What Microsoft won't tell you about Windows 7 licensing

Microsoft offers many ways to buy Windows 7. You can buy the operating system preinstalled on a new PC, upgrade an existing PC using a shrink-wrapped retail package, purchase an upgrade online, or build a PC from scratch and install Windows yourself. In each of these cases, you can also take your pick of multiple Windows editions The price you pay will vary, depending on the edition and the sales channel. There are different license agreements associated with each such combination. Those license agreements are contracts that give you specific rights and also include specific limitations.

This might sound arbitrary. Indeed, a common complaint I hear is that Microsoft should simply sell one version of its OS at one price to every customer. That ignores the reality of multiple sales channels, and the fact that some people want the option to pay a lower price if they don't plan to use some features and are willing to pay a higher price for features like BitLocker file encryption.

If you're not a lawyer, the subject of Windows licensing can be overwhelmingly confusing. The good news is that for most circumstances you are likely to encounter as a consumer or small business buyer, the licensing rules are fairly simple and controversy never arises. But for IT pros, enthusiasts, and large enterprises knowing these rules can save a lot of money and prevent legal hassles.

I have been studying the topic of Windows licensing for many years. As I have discovered, Microsoft does not have all of this information organized in one convenient location. Much of it, in fact, is buried in long, dry license agreements and on sites that are available only to partners. I couldn't find this information in one convenient place, so I decided to do the job myself. I gathered details from many public and private sources and summarized the various types of Windows 7 license agreements available to consumers and business customers. Note that this table and the accompanying descriptions deliberately exclude a small number of license types: for example, I have omitted academic and government licenses, as well as those provided as part of MSDN and TechNet subscriptions and those included with Action Pack subscriptions for Microsoft partners. With those exceptions, I believe this list includes every license situation that the overwhelming majority of Windows customers will encounter in the real world.

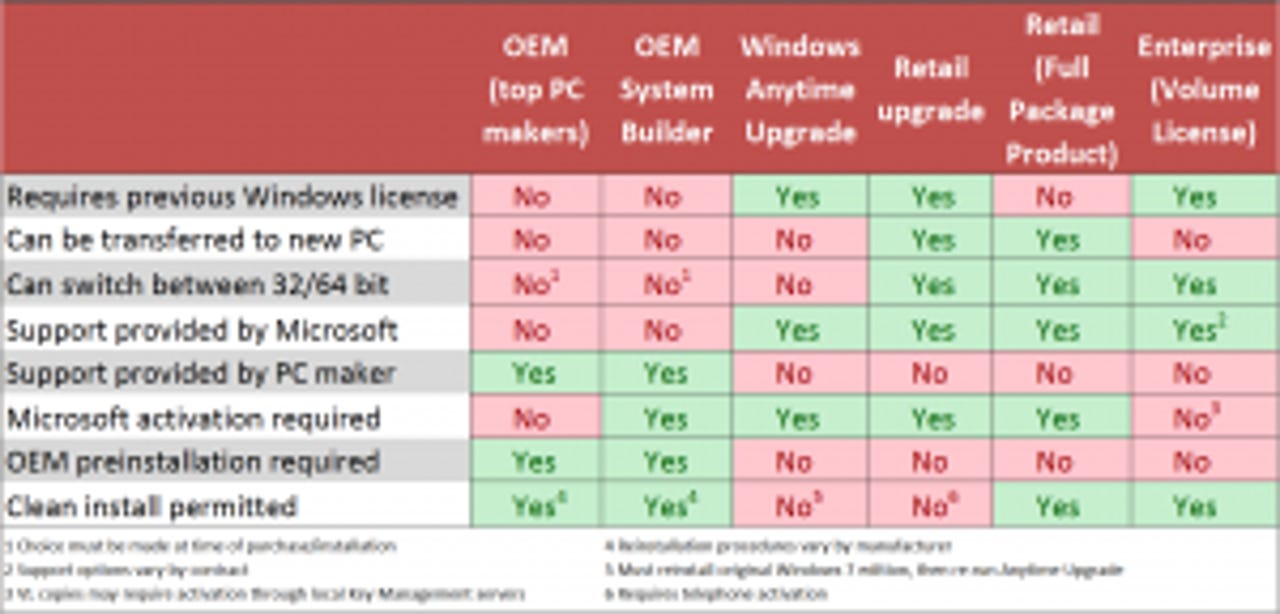

The table below is your starting point. The license types listed in the columns of this table are arranged in rough order of price, from least expensive to most expensive. For a detailed discussion of each license type, see the following pages, which explain some of the subtleties and exceptions to these rules. And a final, very important note: I am not a lawyer. This post is not legal advice. I have provided an important disclaimer on the final page of this post. Please read it.

[Click image to open full size in its own window]

Although the table above is packed with information, it's not the whole story. Please click through to the following pages for detailed explanations.

Windows 7 OEM versions

According to Microsoft, roughly 90% of all copies of Windows are purchased with new PCs, preinstalled by Original Equipment Manufacturers that build the PC and sell Windows as part of the package. That will certainly be true with Windows 7.

OEM (major PC manufacturer) This is, by far, the cheapest way to purchase Windows 7. The top 20 or so PC makers (sometimes called "royalty OEMs") collectively sell millions of PCs per month with Windows already installed on them. When you start up that PC for the first time, you accept two license agreements, one with the manufacturer and one with Microsoft. Here's what you need to know about this type of license agreement:

- Your Windows license agreement is between you and the PC maker, not between you and Microsoft.

- The OEM uses special imaging tools to install Windows on PCs they manufacture. When you first turn on the PC, you accept a license agreement with the OEM and with Microsoft.

- The PC maker is required to provide support for Windows. Except for security issues, Microsoft will not provide free support for any issues you have with Windows purchased from an OEM.

- Your copy of Windows is locked to the PC on which you purchased it. You cannot transfer that license to another PC.

- You can upgrade any components or peripherals on your PC and keep your license intact. You can replace the motherboard with an identical model or an equivalent model from the OEM if it fails. However, if you personally replace or upgrade the motherboard, your OEM Windows license is null and void.

- Windows activation is typically not required when Windows is preinstalled by a royalty OEM. Instead, these copies are pre-activated at the factory. Your copy of Windows will be automatically reactivated if you reinstall it using the media or recovery partition from the PC maker, it will not require activation.

- At the time you purchase an OEM copy of Windows 7 to be preinstalled on a new PC, you must choose either 32-bit or 64-bit Windows. Your agreement with the OEM determines whether you can switch to a different version; some PC makers support only a single version with specific PC models and will not allow you to switch from 32-bit to 64-bit (or vice versa) after purchase.

OEM (System Builder) If you buy a new computer from a local PC builder (sometimes called a "white box" PC), you can get an OEM edition of Windows preinstalled. This type of OEM license differs in a few crucial details from the version the big PC makers sell:

- As with the royalty OEM versions, your copy of Windows is locked to the PC on which it is installed and cannot be transferred to a PC, nor can the motherboard be upgraded.

- Under the terms of its agreement with Microsoft, the OEM must use the Windows OEM Preinstallation Kit (OPK) to install Windows. When you first turn on the PC, you accept a license agreement with the OEM and with Microsoft. The OEM is required to provide support for your copy of Windows.

- Activation of your new PC is required within 30 days. The product key should already have been entered as part of the OPK installation and activation should be automatic and transparent to you.

- Although it is possible for an individual to buy a System Builder copy of Windows 7 and install it on a new PC, that scenario is specifically prohibited by the license agreement, which requires that the software be installed using the OPK and then resold to a non-related third party. (As I noted in a September 2008 post, Microsoft once allowed "hobbyists" to use OEM System Builder software to build their own PCs, but the company switched to a hard-line stance on this issue sometime after Vista shipped in early 2007.)

- When you purchase a white-box PC from a system builder, the PC maker preinstalls the Windows version you purchased. The package you receive includes reinstallation media and a product key that is similar to a full packaged product but cannot be used for an in-place upgrade. You may or may not receive both 32-bit and 64-bit media. If you receive both types of media, you can switch from 32-bit to 64-bit Windows or vice versa by performing a custom reinstall using your product key.

[Update: As a consumer, you can buy an OEM System Builder copy of Windows from countless online shopping outlets. Technically, you're not supposed to use those copies unless you're building a PC for resal to a third party. But Microsoft's own employees and retail partners, and even its own "decision engine," Bing, aren't so clear on the rules. For a detailed discussion, see Is it OK to use OEM Windows on your own PC? Even Microsoft's not sure.]

All clear? Now let's move on to the next category: upgrades.

Upgrade versions

Let's assume you have a machine with Windows installed on it. Maybe you bought it preinstalled from a PC maker. Maybe you upgraded a previous version (like XP to Vista or Vista to Windows 7). Maybe you built it yourself with a full retail license. Whatever. Now you want to upgrade. You have two options.

Windows Anytime Upgrade This option is exclusively for people who already have Windows 7 Starter, Home Basic, Home Premium, or Professional installed. This might be the case if you get a great deal on a new PC with a specific edition of Windows 7, such as a netbook running Windows 7 Starter or a notebook running Windows 7 Home Premium. You now you actually want a more advanced version, but the PC is preconfigured and can't be customized. That's where Windows Anytime Upgrade comes in. You can use this option to replace your edition with the one you really want, with the features you need.

I did a complete walkthrough of the Anytime Upgrade process a few months back, and the process has not changed substantially since then. It is very quick (10 minutes or less, typically) and does not require any media. You kick off the process from the System dialog box in Control Panel and then enter a valid key for the edition you want to upgrade to. You can purchase a key online or use a key from any upgrade or full edition of Windows 7. The starting version must be activated before Windows Anytime Upgrade will begin.

When the upgrade completes, you are running the new, higher version. I have not tested the reinstall process yet. Officially, one would reinstall the original version and then use the Anytime Upgrade key to go through the upgrade process again. I am certain there are easier ways and will test them later.

Retail upgrade Here's the one that has caused all the recent controversy. A retail upgrade package is sold at a steep discount to a fully licensed retail product. The idea is that you are a repeat customer, and you get a price break because you already paid for a full Windows license earlier. Retail upgrades qualify for free technical support from Microsoft, even if the copy you're replacing was originally supplied by an OEM.

So who qualifies for a Windows 7 upgrade license? The Windows 7 retail upgrade package says "All editions of Windows XP and Windows Vista qualify you to upgrade." The same language appears on the listings at the Microsoft Store. Specifically:

- Any PC that was purchased with Windows XP or Vista preinstalled (look for the sticker on the side) is qualified. This is true whether the PC came from a large royalty OEM or a system builder. You can install a retail upgrade of Windows 7 on that PC. You cannot, however, use the OEM license from an old PC to upgrade a new PC without Windows installed.

- Any retail full copy of Windows XP or Windows Vista can serve as the qualifying license as well. If have a full retail copy (not an OEM edition) on an old PC, you can uninstall that copy from the old PC and use it as the baseline full license for the new PC.

- Older copies of Windows, including Windows 95/98/Me or Windows 2000, do not qualify for upgrading. There was some confusion earlier this summer when a page at the Microsoft Store online briefly stated that Windows 2000 owners could qualify for an upgrade. This appears to have been a mistake.

So, who doesn't qualify for an upgrade license?

- If you want to install Windows 7 in a new virtual machine, you need a full license. A retail upgrade isn't permitted because there's no qualifying copy of Windows installed. (The exception is Windows XP Mode, which is included with Windows 7 Professional and higher.)

- If you own a Mac and you want to install Windows on it, either in a virtual machine or using Boot Camp, you need a full license.

- And if you want to set up a dual-boot system, keeping your current version alongside your new copy of Windows 7, you need a full license. You can evaluate the new OS for up to 30 days before activating it, but if you decide to activate and use the retail upgrade full-time, you have to stop using your old edition.

That last one always surprises people, but it's right there in the upgrade license terms:

To use upgrade software, you must first be licensed for the software that is eligible for the upgrade. Upon upgrade, this agreement takes the place of the agreement for the software you upgraded from. After you upgrade, you may no longer use the software you upgraded from. [emphasis added]

So, if you want to dual-boot on a system that is currently using a single Windows license, you need to have a full license for your new copy, not a retail upgrade.

As the table on the first page indicates, you can transfer a retail upgrade license to a new PC. This fact confuses some people. Remember that the PC on which you install the upgrade must have a qualifying license first. So if you buy a new PC with an OEM Windows license, you can remove your retail upgrade from the old PC (restoring its original, un-upgraded Windows edition) and install your retail upgrade on the new PC. This is covered in Section 17 of the Windows 7 license:

You may transfer the software and install it on another computer for your use. That computer becomes the licensed computer. You may not do so to share this license between computers.

According to wording on the retail upgrade media, "This [setup] program will search your system to confirm your eligibility for this upgrade." It is, presumably, looking for evidence of a currently installed version of Windows XP or Vista, although the details of exactly how it does that search are murky, to say the least. I've written briefly about this recently and will have much more on the mechanics of the process later, after I complete some testing and interview some Microsoft engineers.

Full and Volume Licensing

I saved the high-priced spreads for last. The full license product represents the highest price you can pay as a consumer, but it also includes the most generous license. Big customers who are willing to buy in bulk can get full-featured editions of Windows, bundled with support contracts and special benefits, by signing up for Volume License agreements. Here's how these two products work.

Retail Full Package Product (FPP) This is the most expensive retail product of all and includes the fewest restrictions of any Windows version. You can install it on any PC, new or old. You can boot from the installation media and set up Windows 7 on a PC with a squeaky clean hard drive without having to jump through a single hoop. You can install it on any Mac, in a virtual machine or using Boot Camp. You can install it in a virtual machine in Windows as well. You can even use it as an upgrade for a previous edition (although you pay more for the privilege than you need to).

Two other noteworthy benefits of an FPP copy of Windows are these:

- You can uninstall the OS from a computer and transfer it to a new PC, something you can't do with an OEM copy of Windows. Microsoft briefly considered restricting this option when Vista was almost ready to launch but retreated in the face of a fierce backlash from customers

- You get free technical support directly from Microsoft, rather than from the hardware maker.

FPP products are premium-priced, but for some circumstances they make sense. And for customers who are willing to pay that premium to have no license hassles whatsoever, this is the way to go

Enterprise (Volume License) This is the most misunderstood of all Windows versions, in my experience. The most common misconception is that Volume Licenses allow a large company to buy Windows in bulk copies at discounted prices and then install them on any PC in their organization. The reality is very different.

I won't even try to summarize all the details of Volume Licensing or its companion program, Software Assurance. If you want those details, you can lose yourself for days or weeks digging into the official Microsoft Volume Licensing website. You can read the dry yet oddly entertaining (in a geeky way) Emma Explains Microsoft Licensing in Depth! blog, whose proprietor, Emma Healey of Microsoft UK, also has some useful FAQs. You can even earn a Microsoft certification with a Licensing Delivery specialization, a thought that actually makes me shudder.

With those caveats out of the way, here are a few essential facts about Volume Licensing:

- Volume Licenses are available for a long, long list of products, but for Windows 7, only Professional and Enterprise editions are available.

- You can qualify for Volume Licensing with as few as five PCs in an organization.

- All Volume Licenses are upgrades. You cannot legally buy a "naked" PC and attach a volume license to it. You must first buy a full license (typically an OEM license with a new PC purchase) and then use the Volume License to upgrade to the VL version you purchased.

- Volume License keys were a source of rampant piracy in the Windows XP era. As a result, all Volume License copies of Windows 7 now have to be activated, using either a Multiple Activation Key or a Key Management Service. The big difference with the latter option (which applies to most large VL customers) is that the activation servers are managed locally by the customer and individual employees don't have to activate using Microsoft's servers.

- According to Microsoft, a Windows Upgrade License purchased through a Volume License program is "tied" to the device to which it is first assigned and may not be reassigned. However, Volume Licensing customers who pay extra for Software Assurance coverage can reassign that coverage (which includes upgrade rights) to an appropriately licensed replacement device. If you find that confusing, join the crowd.

Disclaimer: I am not a lawyer, and this post does not represent legal advice. The information in this post comes from official Microsoft sources and represents my interpretation and belief based on my extensive experience with Windows. I believe this information to be accurate, but you should not rely on anything written here to make any buying or deployment decisions without reading the full license agreements. If you are concerned about your legal rights and responsibilities, you should consult an attorney and get any necessary legal advice for those issues.