Twenty-two power laws of the emerging social economy

Traditional measures of business success are becoming less and less important.There is a time for big picture thinking and there is a time for details in business and IT, the latter which make business and technical strategy a reality and the former which provides needed direction and focus.

Highlighting the big picture side last week we saw Steve Ballmer's exploration of the efficiencies he believes are being driven by something he calls "the new normal". In this view, he tries to frame up how a reset of economic expectations during the downturn has created an environment that is putting pressure on business to do more with less, affecting IT at least as much as the rest of the organization, if not more.

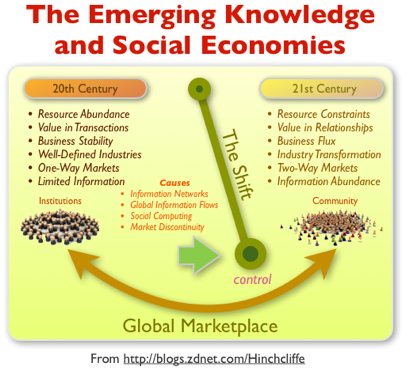

If we factor out the commonalities in these views, it highlights a core set of strategic trends in IT and business in 2009, namely:

- New resource constraints. Today's new economic baselines (the downturn, green business, etc) are requiring that we find ways to accomplish our goals using fewer resources. This includes identifying the means to capture opportunity and transform "in process" business activities using newer, more efficient models. Business leaders will need to effectively link IT and business much more so than in the past to accomplish the movement to this new baseline. This also doesn't mean everything is constrained. As we'll see on the technology side, abundance is being produced that may address shortcomings in the business side.

- Value shifting from transactions to relationships. This is the growing realization that the traditional rote business transaction as the core source of organizational value is diminishing and value is now coming from relationship dynamics. This has many implications including using new management methods (example: from top down command-and-control to community curator and facilitator), tapping into new reservoirs of innovation, adopting new ways of interacting with customers, or driving better tacit interactions. Web 2.0 and social computing will be key enablers of this for business units and IT organizations that want increased relevance.

- Industries in flux with new ones emerging. Previously stable industries such as finance and media are feeling the pinch the strongest, but most others are as well. The recession is creating a bigger gap between healthy and unhealthy businesses while many industries are being unbundled or transformed into new ones (traditional software companies moving to SaaS and cloud computing for example or the rise of crowdsourcing competing with outsourcing at the low end.) Again, today's dynamic Web-driven global knowledge flows and agile online models for computing and collaboration -- as well as economic and intellectual production -- are now a significant change agent.

- Moving from change as the exception to change as the norm. Today we're seeing faster consumer behavior shifts, quicker pricing changes, more rapid product cycles, and faster media feedback loops. While this can also lead to more extreme market conditions, it also enables opportunities to be turned into bottom-line impact for organizations that can adapt to market realities quickly enough. The network is the culprit (and solution) for much of this again: We now have pervasive social media instantly transmitting and shaping cultural phenomenon and faster financial cause-and-effect in the markets, real-time online markets, and so on. In the 21st century, following a plan is increasingly less important than responding actively and effectively to change.

- A shift of control to the edge of organizations. This has been predicted at least as far back as the Cluetrain Manifesto, if not farther. It's not even really a shift, it's more like the addition of a new dimension to how we operate organizationally, something I've referred to previously as "social business." This new addition changes the dynamics of where useful information comes from, how decisions are made, and how more autonomy and self-organization will be needed (and tolerated) in modern organizations to meet more dynamic and changing global marketplace.

As I explored recently in "How the Web OS has begun to reshape IT and business", today's Internet has become a central driver of how we do things today. It's the richest marketplace that we all have roughly equal access to (all our customers, all the data, the infrastructure, services, and all our competitors). In short, it's fast becoming the essential fabric of modern business and economics. I noted in that piece as well:

"IT is going to either have to get more strategic to the business or get out of the way. Businesses too must grow a Web DNA."

The post-industrial knowledge economy becomes more social

But what are the forces that drive success on the network, either Internet or intranet? It seems like traditional measures of success such as having a high market share, bestseller products, brand dominance, good physical business location, 1-on-1 customer relationships, and a host of other factors are becoming less important. The discussion over the last 5 years with major shifts such as Web 2.0 has instead been famously about things like network effects, The Long Tail, peer production, and even Metcalfe's Law.

These are fundamentally different ways of thinking about our businesses as the social dimensions in the workplace expand and transform. Note that the social aspect of businesses has always been present in real-life interaction. But now it's more and more online just as our economies also move away from both manufacturing and transactions to one where creating, managing, and leveraging intellectual capital is the dominant activity. This has sometimes been referred to as the knowledge economy and one of its key traits is an environment where abundance of the fundamental resource (information) is common and scarcity is rare.

Related: Many of these changes are reshaping enterprise architecture as well.

The move to a knowledge economy is already here as we head well into a post-industrial age, at least in developed countries. A detailed 2007 report prepared for the European Union found that 40% of jobs in Europe were already in the knowledge economy and found approximately the same for the U.S, with a 24% overall 10-year growth trend. These are seismic shifts in terms of where and how we focus our business strategy, spending, hiring, and management. Government support for a knowledge economy is essential as well, with policies easily able to penalize firms attempting to make the move to these new models. Like Web 2.0, the impact of this is not months or even years, but a decade or two. See Amara's law, below.

In the list presented below, I've summarized some of the likely rules of a rapidly emerging new "social economy". While many of the old business rules are still likely to be true (as the second crash shows, bubble economics need not apply), the fact that business is moving to a much more network-driven model has certain inevitable consequences. That these rules are partially responsible for the creation of modern Web giants such as Google, Amazon, Facebook, and now Twitter is almost certain. That we know how to apply them effectively to our traditional businesses is much less so.

Twenty-two power laws of social economics

First a quick explanation of power laws. The term "power law" has a much more specific meaning to those that follow such things. In general, a power law defines when the frequency of an event decreases faster than the increasing size of the event. The classical example is that an earthquake twice as large is four times as rare. Power laws are found throughout nature and human environments and are an active area of scientific research that have attracted widespread interest.

However, the list below is more informal and though a number of power laws are on the list, I'm using the term merely to imply that these principles and relationships drive directly to the heart of way network-based social systems function. There are two components at interplay here: the network and us. The way they interact and entangle is what is increasingly both interesting and important to the knowledge economy. This is especially true of a distinct and burgeoning part of it I'm called the "social economy" here for convenience. As I explored earlier this year, it's a rapidly growing part of the overall knowledge economy, yet there many poorly understood implications to this. Ultimately, the social economy comprises all things we call enterprise social computing, social media (at least in terms of its application to business), and Enterprise 2.0.

Many of these have a great deal of research, data, and math behind them (Reed's Law) while others are just statement of apparent social truths (The Tinkerbell Effect) that can inform our thinking. While the former makes structured thinkers, determinists, and architects more satisfied that the social part of the knowledge economy can be controlled and quantified, it also appears that the more intangible aspects of the way people work that often drives the real success of social systems. See last week's discussion on community management as a prime example.

Here then, are some of the rules that seem to guide this new social economy, in alphabetical order.

1. Amara's Law

Amara's Law (backstory) states that "we tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run." This is just about true of any major technology shift: There is a hype cycle effect that governs the perception of the new approach. Soon after initial adoption there is disillusionment as the expected transformation failed to happen as quickly as it was expected to. Finally enlightenment blooms as effective use takes hold, longer down the road than expected. This model is now even a popular research presentation approach from Gartner. This is one of my favorite laws and I do see this in effect quite often in traditional businesses with an Internet division: The traditional side of the business is growing in single digits (if they're lucky) and will be for the foreseeable future. On the Internet side, the business is growing in the low to middle double digits. If you plot this forward 3-5 years, the Internet division will be almost as big as the traditional business or bigger, yet most management is still focused on the old business and not the new "sideshow".

2. Beckstrom's Law

Originally formulated by Rod Beckstrom (currently head of ICANN), Beckstrom's Law is a way of calculating the actual value of a network (versus the theoretical maximum potential, which is what Metcalfe's Law and Reed's Law determine). The premise is that by removing the network and calculating alternative ways of doing things, you can find out the true value of a networked business process. Of course, the gap between this value and the potential value of a network (as a product, service, or community) is a measure of the true untapped business opportunity remaining. Techniques like actively leveraging network effects can help realize these to a fuller extent. This model is also useful for conducting ROI calculations of social computing efforts.

3. Dunbar's Number

While subject to a variety of debates, Dunbar's Number remains a useful warning that we all have limited social capacity. Estimated to be around 150 active connections, it's the number of social relationships that the average person can effectively maintain before overload occurs. Organizations have used numbers like this for many years to organize the structure of departments or military units for maximize effectiveness and cohesion. While we might be gaining additional social capacity because of the software tools we now use that augment our ability to manage our social graph, there is still ultimately limit. The design of social systems in the enterprise and otherwise must take into account that social involvement and attention can be exhausted.

4. Gilder's Law

This states that network bandwidth triples every 18 months. While the research I've seen has shown that this law continues to hold, it basically means that raw communication capability is improving faster than computing power is increasing. This has led to some other shifts in the industry lately, but for the moment, it means the cost of communication, no matter how complex, is collapsing rapidly towards zero and will be for at least the next 5 years based on current trends. In practical terms, in means that we can be increasingly wasteful of communication resources to cost effectively achieve our business goals. Gilder's Law is one of the key drivers of prevalent abundance on the technology side that we can funnel towards business objectives.

5. Goodhart's Law

The idea here is that once a social or economic indicator or other artificial measure is made a target for the purpose of management or conducting social or economic policy, then it will lose the information content that would qualify it to be effective or meaningful. It's a counterintuitive principle, and Goodhardt's Law shows that social systems often exhibit dynamics that are much different than logic on the face of it would suggest. This has deep implications for social computing adoption, community metrics, and rewards and motivations for stated objectives using social models.

6. The Hawthorne Effect

Going hand-in-hand with the Goodhart's Law and its implications, the Hawthorne effect demonstrates that you tend to manage to what you measure. In says that subjects in a setting will improve aspects of their behavior being experimentally measured simply in response to the fact that they are being studied.

7. Hotelling's Law

This is a product rule that says it's natural and rational for businesses to make their products as similar as possible. Even in the age of The Long Tail and mass customization on the Internet, Hotelling's Law still seems to hold for many situations. So while this is a holdover from the 20th century, it still seems to apply in today's online world because the similarity creates aggregation that tends to drive a network effect for the members of the segment as a whole.

8. Jakob's Law

Jakob's Law represents a fundamental understanding of how the network functions (again, Internet or intranet) as a delivery channel and social system. Simply put, it says "users spend most of their time on other sites", and so you must be there too. This has driven an explosion of design techniques to leverage this simple yet powerful truth in product distribution and social architecture to creation adoption and enable growth.

9. Kurtosis Risk

Kurtosis Risk occurs whenever " observations are spread in a wider fashion than the normal distribution entails". In other words, when there are a lot more outliers than normal measurements in your sampling of social data such as user behavior, architecture of participation, community analytics, or other key performance measurements. The Kurtosis Risk is also a form of The Long Tail, which has been know to cause any model to understate the risk of variables when they have high edge distribution. Infamously, this is what seemed to happened to hedge funds and other financial instruments as we headed into the down market as well. The key is that it can also happen to your social environment and its ROI, risk, and reward measurements.

10. The Long Tail

Coined by Chris Anderson, this well-known Web 2.0 buzzphrase refers to the ability to mass service micromarkets for very little cost. In other words, moving from providing best selling products to the full spectrum of offerings in the market, which is a larger, potentially more lucrative market overall, if you can service it cost effectively. While the actual data that formed the research into The Long Tail has been the bone of contention in recent years and has been revised and extended, it still represents an invaluable source of knowledge on how to design network-based systems, social and otherwise, for high efficiency and return.

11. Metcalfe's Law

This was the original conception of network effects, whereby the potential value of a network grows exponentially according to its size. It is one of the original power laws in technology and, although subject to substitutions with newer formulations and some criticism, it is still widely cited. Metcalfe's Law holds true of anything that has a network structure, including telephone networks, computer networks, social networks, etc.

12. Moore's Law

Intel founder Gordon Moore, back in the early days of the industry, noted that computing power doubles every eighteen months. This has largely held true for decades and looks now like it will hold up well for at least some time longer. However, the speed and capacity of storage and communication networks has greatly exceeded Moore's Law for quite some time now and consequently is driving dislocation in many traditional computing models where processing power used to dominate. Not only is this making distributed computing more attractive and making new techniques possible, the fact that computing hasn't kept up with the network ensures that the network will continue to dominate as a growth engine in terms of it's overall ability to deliver real business value. The fundamental (and slightly oversimplified) implication is that business models tied to computing can't compete with business models that are tied to communication, which as we'll see with Reed's Law, is significant.

13. Network Effect

The fundamental definition of a network effect is "when a product or service has more value the more that other people have it too." Any system with value that can accumulate value through use has a network effect. Example: When someone buys a mobile phone, it makes the phone network all that much richer because of another person that can be reached or will make calls. The same is true when someone uploads a video to YouTube. The services with the strongest network effect (best data, largest community, etc) will grow faster. Michael Arrington famously said to startups that they shouldn't "fight an established network effect." It's just too expensive (recall that network effects are based on exponential power laws like Metcalfe's Law). But optimizing for what makes your service or social network special and unique will work, by creating a new submarket. Enterprise software is now experiencing the network effect of viral, Web 2.0 platforms, and I've seen numerous recurring instances of platforms such as MediaWiki pushing larger, established enterprise installations to the sides of their organizations through simple patterns such as "network effects by default." Note that this is also one of the core definitions of Web 2.0: "Networked products or services that explicitly leverage network effects."

14. The Pareto Principle

The Pareto Principle is the famous 80/20 rule or the principle of factor sparsity (I prefer the 80/20 rule.) It basically says that "roughly 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes." The Pareto Principle is also an illustration of a "Power law" relationship, which occurs often in natural phenomena such as brush-fires and earthquakes. Because it is holds true over a wide range of magnitudes, it produces outcomes completely different traditional prediction schemes. It has been claimed, for example, that it explains the frequent breakdowns of sophisticated financial instruments. This is also likely true of any complex system, including social ones, and increasingly social and community dynamics are seen as falling under this rule in numerous ways, from participation pyramids to abandonment rates.

15. Principle of Least Power

This seemingly arcane rule states that "given a choice among computer languages, classes of which range from descriptive to procedural, the less procedural, more descriptive the language one chooses, the more one can do with the data stored in that language." In practice, it has considerable implications for the knowledge economy. Data that is trapped in complex or obscure formats can't be searched or otherwise processed, and the success of the Web as a content medium has largely been responsible for giving this principle its credibility. HTML and SQL are good examples of this. Enterprises frequently ignore this principle at their peril and have been left with oceans of submerged data and knowledge.

16. Principle of Least Effort

Though it sounds simplistic, a surprising number of software and social systems ignore this rule, which says people basically vote with their feet to the easiest solution. In fact, the Principle of Least Effort notes that they will tend to use the most convenient method, in the least exacting way available, with interaction stopping as soon as minimally acceptable results are achieved. As a result, well-known social scientist Clay Shirky notes that the most "brutally simple" social model often is the most successful one (using Twitter as an example.)

17. Reed's Law

Researcher David Reed discovered that the network effect of social systems is much higher than would otherwise be expected, helping to explain the sudden rise of social systems in the latter half of this decade. While adding a social architecture to a piece of software for no specific reason isn't helpful either, it turns out that in general, software (and indeed, any networked system) is better the more social it is.

18. Reflexivity (The Social Theory)

Part of the conversation about the Hawthorn Effect, reflexivity refers to circular relationships between cause and effect. Reflexivity is important in explaining the tendency of social systems to move away from equilibrium and often towards extremes (flame wars, viral feedback loops, rapid information propagation, etc.) Reflexivity asserts that social actions can and do in fact influence the fundamental behavior of a social system and that these newly-influenced set of fundamentals can then proceed to change expectations, thus influencing new behavior. The process continues in a self-reinforcing pattern. Because the pattern is self-reinforcing, social systems can tend towards disequilibrium.

19. Sarnoff's Law

Another way to value the network, Sarnoff's Law, created to describe older one-way networks such as broadcast medium like TV or radio, says "the value of a broadcast network is proportional to the number of viewers." A more modern version of this is Beckstrom's Law, but its inclusion here is to show that if the network is the primary infrastructure that supports the knowledge economy, we still have a hard timing measuring it's true value. Sarnoff's Law is not invalidated in a Web 2.0 world as services such as Compete.com and Web analytics demonstrate. Again, the lessons of Sarnoff's Law are frequently less-than-appreciated inside of many enterprises (though marketing departments often do make use of them.)

20. The Taleb Distribution

The Taleb Distribution is a probability distribution where there is a high likelihood of a small gain combined with a small probability of a very large loss, which would more than outweighs any gain. The term is now used to describe dangerous or flawed investment strategies. The attractiveness of Taleb Distribution scenarios is the illusion of steady returns until there is sudden catastrophic loss. The Tabel Distribution is interesting to the social economy for the same reasons as Kurtosis Risk: It can make social business options such as crowdsourcing and other open business models more balanced when looked at in this light because it can appropriately highlight the lack of predictability and identify unacceptable risk profiles.

21. The Thomas Theorem

The Thomas Theorem identifies a trend that is particularly common within social worlds that any definition of the situation will influence the present. The theorem stresses social situations including in family, business, or other life as fundamental to the role of the participant when mentally creating a social world "in which subjective impressions can be projected on to life and thereby become real to projectors." This is how social worlds, on a network or otherwise, can take on a life of their own. The reputation and standing of individuals as they perceived on networks, is often very different from what they have in real life. This has implications for HR, promotions, rewards, and motivations in enterprise social computing environments.

22. The Tinkerbell Effect

We wrap this list up with a slightly humorous restating of an aspect of The Thomas Theorem. The Tinkerbell Effect, in essence, posits that:

Those things that exist only because people believe in them. The effect is named for Tinker Bell, the fairy in the play Peter Pan who is revived from near death by the belief of the audience.

Contribute Your Social Laws in Talkback Below

Of course, this list is only representative of the many things we know about networked systems and social computing currently. Please leave your own contributions in Talkback below and I'll highlight the best here with updates.

Which of these power laws are you seeing take place in your organizations?