Home Office seems so obsessed with re-creating 1940s bureaucracy that it has ignored the arrival of the 21st century. Despite its apparent modernity, the scheme introduced by the Identity Cards Act 2006 is firmly rooted in a Victorian model of government.

Citizens cannot use it to identify themselves to each other or to businesses online, or even over the telephone. All the proposed uses for the scheme involve face-to-face transactions, such as collecting a parcel from a Post Office or going into a bank to transfer money between accounts.

So what about online commerce?

In 2003 a spokesman from online bank Smile.co.uk told the Guardian that "when it comes to internet banking, I don't think identity cards could help" - but to no avail.

In 2006 prominent banker Sir James Crosby was asked to produce an official report on how the proliferation of vulnerable identity assurance systems should be reformed to meet the needs of 21st century business. In the report he states the NIS "will not be the catalyst for the emergence of the consumer-driven universal ID assurance system envisaged by this report", and laid out 10 broad principles for future identification and authentication systems - all of which the NIS fails to implement.

By 2009 Colin Whittaker, head of security for UK banking body Apacs, said of the NIS: "Some of the features we were expecting in the ID card are not going to be present for the foreseeable future".

The NIS appears to be designed around a Home Office desire to hold data on the British population. There's no provision for identifying companies or other parts of government, nor for people and companies to authenticate themselves to each other. It only allows for people to identify themselves to the Home Office.

The only type of remote authentication provided, according to the Home Office is the collection of "security questions and answers" which "will only be used to enable a change of address or to report a lost or stolen identity card". Any changes to these core identity details would require a visit to a government office. Thus, far from facilitating the Prime Minister's vision of e-government, the NIS would in fact create new reasons for face-to-face interviews.

The National Identity Scheme is destined to fail. It's based on an antiquated concept of citizens identifying themselves to the state in face-to-face transactions, so far removed from the needs of business or government in the internet age that even if it isn't cancelled by politicians it is likely to fall into disuse and disrepute.

More importantly, until the NIS has been abolished, we can't move forward with deploying the robust, usable, decentralised, two-way electronic identification that we need for a 21st century economy.

Andrew Watson is a regional co-ordinator for the No2ID campaign.