Samsung v. Apple: A Supreme Court case over "winner takes all"

After a years-long legal battle, Samsung last year agreed to pay more than half a billion dollars to Apple for infringing on various iPhone patents. However, the case isn't over -- if the arguments before the Supreme Court on Tuesday go Samsung's way, the Korean manufacturer could get back a large chunk of its money.

More broadly, the eight justices on the court could deliver some significant opinions regarding the value of product design. Those opinions could impact the way businesses in the tech industry and other sectors move forward with design patents -- and potentially the ferocity of patent trolls.

What's the case about?

Back in 2012, a jury ruled that Samsung's phones infringed upon Apple's design and utility patents. Tuesday's case focuses on three design patents that covered a black rectangular front face with rounded corners, a front face with a bezel on the surrounding rim, and the iPhone interface's grid of 16 icons. Citing the Patent Act, the lower court said Samsung was obligated to pay Apple all of the profits it earned from smartphones using those designs.

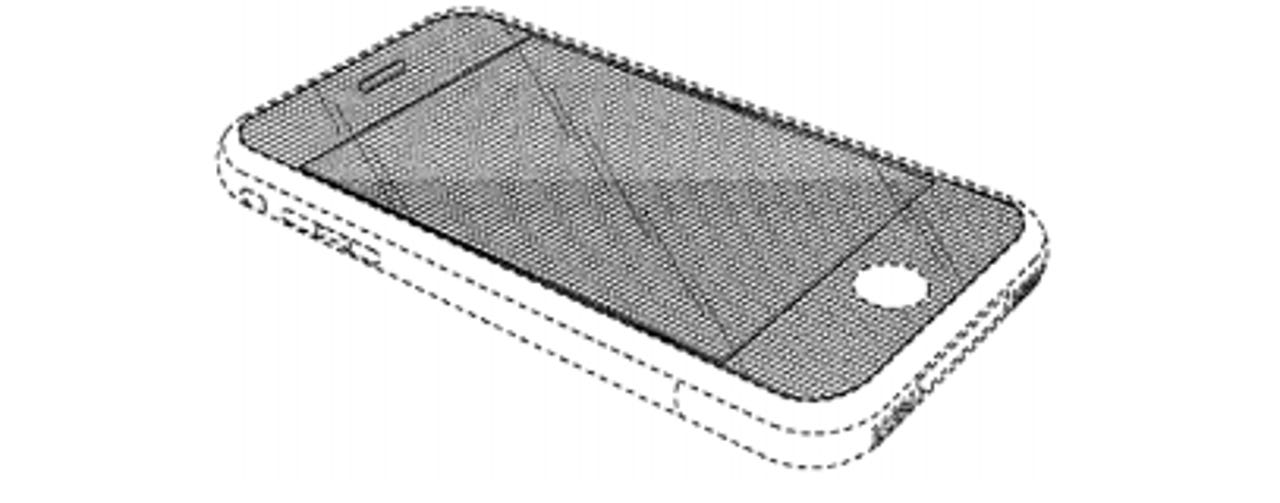

Using solid lines for the claimed subject matter and broken lines for disclaimed features, Apple's D618,677 ("D'677") patent shows a black rectangular front face with rounded corners.

Apple was originally granted more than $1 billion in damages, but that sum was later reduced. Samsung appealed to the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals, but that court sided with Apple.

Security

Now, as ZDNet's Steven J. Vaughan-Nichols noted earlier this year, Samsung is arguing before the Supreme Court that it should get back the $399 million in damages it paid to Apple for infringing on those design patents. Samsung argues the damages should be limited to the profits it made from the specific components of its phone that relied on Apple's patents -- not all of the profits from its smartphones.

The case hinges on a key portion of the Patent Act, which says that any person who uses a patented design "to any article of manufacture" is "liable... to the extent of his total profit." Samsung has argued it would be "ridiculous" to give Apple all of the profits from smartphones "which contain countless other features that give them remarkable functionality wholly unrelated to their design. By combining a cellphone and a computer, a smartphone is a miniature internet browser, digital camera, video recorder, GPS navigator, music player, game station, word processor, movie player and much more."

The Supreme Court, Samsung argues, should reverse the Federal Circuit Court's decision because that court never gave the company the chance to argue that its phones' screens and interfaces were the only relevant "articles of manufacture" -- not the entirety of the phones.

Apple, for its part, argues, that "the iPhone's explosive success was due in no small part to its innovative design, which included a distinctive front face and a colorful graphical user interface -- features protected by U.S. design patents."

The Cupertino company argues the terms "articles of manufacture" and "total profit" are clear cut and that Samsung could not prove otherwise to the lower courts.

Who sides with Apple?

Since the Supreme Court agreed in March to the hear the case, it's received several amicus briefs from other major companies, industry groups, and academics lining up on each side.

Apple has the support of brands heavily invested in their designs, such as Adidas and Tiffany, as well as groups that protect them. The American Intellectual Property Law Association filed an amicus brief telling the court, "It bears emphasis that many of the run-of-the-mill design patent cases are about counterfeiting, which remains a major problem."

A brief signed by 113 industrial design professionals and educators argues that the visual design of a product is critically linked to its functionality.

"This is especially true in the market for complex technological products," the brief says. "Counterintuitively, when a single product performs numerous complex functions, and when parity in functionality is assumed across manufacturers, product design becomes more important, not less. By stealing designs, manufacturers steal not only the visual design of the product, but the underlying functional attributes attached to the design of the product, the mental model that the consumer has constructed to understand the product, and the brand itself and all associated attributes developed at great expense in the marketplace."

Who sides with Samsung?

Samsung, meanwhile, has the backing of public advocacy groups Public Knowledge and the Electronic Frontier Foundation; industry groups like the Computer and Communications Industry Association (CCIA); and several major tech companies including Dell, eBay, Facebook, Google, Motorola, Red Hat, and HP.

The lower court's interpretation of the Patent Act in this case would "transform a design patent into a sort of super-utility patent," the CCIA argues, giving design patents far too much weight.

"The sheer number of potential design patents that could apply to a single smartphone exposes manufacturers to grossly unjust liability," the brief adds. "For example, Apple has about 200 active design patents entitled 'Electronic device.' If Samsung were sued on each of those patents by separate entities, Samsung's potential damages would be many billions of dollars."

Meanwhile, the individual businesses siding with Samsung signed onto a brief that argued the Federal Circuit's position would aggravate the already-inevitable problem of increased design patent litigation. Litigation is already sure to increase, given that design patents are being granted at a "record clip," it says, citing the Patent and Trademark Office's annual reports: Of the approximately 750,000 design patents that have been granted in American history, more than half have been granted in the last two decades.

"While fewer design patents are litigated than utility patents, the filing of design-patent cases has shown no sign of slowing down," they warn. "This Court has recognized that the activities of 'patent trolls' 'can impose a harmful tax on innovation.'"

While the court could hand down an impactful decision, it could also evade the major question of the value of design patents. Instead, the court could remand the case to the Federal Circuit to reconsider a less inclusive definition of "article of manufacture."

In the meantime, it's been hard to tell what impact the ongoing court battle has had on the market, if any. Samsung and other manufacturers continue to roll out new versions of smartphones using similar designs, seemingly undeterred by Samsung's court setbacks. At the same time, Apple continues to bring in boatloads of cash thanks to the iPhone, even as similar-looking smartphones proliferate.