Wireless service boosters: A good idea but we shouldn't have to pay extra

You would think that the news of an AT&T Femtocell product - basically, a network extender that can help boost a weak cell phone signal in homes and buildings - would be a welcome product, especially for the iPhone users who regularly have to deal with dropped calls.

But could there be some backlash over the MicroCell 3G product - which is currently being tested in the Charlotte, N.C. region - because of the pricing? I couldn't help but nod in agreement as I read blogger Adam Frucci's rant in Gizmodo, who argues that the device and service for these network extenders should be free. Consider the reasoning in this excerpt from Frucci's post:

Basically, AT&T didn't have a strong enough network to handle the iPhone. It still doesn't. Yet they still charge about $100 per month on average to iPhone customers, who have to deal with dropped calls, delayed voicemails and unreliable 3G speeds. If you are in a particularly bad spot, the 3G MicroCell will let you run your calls and data through your internet connection rather than over their shit network.

Where do they get off charging for this? Femtocells will actually reduce the load on their networks. It shifts the traffic over to the internet provider you're already paying for (which I'm sure ISPs will just love). How does this earn AT&T $20 per month?

Amen, brother.

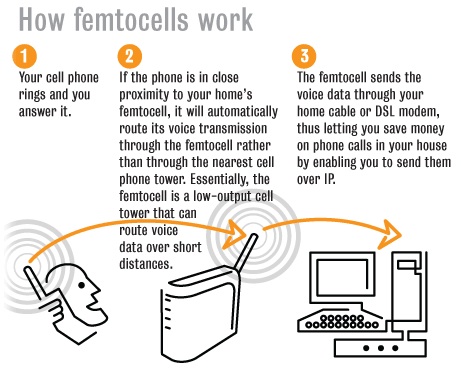

Last year, I wrote about AT&T testing a product based on Femtocells, which are low-power wireless signals that, when used with a broadband connection, can create a miniature cell tower effect in your home or business. Given how wireless network dead zones are just a reality of life these days - even for the best of them in some locations - these sort of products make sense, especially for households that long to cut their ties to a landline phone.

For a while now, I've been test-driving Verizon's Femtocell product - called the Network Extender - to help boost the signal in my own home. I consistently get a signal of some sort, though it used to often fade down to one or two bars. (Silicon Valley is covered with signal-blocking foothills and other obstacles.) The network extender - which is plugged into my home router - does a good job of consistently boosting the signal.

Graphic credit: NetworkWorld

The $249 that Verizon charges for the device is hefty but it's just a one-time investment - no monthly charge. Why is the monthly fee such a deal-maker/deal-breaker? Because it's a monthly reminder to the customer that they're paying extra for something they should have been getting in the first place - reliable service. Again, Adam sums it up nicely:

It's ludicrous. If their network was solid, these MicroCells wouldn't even need to exist. AT&T is cutting off your arm and then trying to sell you some bandages. Hey, AT&T: people are already paying you for cell service. You can't charge them again for the same service. Fix your f---ing network.

To be fair, the same could be said about any of the carriers. Sprint's Airave device costs $100 and has a $5 per month service attached. T-Mobile's HotSpot@home service is $10 per month and requires a T-Mobile router. Under the Verizon model, users have to get past the sting of coughing up $250 for the product but then don't have to worry about a recurring charge.

At the same time, if enough customers start paying extra for these network extenders and the carriers start to see some extra revenue monthly service fees, why would any of them rush to upgrade their networks and eliminate the need for these Femtocell products? They could just keep milking us forever, forcing us to pay a premium for a quality of service that should've been there in the first place.

Of course, once we start tapping into the broadband connection at home to make up for the shortcomings of the wireless carriers, the ISPs will likely start squawking about using too much of their data pipeline and put out their hands for a bigger monthly service fee, as well.

One final thought: Isn't AT&T both wireless carrier and ISP?