How tech companies use warrant canaries to secretly communicate with you

Picture this. An unnamed technology giant in Silicon Valley is handed a top-secret data demand to turn over data on one customer (or potentially all of them).

Because the order is classified, the company isn't allowed to tell anyone, let alone the customer in question.

Unless someone leaks the order -- which would almost inevitably lead to jail time -- nobody will ever know. Companies aren't even allowed to disclose it in their transparency reports, a popular way of disclosing how many law enforcement requests are made in a particular time frame.

But in the wake of the Snowden leaks, where allegations of complicity in surveillance activities were made, companies realize customer trust is more important than ever.

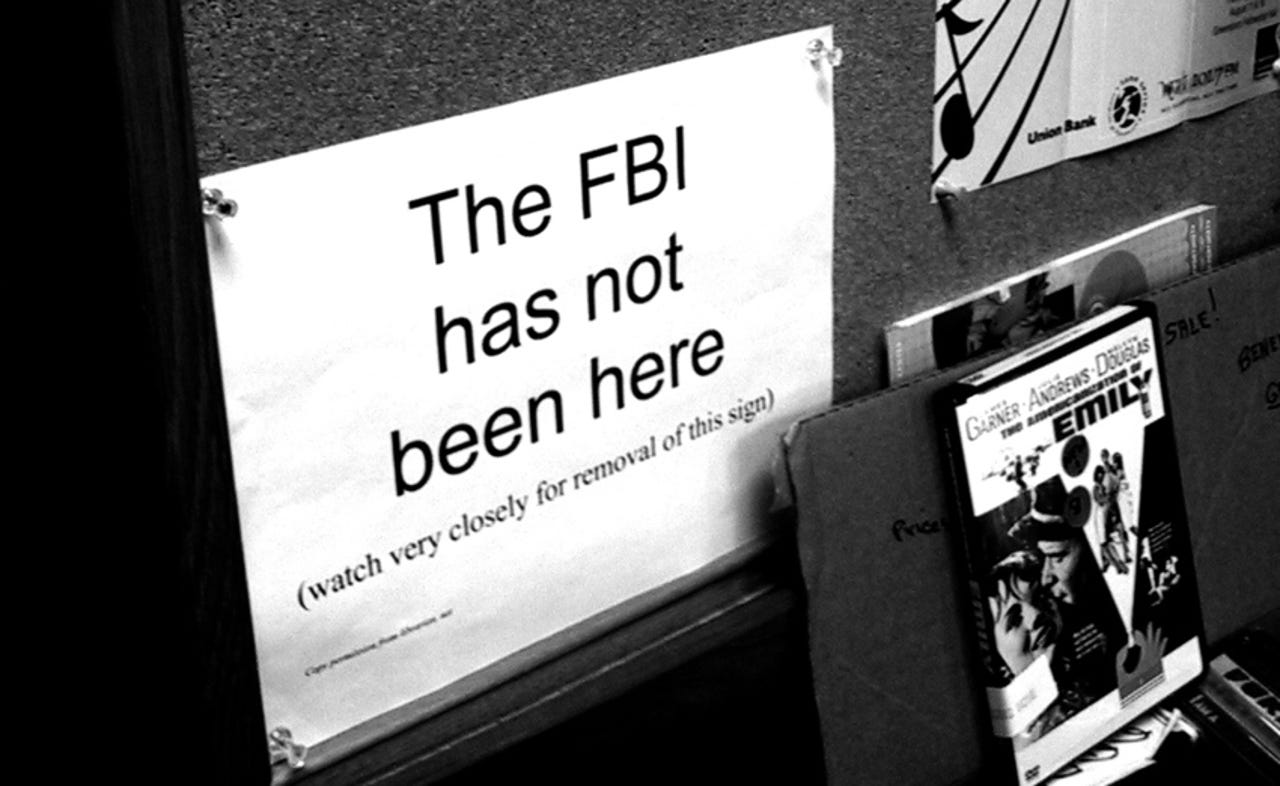

Many are turning to the "warrant canary," which is a public statement on a website that asserts that a top-secret data demand has not been received, published in anticipation of receiving such an order. Removing the notice suggests one has been received but doesn't violate the gag order because nothing was explicitly said. Vermont-based librarian Jessamyn West popularized the warrant canary by posting signs saying, "The FBI has not been here."

But the legality of warrant canaries was called into question by one leading security researcher last year.

Moxie Marlinspike, pseudonym of a co-founder of Whisper Systems said in a Github post last year that he believed removing a warrant canary would "likely have the same legal consequences as simply posting something that explicitly says you've received something."

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) said there's no law in effect to prevent warrant canaries from being used.

The privacy group's latest project, dubbed "Canary Watch" and launched last month, lists warrant canaries and monitors any changes to them.

"No court has ever publicly addressed the issue," said EFF staff attorney Mark Rumold in an email. It would be "unprecedented," he said, for the government to force a company to keep that warrant canary in place. "I'm skeptical it would ever happen," he added.

Rumold said there may be "risks" associated with warrant canaries, but until a court rules against them the EFF will carry on supporting organizations using them.

But many technology companies haven't followed suit because they can't. That's because they have been (and continue to be) subject to a gag order. One prominent example is Verizon, which was forced to comply with a Section 215 order for phone records data of every one of its customers.

Apple became the first high profile Silicon Valley technology giant to include a warrant canary in its transparency reports in 2013, but it was later removed for unspecified reasons. (It's still not clear if Apple had been hit with a gag order -- or a warrant request.)

Warrant canaries fall in a legal gray area, untested in the courts. In response to the Snowden leaks, tech companies wanted to be more transparent -- partly to exonerate them from any alleged complicity in the NSA's surveillance activities.

Internet of Things

But the government doesn't make it easy. The Justice Department allows companies to disclose the number of secret data demands in ranges. The lowest range is zero to 999 requests. That means companies that haven't received a request are lumped in with those who have.

Rachel Levinson-Waldman, counsel at the Liberty and National Security Program at New York University's Law School, argued that companies choosing to disclose the zero figure can't be gagged on a non-existent request.

"I think the companies are on decently strong ground, understanding that this is a complex area," she said.

Twitter is in the middle of a legal fight with the Justice Department after it filed a lawsuit aiming to settle whether or not warrant canaries are protected under the First Amendment right to free speech.

The Justice Department sought to dismiss most of the claims. Levinson-Waldman said "courts are starting to look more critically at government assertions of national security interests" in the wake of the Snowden leaks, which may mean the courts will rule in Twitter's favor.

Oral arguments are set to begin later this month.