SaaS pricing evolves: Should we be worried?

Software as a service pricing schemes are getting more complicated and raising questions about lock-in, whether long-term deals are true to the spirit of cloud computing and what kind of deals IT buyers are really getting.

Now you can't paint all SaaS pricing with a broad brush. A collaboration provider will have different economics---and may be more amenable to pay-as-you-go deals. Other companies that handle more complicated implementations---think Workday or Salesforce.com---may like longer-term contracts.

Anecdotal evidence is showing that large enterprise SaaS contracts aren't exactly pay by the sip anymore. And some of these deals look like your standard licensing and maintenance deals---still cheaper though. The big question is whether this development is worrisome.

In any case, the SaaS pricing conversation is worth having. Jason Hiner and I recently talked SaaS/cloud pricing on a recent Webcast. In addition, NIST has also included key pricing tenets as it works to define cloud computing. According to NIST, "rapid elasticity" is an essential characteristic of cloud computing, which includes various flavors of "as a service." NIST said in its latest definition statement:

Capabilities can be rapidly and elastically provisioned, in some cases automatically, to quickly scale out and rapidly released to quickly scale in. To the consumer, the capabilities available for provisioning often appear to be unlimited and can be purchased in any quantity at any time.

Add it up and SaaS pricing is an issue that's starting to bubble up.

What follows is a synopsis of a long-running---not to mention fascinating---conversation about SaaS on the Enterprise Irregular mailing list.

SaaS pricing dynamics changing

It's an open secret in the IT industry that SaaS companies often are pushing multi-year deals that more resemble the licensing arrangements by on-premise vendors. On the surface, SaaS providers get predictable revenue streams and customers also get costs they can easily forecast. This predictability matters for large enterprises and the SaaS vendors increasingly catering to them.The big questions: Is this really SaaS pricing as initially conceived? And will SaaS buyers be screwed?

After all, the vision of SaaS is that we'd all subscribe to our software and have the freedom to come and go as we please. Multi-year deals mean that you're a bit locked in---sound familiar?

Some analysts like Ray Wang are concerned about these developments. Wang argues that IT buyers should be worried. Wang argues that the key tenets of SaaS---pay as you go, seamless updates, all-in costs---are being eroded for long-term contracts, termination for cause and pricier support programs.

AG Customer Bill of Rights - SaaS - Live

However, you can also argue the not-so-SaaSy pricing models are justified. Enterprise software is complicated and the economics simply don't work if there isn't some longer-term commitment. SaaS companies couldn't take the churn. Pay as you go may not work in the enterprise.

Bottom line: Pay-as-you-go enterprise software pricing is a bit of a myth for most large complicated companies. There's also another reality: Switching costs even from SaaS are enough to keep you in the fold.

How did we get here?

When you think about the evolution of SaaS vs. on-premise software rivals there's one glaring difference: Profit margins.Oracle CEO Larry Ellison has quipped that SaaS just doesn't bring home the bacon. Indeed, Salesforce.com, arguably the most successful SaaS company on the planet, is on an annual revenue run rate of about $1.5 billion. For Oracle, that sum is barely material.

Needless to say, it's pretty clear why SAP is just now getting SaaS religion after three years. What's the rush when you can make more money elsewhere?

SaaS is still cheaper when you consider you don't need to manage servers or hire the people to handle that gear. Simply put, SaaS still passes on savings to customers, but it may not be cheap as appears on the surface.

In many respects, this SaaS pricing---and the complications that go with it---makes a lot of sense if you follow the money. Vinnie Mirchandani on one thread noted that SaaS is similar to the evolution of offshore outsourcing firms. At first, these Indian upstarts could undercut IBM and Accenture by 10 times or so. Then they move up stream, both the established guys and the upstarts poach tactics from each other and the cost advantage narrows.

The big question that's left hanging: What are so-called normal software profit margins supposed to be? Customers don't see 90 percent profit margins as sustainable. Are SaaS profit margins the new normal a decade from now? Or will software profits meet somewhere in the middle of on-premise and cloud applications?

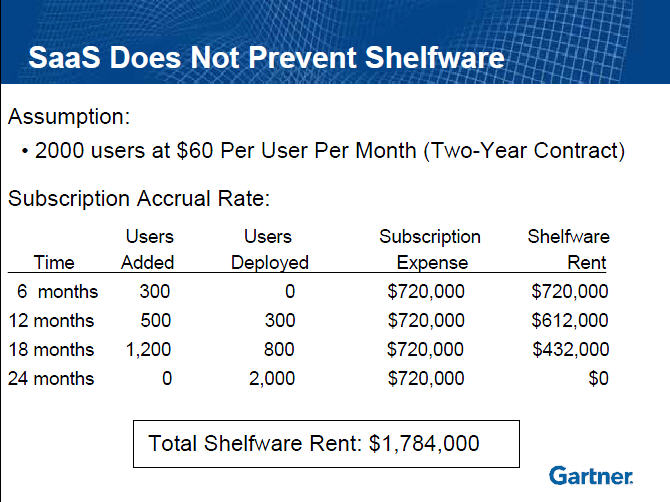

Related: SaaS: Shelfware as a service?

The tug-of-war

Some companies are looking at this SaaS pricing evolution and highlighting the topic. RightNow, which provides customer service applications as a service, in March introduced what it calls a "cloud services agreement."Some of the tenets of the RightNow agreement go like this:

- Vendors need to align usage up and down. SaaS should have shelfware. Think billing like an electric company, not a 1 to 3 year agreement.

- SaaS players should offer a minimum of 5 years of pricing transparency and 3 years of guaranteed pricing.

- Customers should be able to terminate for convenience.

- SaaS companies should offer annual pools of capacity.

- There should be cash service credits if service levels fall short.

Jason Mittelstaedt, RightNow's chief marketing officer, said the company's cloud service agreement has been well received by customers. Indeed, RightNow said 9 out of 14 large deals it inked in its most recent quarter were based on the cloud services agreement.

The big question is whether other SaaS vendors will follow RightNow's lead. Mittelstaedt says "smaller more nimble vendors" are interested in the concept because it's could win them business and they have nothing to lose. Larger players may not be so quick to follow suit. "If SaaS shelfware is 30 percent of your business you can't introduce this (the cloud services agreement) because it could be millions of dollars," says Mittelstaedt.