Windows 10 subscriptions aren't happening. Here's why

We've had this advice drummed into our heads for years: If a deal sounds too good to be true, it probably is.

That guideline is usually correct, which probably explains why I continue to hear from skeptics convinced that Microsoft's free Windows 10 offer is a trap. Here's how the argument typically goes, as expressed in this actual excerpt from the comments to a recent post here:

Windows as a service, to me, means that they will eventually charge a subscription or something similar, to actually use your computer. [Microsoft] will make a very basic functionality free, but if you want to do anything of consequence, you will have to pay a subscription fee. That is the master plan, if MS can get away with it.

That sounds logical, if you believe that Microsoft is giving away something (a major upgrade) for which it could have collected revenue.

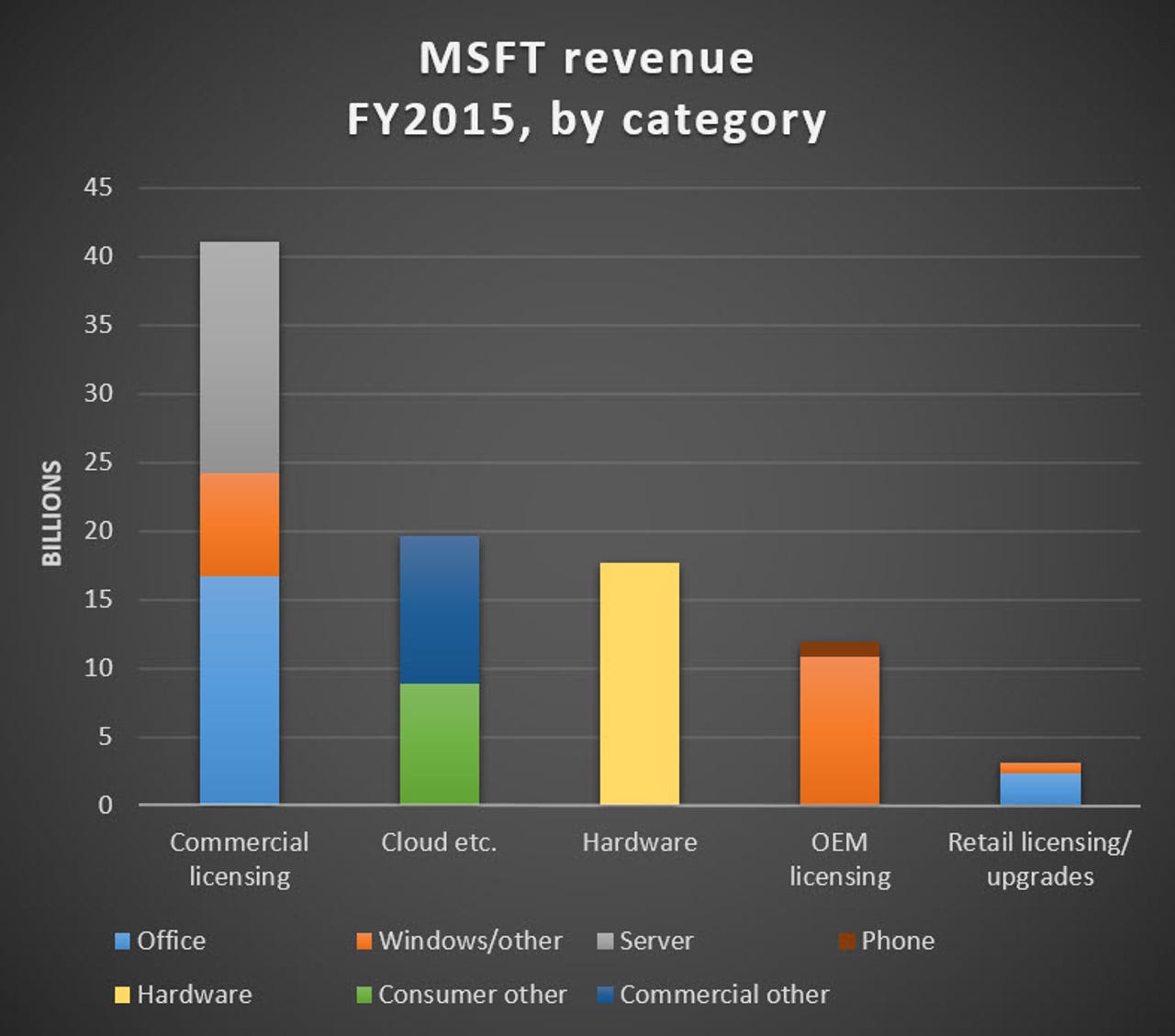

But that's the flaw in this argument. Windows upgrades have never been a major source of revenue for Microsoft, and the company's shift to the cloud has made that fact even more apparent. I wrote about this phenomenon last year, in "Microsoft's transition from traditional software to the cloud is picking up steam." Here's an updated version of the chart from that post, covering Microsoft's full fiscal year 2015, which ended a month before Microsoft's free Windows 10 upgrade offer began.

See that tiny sliver at the top of the smallest bar? That's how much Microsoft makes from Windows retail licenses and upgrades.

Microsoft took in $93.6 billion in revenue in fiscal year 2015. Nearly half of that total came from large companies paying for commercial licensing of server products, Microsoft Office, and Windows Enterprise edition upgrades.

Other big chunks of revenue came from cloud services (Office 365, Azure) and hardware (primarily Surface tablets and phones).

Contrary to what you might have heard, Microsoft isn't giving away Windows 10 for free. In the six months ending December 31, 2015, OEMs paid Microsoft more than $6.2 billion to install Windows on new PCs, with that amount including tens of millions of licenses for new PCs running Windows 10.

Meanwhile, in the last year for which we have figures, Windows licenses sold through retail channels, which includes upgrades and academic editions, constituted 8/10 of 1 percent of Microsoft's total revenue for the year. That's a mere drop in the bucket.

And that's been true for years.

Historically, those most likely to upgrade are likely to do so in the first few months of a new Windows release. That's why Microsoft has offered steep discounts for early adopters, and those prices have been plummeting over time. This chart shows the upgrade prices that were offered on launch day for the last four major versions of Windows.

Introductory prices for Windows upgrades, 2006-2015

Windows Vista Home Premium and Business upgrades were $159 and $259 on launch day. Ouch.

The introductory upgrade prices for Vista's successor, Windows 7, were described as a "screaming deal" at $50 and $100 for the Home Premium and Pro editions, respectively.

For Windows 8 Pro, the introductory upgrade price was $40. Windows 8.1 was a free upgrade. And now Windows 10 is a free upgrade for a very large number of people, probably measured in the hundreds of millions.

Microsoft isn't alone in this move, by the way. For OS X Tiger (2005) and Leopard (2007), Apple charged $129 for upgrades. The company made major headlines in 2009 when it dropped the price of the Snow Leopard upgrade to $29 per machine for many Mac owners.

Beginning in 2013, with Mavericks, OS X upgrades are free.

I don't see anyone complaining that Apple is about to spring a trap on its customers and start charging for subscriptions.

The point is, Microsoft isn't giving up a significant amount of revenue. For consumers and small businesses, feature upgrades are now just another category of update, delivered for free the same way other updates have been for decades.

Businesses that want advanced features, such as BitLocker Drive Encryption, the ability to join a computer to a Windows domain, and Hyper-V virtualization capabilities, pay an average of about $50 extra for a Windows Pro license, usually with a new PC. But that's a one-time cost, not a subscription.

On the other side of the ledger, Microsoft simplifies its business by moving the bulk of its installed base to a single version. Having fewer versions to support means lower costs for engineering and testing and, at least in theory, a more reliable and secure platform overall.

Meanwhile, large enterprises, including corporate customers and government agencies, actually have been paying for Windows subscriptions for many years, thanks to a volume licensing program called Software Assurance. That annual fee gives them a slew of enterprise features and usage rights that consumers and small businesses don't need and certainly won't pay for.

I'm not even sure how a Windows 10 subscription for consumers and small businesses would work. What features in the operating system would Microsoft charge extra for? I've asked that question of people who are convinced that Microsoft has an evil master plan to soak its customers with subscription fees, and I have yet to hear an answer that makes sense.

Of course, there is a subscription product that has been very successful for Microsoft. The company has been steadily moving consumers and business customers away from traditional Office licenses and towards Office 365. At $99 a year and up, that's an extremely lucrative market.

There are also multiple business services that Microsoft sells on a subscription basis. Dynamics CRM, Microsoft Intune for management, and OneDrive (although it's bundled with Office 365 making the standalone product unnecessary), to name a few. And of course there's Azure, which uses a combination of subscription and usage charges as its model.

All of those services are dramatically different from Windows. The Office apps are designed to install on multiple devices so that you can be productive at your desktop or on a laptop or a tablet. Most of those management services run in a browser. An operating system like Windows, on the other hand, is designed to power a single device.

The other huge opportunity for Microsoft in the consumer market is gaming. In the six months ending December 31, 2015, the company made more than $5.5 billion in this segment, nearly as much as it made from selling Windows to OEMs.

Xbox hardware sales were down, but Xbox Live revenue grew by a very healthy 21 percent, and revenue from video games was up an even more impressive 52 percent, thanks to sales of Minecraft and the launch of Halo 5.

Those sales are much easier when the underlying device is running an up-to-date operating system, which is yet another reason for Microsoft to avoid tampering with its traditional Windows licensing model.

Yes, Microsoft's cloud-first business model provides lots of opportunities for them to sell software as a subscription. But Windows 10 isn't going to be on that list.