Microsoft's Hyper-V: why all the fuss?

In the field of server virtualisation, the current focus of attention is the impending release of Hyper-V, Microsoft's long awaited hypervisor technology (due to ship six months after the launch of Windows Server 2008). But what exactly is a hypervisor? More importantly, why is Microsoft's implementation causing such a stir, and how will Hyper-V fit into the increasingly competitive server virtualisation market?

Hypervisor theory

Like original offerings from market pioneer VMware and others, Microsoft's current server virtualisation product, Virtual Server 2005, is a hosted solution, designed to run as an application on top of a standard operating system. In Microsoft's case that means Windows Server 2003, the Virtual Server software sharing out the server's processors, memory, disk, network and other I/O interfaces between multiple virtual machines (VMs) via the host OS.

A hypervisor changes all that, removing the need for a host operating system. At least, there's no host OS in a format most of us would recognise; however, to save having to reinvent the wheel, most implementations borrow quite a bit from either Linux, Unix or Windows. That said, a hypervisor can still be installed directly onto a bare server, enabling it to communicate directly with the supporting hardware rather than via an intervening OS.

This approach is designed to deliver a number of potential benefits, the first of which is enhanced performance. This is made possible because an ordinary operating system has to do a lot of other work besides looking after guest VMs. This includes tasks such as file and printer sharing, and hosting services, applications and so on. A hypervisor, on the other hand, can be optimised purely for the task of running virtual machines. The end result is, typically, the ability to host more virtual machines on the same hardware and/or improve their level of performance.

Second, although a hypervisor does little to enhance security at the individual virtual machine levels, there should be far fewer vulnerabilities in the underlying hypervisor code compared to a standard host OS, making for a much more secure solution overall.

And third, cost reduction is yet another possible benefit, as there's no need to licence a host OS before virtual machines can be deployed. However, this really only applies to Windows implementations and, even then, it isn't a major issue.

Of course there are also disadvantages with hypervisors. For example, they are much more hardware-specific than hosted virtualisation products. Even so, hypervisors are generally seen as a good thing and a number of established products are already available — most notably, VMware's market leading ESX Server plus various implementations of the open-source Xen hypervisor from the likes of Red Hat, Novell and, since its acquisition of XenSource, Citrix.

How Hyper-V stacks up

Microsoft's Hyper-V differs significantly from most existing hypervisor products. To begin with, the latter all tend to be based on Linux/Unix code, whereas Microsoft's hypervisor (originally codenamed Viridian before being rechristened) is tightly bound up with its new server operating system, Windows Server 2008. But there are other differences too.

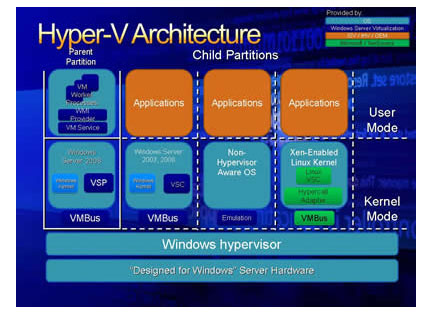

For example, although Hyper-V is installed directly onto server hardware, enabling it to host multiple virtual machines in logically separate 'partitions', the primary or 'parent' partition has to run Windows Server 2008. This may sound contrary to the hypervisor ethos, but isn't really. Rather, Hyper-V takes advantage of drivers and services within the Windows software to both better communicate with the supporting hardware and to provide for management. Microsoft describes this as a 'micro-kernelised' architecture, enabling it to minimise the footprint of the core Hyper-V code while still delivering a rich set of features.

With Microsoft's Hyper-V, Windows Server 2008 (or a subset of it) must be running in the parent partition.

Despite its dependence on Windows, it's also important to understand that you don't need the full server OS for Hyper-V to work. The full product can be run in the parent partition if you want, and Windows Server 2008 purchased with the virtualisation component to enable this to happen. However, the cut-down command-line Server Core implementation, which lacks the Windows GUI, can be employed instead. Microsoft has also announced a custom Hyper-V Server product complete with enough Windows Server code to support the hypervisor but nothing else. This is expected by the end of the year and will sell for just $28 per host — effectively giving it away.

Another key differentiator with Hyper-V is the ability to augment the standard I/O emulators used by most other virtualisation products with technology that's better able to use the underlying hypervisor. This involves the use of so called Virtualization Service Providers (VSPs), which provide a shared interface to drivers in the parent partition and Virtualisation Service Clients (VSCs) in child (guest) partitions. The two then communicate via a Virtual Memory bus (VMBUS), giving guests direct access to the host drivers with no need for the extra translation processing required of I/O emulators.

VSPs (Virtual Service Providers) and VSCs (Virtual Service Clients) provide access to drivers in parent and child partitions respectively. 'Enlightened' guest OSs come with the required VSC code, while non-enlightened platforms must make do with emulation.

Of course, for this to be possible, guest virtual machines need to be equipped with the necessary VSC code — so-called 'enlightened' operating systems. In fact, this is not absolutely essential because non-enlightened guests can still use emulation. However, enlightened platforms are better equipped to use the host resources, with knock-on effects in terms of performance and flexibility.

Windows Server 2008, naturally, is an enlightened OS, as is Windows Vista. Microsoft can also provide enlightened extensions for Windows XP and Windows Server 2003, but is mostly leaving it up to third parties to cater for other platforms. XenSource (now Citrix) is the most advanced, having collaborated with Microsoft on the Hyper-V development. However, others aren't far behind: there's wide support for the beta implementation already, with more expected from companies like Novell and Red Hat by the time the Microsoft platform finally ships.

Hyper-V realities

Hyper-V is a key technology for Microsoft, and the company is throwing a lot of resources behind the development of what it hopes will become the preferred server virtualisation platform in enterprise datacentres. However, there are a few issues to bear in mind, some minor some less so.

Although the software can only be installed on servers with 64-bit processors, that's not too big a drawback: no self-respecting corporate will buy anything less, and 32-bit servers are as rare as hen's teeth anyway. Moreover, unlike Virtual Server 2005, Microsoft's hypervisor can host 64-bit as well as 32-bit guests, which means it can be used to run more demanding applications such as the latest 64-bit-only Exchange Server 2007.

Hyper-V also requires processors with either Intel VT or AMD-V hardware virtualisation extensions — although, again, that's now very much a standard hardware feature.

On the plus side, Hyper-V is a lot more scalable than Virtual Server 2005, which is unlikely to be developed much further, according to Microsoft Server product manager Gareth Hall. This is understandable because Virtual Server 2005 is limited to 32-bit virtual machines with a single virtual processor per VM. By contrast, Hyper-V, even in its first release, can run either 32-bit or 64-bit guests with up to 4-way virtual SMP. Each Hyper-V guest can also have up to 64GB of memory, compared to just 3.6GB with Virtual Server 2005.

Indeed, the capabilities of Hyper-V come close to matching what's possible with VMware's ESX Server and catapult Microsoft straight into the top echelon of server virtualisation vendors. Of some concern, however, are the delays the company has encountered getting the product to market, together with compromises in terms of functionality that have been made to meet release dates.

Originally expected to be available along with the rest of Windows Server 2008, Hyper-V development has been dogged by problems. The official line is that it will now be a no-cost upgrade, available 'within 180 days of Windows Server 2008 being released to manufacturing'. The RTM date was 4 February so, according to that claim, Hyper-V ought to ship on or around 1 August. Although that's not too far away, it's still well behind both VMware and Xen.

Functionality has also been cut back since the original announcement, the most significant omission being the ability to migrate virtual machines from one host to another without shutting them down. This option is available both with VMware ESX Server and, more recently, XenServer Enterprise from Citrix. Microsoft is working on something similar that can take advantage of the enhanced clustering facilities in Windows Server 2008. However, it has yet to provide a firm date for when this will be introduced.

Fitting into the virtual landscape

As a late entrant to the hypervisor market, Microsoft faces a huge task if it expects to be able to oust VMware from its leading position. That doesn't mean it can't happen, of course. Hyper-V will benefit from being bundled as part of Windows Server 2008, and the market for server virtualisation is far from saturated. In fact, Microsoft reckons that less than 10 per cent of production servers are deployed this way. The company also has another trick up its sleeve, in the form of its VM management tools.

As with Virtual Server 2005, tools to manage individual Hyper-V deployments are included with the core software. But Microsoft has also recently added a Virtual Machine Manager (VMM) product to its System Center family, which can centrally manage virtual machines across multiple servers running both virtualisation platforms.

However, the ability to manage Hyper-V won't be added until shortly after the hypervisor is released. In the meantime, Virtual Machine Manager 2007 is limited to managing Virtual Server 2005, with VM interoperability between the two platforms allowing customers to start off with Virtual Server now and quickly upgrade when Hyper-V ships.

According to Microsoft, the next release of VMM will be able to manage VMWare virtual machines as well, with Citrix XenServer support to follow shortly thereafter. That's a wise move given general agreement that server virtualisation is unlikely to last very long as a separate application. To this end, Citrix has stated its intention to provide compete interoperability between its product and Hyper-V and the consensus is that hypervisors will, eventually, be embedded into server hardware. Indeed, Dell has already started down this route by offering XenServer, and soon Hyper-V Server, as a factory-fit option on its PowerEdge systems.

When that happens, customers will no longer be concerned about the technology involved or who it belongs to. Rather, the key differentiator, and the product that most organisations will buy, will be tools to manage virtual machines. That's already starting to happen and it's here, in the management tools rather than the underlying technology, that Microsoft looks to set to make its real mark on the server virtualisation landscape.