Internet of Trash: The printable electronics you can just throw away

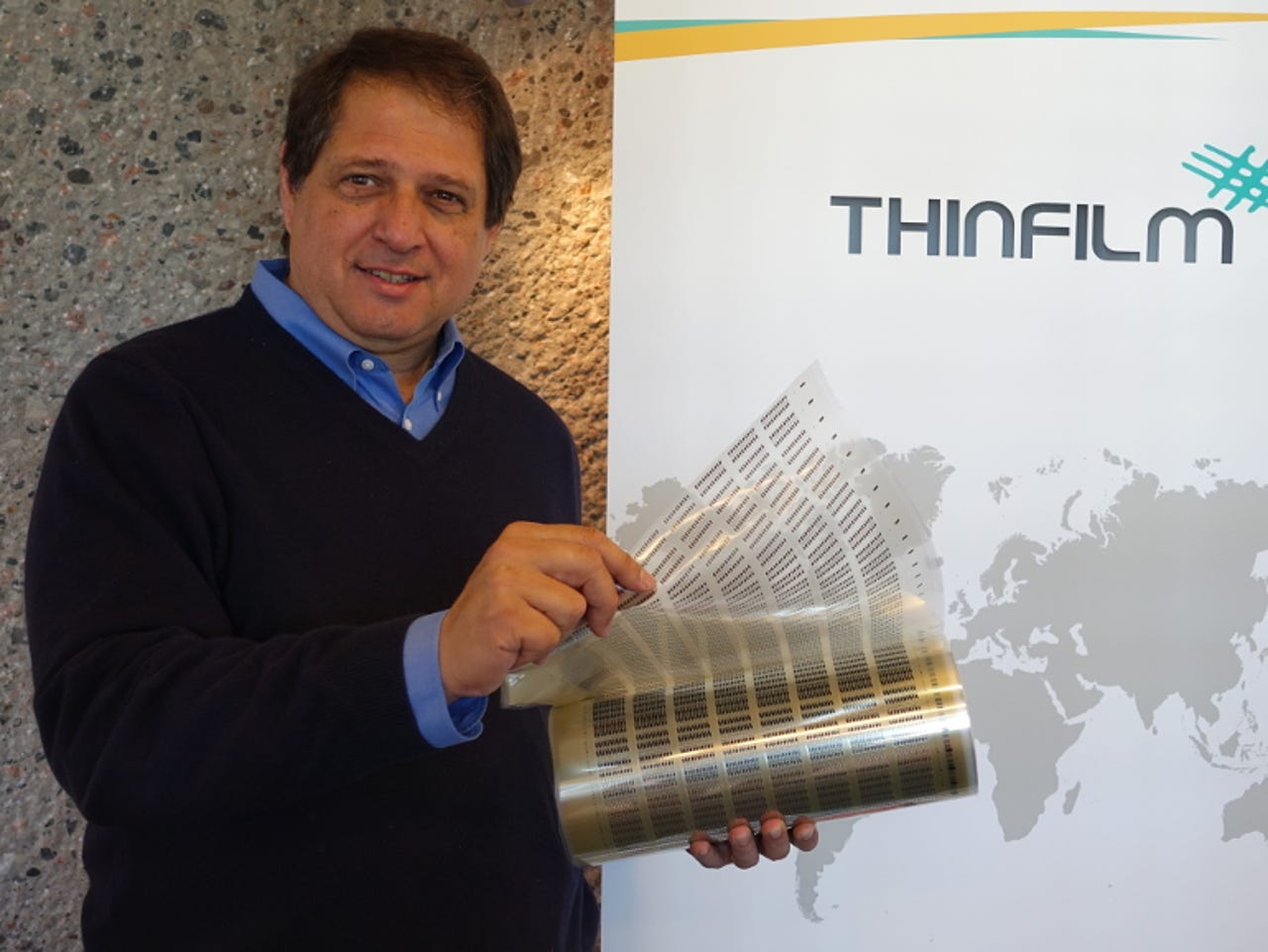

Thinfilm CEO Davor Sutija; "If you're going to integrate electronics into things that you throw away after use, you need to think on a larger scale than billions of units."

Norwegian-owned Thin Film Electronics, or Thinfilm, is in the business of printing electronics in massive volumes at a fraction of the cost of traditional silicon-based products.

Its offerings range from smart label sensors for food and perishable produce, to memory products for packaging, and near-field communication, or NFC, tags for applications in areas such as wine and spirits, and pharmaceuticals.

Last month, the company announced it has acquired a former Qualcomm-owned manufacturing facility in Silicon Valley to house a printed electronics production line, its US headquarters, and an NFC innovation center.

This facility will have the capacity to produce five billion units of the company's NFC OpenSense and NFC SpeedTap smart product label products per year, worth an estimated $680m in annual revenue.

"If you're going to integrate electronics into things that you throw away after use, you need to think on a larger scale than billions of units. You have to go to hundreds of billions of units. Some are even talking about a 'trillion-sensor roadmap'," Thinfilm CEO Davor Sutija tells ZDNet.

"You cannot print everything. We're working on the order of magnitude of a few thousand logical gates."

Today's processors contain up to two billion gates, but it hasn't always been so.

"Remember, the first microprocessor from Intel in 1971 contained 2,400 gates. Our NFC technology has 1,500 gates, whereas our temperature sensor has about 2,000. So, we're at the same level as Intel was in 1971," Sutija says.

He argues that the capacity does not exist in the world to make trillions of semiconductor-based chips. At current levels of production, about 20 billion silicon-based microcontrollers are produced yearly.

"Perhaps it sounds strange to make all that effort for something Intel did 45 years ago. But the reason is that the number of silicon semiconductors manufactured is limited."

Considering the ambition of equipping consumer goods and other mass-market products with a bare minimum of intelligence, Sutija believes semiconductors won't be able cover that need, given the volumes involved.

"Xerox have licensed our memory technology, so we've taught Xerox how to print memory. They've said Xerox Printed Memory will become a technology pillar for Xerox in the future, and this is developed here in Scandinavia," Sutija says.

However, the facility in California will focus on the company's NFC products, printing kilometer-long rolls of NFC labels. This circuitry can have several functions.

"We can build an NFC unit that contains one or two separate codes, or a very simple sensor that can measure if it's been too cold or warm, with precision. We can't store very much data, so they've got to be simple sensors, showing if a light is on or off, if the fish has been cool enough during transport, and so on," Sutija says.

When combined with an NFC-equipped smartphone and a companion app, the labels have several uses. They can prove the authenticity of a medical or luxury product, or when integrated into the seals on packaging, they can show the product is unopened. The functionality can also extend to improve direct communication between vendor and customer, both before and after purchase.

Sutija is clear that the products his company is offering are not very advanced, measured by semiconductor standards.

"We're trying to solve tasks that are obviously solvable with semiconductors. But we can do it in a way that makes it scalable and cheap enough to be used in billions of places. If you need processing power, you'll use semiconductors. But if you have simple tasks for billions of cases, you can use printed electronics," he says.

Sutija is particularly enthusiastic about the opportunity created by more and more smartphones employing NFC comms technology.

"In 2018 there will be two billion smartphones with NFC, and in that context, five billion labels are a drop in the ocean. Therefore, there may be more interested parties like Xerox who want to license our technology, and we're pleased with that," Sutija says.

"We want to end up as a licensing company, like ARM. I talked with ARM a couple of years ago. They said that what we're doing now, is exactly what ARM did 10 years ago."