Flashback malware exposes big gaps in Apple security response

In one of those great ironies of technology, an increased incidence of malware is a sign that your product has been a success in the market.

Apple’s been astonishingly successful with its Mac hardware in recent years. The dark side of that success is the attention they’ve begun to attract from online criminals.

Apple and its customers got a hint of what was in store with last year’s Mac Defender outbreak. This year, a much larger and more disturbing outbreak has infected more than 600,000 Macs with a piece of malware called Flashback.The entire Flashback episode has in fact exposed Apple’s security weak spots.

Eugene Kaspersky last week argued that Apple is “ten years behind Microsoft in terms of security.”

Those aren’t just self-serving statements from a company that sells security software. Kaspersky’s argument didn't even mention antivirus solutions. Instead, he said, Apple’s security efforts have been slow, reactive, and generally ineffective:

We now expect to see more and more because cyber criminals learn from success and this was the first successful one. [Apple] will understand very soon that they have the same problems Microsoft had ten or 12 years ago. They will have to make changes in terms of the cycle of updates and so on and will be forced to invest more into their security audits for the software. That’s what Microsoft did in the past after so many incidents like Blaster and the more complicated worms that infected millions of computers in a short time. They had to do a lot of work to check the code to find mistakes and vulnerabilities. Now it’s time for Apple [to do that].

Let’s be clear: Both Microsoft and Apple are victims of organized crime in all of these attacks, and they’re in the unenviable position of having to fight legal battles and make substantial engineering investments on behalf of their customers. It is, unfortunately, a cost of doing business.

See also:

- New Mac malware epidemic exploits weaknesses in Apple ecosystem

- Second source confirms: 1 in 100 Macs are infected by Flashback

- New data shows older OS X versions more susceptible to malware

- Apple releases Flashback removal tool, infections drop to 270,000

- How big a security risk is Java? Can you really quit using it?

All complex software has vulnerabilities, even when it’s written with the most disciplined processes. Bad guys make a lucrative business out of finding those vulnerabilities and writing exploits for them. Eliminating malware completely is a pipe dream, especially on relatively open platforms like Windows and OS X. No one seriously believes it’s possible to eliminate street crime, either, but effective policing and attention to the underlying causes of crime can significantly reduce rates.

A lot of what Apple is learning about security today will show up in future editions of OS X and iOS, as the company presumably gets smarter about writing code. But what about the 60 or 70 million current Mac owners?

They have a right to expect much more of a security response from Apple than they’re getting now. As an Apple customer myself, I believe Apple deserves four key criticisms of its current approach to security.

1. Apple is too slow to deliver updates

When the size of this incident first became apparent, I wrote:

What makes this outbreak especially chilling is that the owners of infected Macs didn’t have to fall for social engineering, give away their administrative password, or do something stupid. … The Flashback malware in its current incarnation does not use an installer. It does not require that the user enter a password or click OK in a dialog box. It is a drive-by download that installs itself silently and with absolutely no user action required, and it is triggered by the simple act of viewing a website using a Mac on which Java is installed.

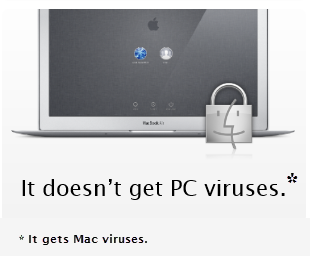

Apple brags that it is quick to respond to security issues. Here, for example, is what you see if you visit Apple's "Why you'll love a Mac" page:

Unfortunately, that bold statement is contradicted by the facts.

Apple's update that fixed the Java security hole was released April 3, 2012. That’s 49 days after Oracle released Java SE 6 Update 31 for all other platforms. During that seven-week period, every Apple customer who had Java installed (and that includes every Mac owner running Leopard and Snow Leopard) was vulnerable to a silent installation of malware. Ultimately, Apple had to release an update that fixed the security hole and removed the malware already installed on its customers' Macs.

That long gap in Apple's response is not unusual, as independent security expert Brian Krebs has pointed out:

Apple maintains its own version of Java, and as with this release, it has typically fallen unacceptably far behind Oracle in patching critical flaws in this heavily-targeted and cross-platform application. In 2009, I examined Apple’s patch delays on Java and found that the company patched Java flaws on average about six months after official releases were made available by then-Java maintainer Sun.

Apple’s performance in recent years has been much better in terms of Java updates, but still slow. Oracle has released six security-related updates to Java SE 6 in the past two years. In five of those six updates, it took Apple at least three additional weeks to release its version of the update. Two of Apple's updates arrived more than 30 days later than those available to other platforms.

So what happens when the next Java vulnerability is discovered and patched by Oracle? How long will Mac users have to wait for their updates? Or, to put it another way, how much of a window of opportunity will malware authors have to attack Macs?

Page 2: Update hassles and abandoned Macs -->

<-- Previous page

2. Apple offers no automatic update option

Even when updates are available, they’re only effective if they're applied. And every security researcher knows that a nontrivial percentage of users simply ignore updates.

As Mac expert Glenn Fleishman noted the other day (via Twitter), “Legions of children manage updates for parents and grandparents.” That's because they know that, left to their own devices, many unsophisticated users will simply postpone those updates by clicking the “Not Now” or "Install Later" button. They see updates as an annoyance that will mean they can’t use their Mac for 10 minutes to a half-hour.

So how bad is the problem? Based on data collected by Dr. Web, roughly 1 out of every 4 Snow Leopard users are at least six months behind in terms of applying major software updates. Nearly 15% are more than a year behind, meaning they have skipped at least two major OS X updates and are easy prey for any exploit that targets security holes that were fixed in those updates.

User education only goes so far. When you go home for the holidays, you can configure Software Update so that it downloads new updates automatically. But you can’t set up OS X to install those updates automatically, as you can with Windows.

Automatic updates would not, of course, bring the percentage of up-to-date installations anywhere near 100%. But it could make a difference for a few percent. And in a user base of 70 million (and growing), even a 3% improvement means 2 million Macs that are better protected than they are today.

3. Apple is too quick to abandon its customers

Although Apple has never said so publicly, it’s common knowledge among Mac experts that Apple provides updates (security and otherwise) only for the current OS X version and the most recent.

That means Macs that are between three and five years old are left unprotected unless their owners pay for an upgrade to a new version of OS X. (Apple charges $29 to upgrade from Leopard to Snow Leopard and another $30 to upgrade from Snow Leopard to Lion.)

According to Dr. Web’s data, 25% of all Flashback-infected Macs are running Mac OS X 10.5 Leopard. Net Market Share statistics suggest that at least 17% of all Macs in use today are running Leopard (or an earlier version of OS X).

Leopard shipped August 25, 2007. It was sold on new Macs for two full years. Customers purchased 5.7 million computers with Leopard installed in the first half of 2009. Those computers are all roughly three years old today, and most can expect to have at least two or three more years of useful life. Apple does not provide updates to these computers unless the customer purchases and installs a new version of OS X.

Snow Leopard (Mac OS X 10.6) shipped August 28, 2009, and was on sale for almost two years, until Lion shipped on July 20, 2011. It is still the most popular version of OS X today, according to these March 2012 Net Market Share figures:

If Apple maintains its current policy, then as soon as OS X Mountain Lion goes on sale, probably in July or August, Apple will drop support for the Macs it sold with Snow Leopard installed. Every one of those unsupported Macs will be three years old or less.

Or, to put it another way:

Apple sold about 27 million Macs in 2009 and 2010. By the end of this summer, in September 2012, every one of those Macs will be unsupported in its original, as-purchased configuration.

Microsoft has a support lifecycle of 10 years for each version of Windows. While that may be too much to expect of Apple, it’s clear that there’s a radical disconnect between the useful life of Apple hardware and the company’s support for the combination of hardware and software that it sells.

Users have many reasons besides cost to avoid the headaches of upgrades. I’ve yet to read an enthusiastic review of OS X Lion, and I’ve heard many people compare Lion to Windows Vista.

But the point is, Apple offers its customers the choice of whether to upgrade to a new OS. The company shouldn’t be allowed to refuse to deliver essential security updates to Macs that are three to five years old. That’s gross negligence.

4. Apple doesn’t communicate well

Apple’s first public statement that mentioned the Flashback malware outbreak came on April 14, with a support bulletin titled “About Flashback malware.” That was more than a week after security researchers and news sites like ZDNet had sounded the alarm. In its Java updates on April 3, Apple did not communicate any sense of urgency, even though they had to have known by that time that exploits were in the wild and wreaking havoc on Mac owners.

Apple doesn’t communicate well with security researchers, either. Boris Sharov, chief executive of the Moscow-based security firm Dr. Web, told Andy Greenberg of Forbes that his researchers were ignored when they tried to contact Apple with their findings: “We’ve given them all the data we have. We’ve heard nothing from them…” The only contact from Apple, in fact, was a demand to take down the “sinkhole” domain that Dr. Web researchers were using to study the distribution and behavior of the Flashback botnet.

To this day, in fact, Apple has not issued any statement aimed at the general public or the mainstream news media. Apple’s dilemma is a painful one here: If they talk to the press in an effort to reach owners of Macs who aren’t aware they’ve been infected, they risk puncturing the “Macs don’t get viruses” image they’ve cultivated through the years. So the company has chosen to remain silent, which is shameful.

Apple’s legendary secrecy is an asset when it comes to product development and launch-day hype. Somehow, the company has to overcome that desire for secrecy when it comes to security.

For its customers' sake, it desperately needs to think different.