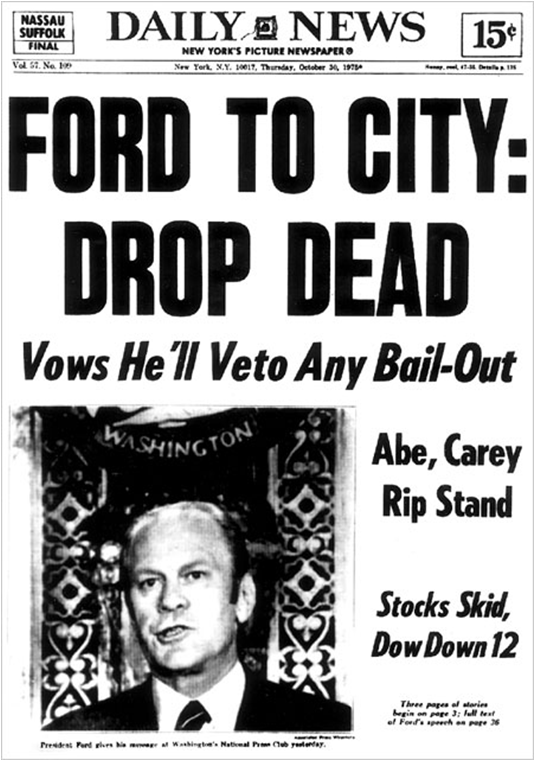

Microsoft to advertisers: Drop dead

(You can see a scan of that iconic page to the right.)

Fast forward to the technology industry in 2012: you'd think, based on the advertising industry's reaction, that Microsoft said the same thing to it when it announced yesterday that the next version of its web browser, Internet Explorer 10, will ship with its "Do Not Track" feature turned on by default.

The feature sends a message to each website you visit stating that you, the user, prefer not to be tracked. Obeying the message is optional.

This morning, everyone's freaking the hell out. Wired calls the move a "nightmare" for ad networks, and the Digital Advertising Alliance felt the need to weigh in, expressing anger that Microsoft -- a partner -- would just go and make a decision without consideration (read: compliance) for the "consensus achieved over the appropriate standards for collecting and using web viewing data (and which today are enforced by strong self-regulation)."

Funny how a simple on/off switch has so many people pissed off. The end of behavioral advertising is nigh!

First, let's get the facts straight:

- Mozilla first introduced the feature earlier this year, in Firefox 4. Unsurprisingly, advertisers didn't like it. But it wasn't on by default.

- The spec for the feature is mostly concerned with the technical approach to it -- that is, it's mostly concerned with the hurdles to standardize such a feature, not the ethics of applying it.

- Today's advertiser-approved solutions are largely opt-out, not opt-in, mechanisms. And they're often temporary -- the Network Advertising Initiative's tool is hardly a Do Not Call list.

- Microsoft believes "that consumers should have more control over how information about their online behavior is tracked, shared and used," chief privacy officer Brendon Lynch wrote in a memo yesterday. Part of that choice is deciding whether or not they want to receive more relevant advertising. And here's the touchpoint: "[DNT] advances the idea of privacy as the default state."

- DNT is supported by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission.

Until now, behavioral advertising on the Web has been the Wild West of business. Since technology legislation tends to be reactive, not proactive, advertisers have been zealously taking advantage of a massive proliferation of user activity data -- collected by your favorite platforms, such as Google and Facebook -- with advertisements that seem utterly creepy in how well they know you -- or not.

There has been a lot of A/B testing on what works within behavioral advertising, but there doesn't seem to have been as much on the practice as an effective approach relative to both the performance of ads and user experience -- though to be fair, we can't know what a world filled with behavioral targeting is like until we occupy one for a little while.

Now we have, and it feels increasingly like this.

In many ways, behavioral targeting is a good thing for both business and the consumer. Granular data about users allows advertisers to make their wares much more relevant to users, which means that they theoretically won't have to be so desperate (roll-overs, pop-ups, etc.) to get their attention. And it could be helpful to the user -- after all, if you're in the market for a new PC and a discount is advertised to you on a system you want, who wouldn't take it?

But it hasn't quite worked out that smoothly. Aside from the cultural shift that such technology is requiring -- remember when we were all concerned with what personal information we posted in chat rooms? Ha! -- it's also enabling a lot of personal data abuse.

Have you had any ads specifically call out your name, location or organizational affiliations? "Andrew, you should try Ketel One!" (I don't drink vodka.) "Since you're a CBS employee, you should try our cut-rate dental plan!" (Uh, no.) "Click LIKE to show your support for the Ivy League!" (How about I click "dislike" to show my apathy for such poor advertising?)

I share with you two more anecdotes:

The first: I'm writing this post from Paris, France, where all of the ad network display advertisements I see on the web -- despite being an English-speaking American -- have suddenly turned French. (I don't need a Renault, guys! Really! And that other ad? I don't even know what it says!)

The second: When I got engaged in 2010, and my (now) wife and I changed our statuses accordingly, she was pummeled with ads about wedding planning and dresses and catering and you name it. (Oddly, and perhaps deserving of further sociological scrutiny, I was not.) When we tied the knot, all her ads turned to...baby planning. (No thanks, we're good for now!)

In practice, all behavioral advertising has managed to do is annoy the hell out of me...on a personal level. It is a much deeper level of rejection than seeing a billboard I disagree with on the highway, because I know there's an attempt being made that's failing. But I don't have the time or energy to swat all of these new digital mosquitos. As a gatekeeper to the web, Microsoft is taking a step to do that for me -- and all the average web-using people who have no idea what's going on and couldn't tell you the name of the current U.S. vice president, much less what a cookie is.

Yet behavioral advertising retains its potential, its allure. That's what we're seeing here in this latest flareup: advertisers see it as an attack on the technology and their stewardship of the issue; Microsoft sees the current practice of it as an attack on users' quality of life, and is temporarily taking control of it.

And so each party talks past the other. Ad infinitum.

The truth is, we don't know what's going to happen as Microsoft rolls out this feature. In fact, we should all support the decision -- if only to gather data on how it impacts user behavior, and subsequently compare it to the on-by-default option. Are users more, or less, engaged? Are they more, or less, peeved? (It's not like they're going to stop using the web in protest.) Are online advertisers making more, or less, money?

None of this should require additional action by the user, and that's why both sides are at odds.

The DAA says Microsoft's move "threatens to undermine that balance, limiting the availability and diversity of Internet content and services for consumers." The way I see it, the move restores some balance to the issue of whether behavioral advertising has proven to be advantageous or not. It's a slap on the wrist of an industry that occasionally runs amok -- not as a form of punishment, mind you, but a way to limit the collateral damage we keep seeing.

Because sometimes I just want an ice-cold can of Coca-Cola, and it has nothing to do with how old I am or where I live or who I work for. (But maybe, just maybe, how deathly hot outside it is right now.)

Good behavioral advertising can accomplish that. But too often, it hasn't.