Business

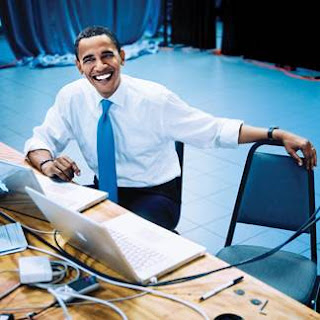

The many impediments to digital White House

Obama might want to bring the federal government into the Web 2.0 age, but there are deeply entrenched impediments to doing that. Changing Washington's tech culture would mean changing Watergate-era laws and issuing numerous changes to bureaucratic regulations.

Wired Mag has a great article asking just how wired the Obama White House will be. The answer? Probably not as wired as he or we would like.

The reasons? The campaign was a well-heeled, highly disciplined startup operation that knew how to get things done cheap or free. The federal bureaucracy is a slow-moving, technologically backward multi-headed hydra. Think Flickr joining Yahoo. Or AOL "acquiring" Time Warner. Whose culture really changes?

Some of the impediments:

- The huge size of the government.

The federal government operates more than 24,000 separate sites, many of them years out of date. "Nobody stepped back and asked strategically, how do we do this?" [the General Services Administration's Bev] Godwin says. "Whenever there is a new initiative or program, they put up a new Web site." And the first thing they usually do on that site, she says, is post a bandwidth-hogging picture of the bureaucrat in charge.

- Post-Watergate regulations.

Amendments to the 1973 Rehabilitation Act, for example, require that all government Web content be made reasonably accessible—in real time—to disabled users. Also, six months of negotiations between the General Services Administration and Google to establish a federal YouTube channel have stalled over similarly intricate legal issues. Meanwhile, a Clinton-era law called the Paperwork Reduction Act requires that an agency undergo a laborious approval process any time it "surveys" more than 10 people. The result: "Agencies tend to avoid doing these kind of surveys," Godwin says. Would having users submit information to a social network or wiki count as a survey? Nobody knows.

- Procurement insanity.

Instead of building [FedSpending.org] in-house, the Office of Management and Budget decided to license something similar from a nonprofit watchdog group, OMB Watch—for just 4 percent of what the government had expected to spend. It was a striking victory for government efficiency, but the process behind the scenes "was extremely difficult," says Gary Bass, executive director of OMB Watch. After floating the idea of donating the system to OMB ("the government can't take things for free," Bass quickly learned), the nonprofit had to sign on as a subcontractor and undergo three rounds, and six wasted months, of bidding before the deal was complete.

- Privacy concerns and online noise

[In Massachusetts, the Patrick] administration was immediately blasted when a database feature designed to verify Massachusetts residency was alleged (incorrectly) to reveal unlisted phone numbers. The privacy flap lured a collection of trolls and conspiracy theorists to the site, crowding out earnest discussion on gambling bills and income taxes with 9/11 chatter and religious debates.

Even if all these – and other – problems are overcome, what are the goals of a digital presidency? It's not, Wired writer Evan Ratliff says, that online commenters should guide policy but rather that the American people should feel listened to.

Instead of turning WhiteHouse.gov into a governmental synthesis of Facebook and Wikipedia, or running a permanent campaign off the White House email list, Obama's best shot at rebooting the government is to remember how he got there: making people feel that they were part of the solution and then enabling them to talk to one another and take action.