Computing's low-cost, Cloud-centric future is not Science Fiction

In early 2009 I wrote an article called "I've seen the future of computing: It's a screen." It was a an almost Sci-Fi sort of peice, projecting what I thought the personal computing experience might resemble ten years into the future, in 2019, based on the latest industry trends at the time. It was the second of such pieces, the first of which I wrote in 2008.

In May of 2011 I also wrote another speculative piece about what I thought personal computers would be like in the year 2019.

Late last year, I imagined another speculative and futuristic scene, portraying the shift towards ecommerce and the fall of brick and mortar retail shopping.

Futurist thought exercises such as these are always fun, but inevitably, with any sort of long-range predictions of the future, there are things which are very easy to miss and get so wrong that you fall flat on your face. Futurism never gets everything right, but sometimes it can also be dead-on and flat out uncanny in its accuracy.

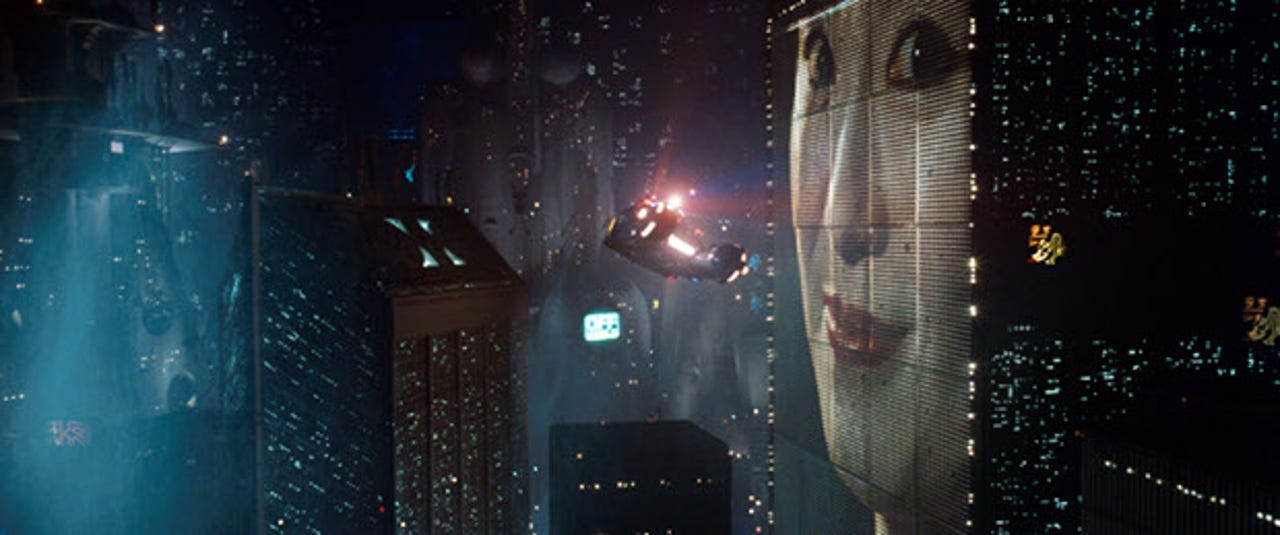

Excellent examples of these complete miss and "holy crap, were they right!" type of predictions can be found in classic Sci-Fi movies like Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Ridley Scott's Blade Runner (1982).

In 2001, Kubrick is way ahead of his time in his depictions of manned and commercial space travel and the colonization of the moon, as well as true artificial intelligence, things which are probably at least several decades away. Still, the technologies to accomplish such feats are definitely within our reach if the world's governments can cooperate and establish clear goals to achieve them.

But in 2001, Kubrick also shows working tablet computers as well as personal video conferencing, technologies which have only recently become more commonplace. In 1968, when the film was first released, the forerunner to the Internet, ARPANET was still being developed at the US Department of Defense, so the concept of a world wide connected computer network that was accessible to the average Joe, let alone the military or academia was not yet a part of the common Sci-Fi vernacular.

Scott's Blade Runner, like Kubrick's 2001, is also very much ahead of its time. Dystopian Futurism is one of the huge themes of the film, depicting flying cars, giant overpopulated and polluted cities with towering 100 story buildings, and genetic engineering gone out of control. 30 years after the film's release, it is still considered to be a SF masterpiece.

We don't have flying cars yet. However, personal computers and mobile devices are everywhere in 2012, something we see a lot of in Blade Runner. And yet, the entire concept of PCs and an entire industry dedicated to them was brand new when the screenplay was in development and being filmed.

And while we don't have the ability to create genetically engineered, custom-made "replicants" of animals and human beings as it is depicted in the movie, life sciences have made tremendous advancements since the film was first released, such as the ability to map the human genome and create genetically modified organisms for commercial use. The cloning of plants and some animals is now common practice in modern agribusiness.

The massive influence of globalization, Japanese culture and its multinational corporations in Blade Runner on American society is a huge part of the film's futurism, and is something that we take very much for granted today.

Little did we know in 1982 when that film was released that not only would Japan surpass the United States as a producer of electronic goods, but in 30 years, it would eventualy cede its position as the world's most dominant producer of technology to China, Korea and other Asian as well as South American countries.

My 2009 "It's a Screen" article describes a future centered around the Cloud, server-based computing, virtualization, low-power and low-cost ARM-based devices. The iPhone's App Store at the time was a less than a year old and Android was only beginning to gain market traction with the recent release of the Motorola Droid on Verizon. The iPad was a year away and certainly, there were no Android tablets.

In 2009, the idea of consumer driven Cloud-based content consumption and data storage was still very much in its infancy. At the end of 2012, we now have our choice of Cloud content and storage providers with Google, Apple, Amazon and now Microsoft, with the launch of Windows 8, Windows Phone 8, Windows RT and the Windows Store.

In 2009 the Chrome browser itself was less than a year old, and the idea of a Chromebook was probably just a twinkle in Google's eye.

This week, Google and Samsung released a new $250 version of the Chromebook. There's not much new or even innovative about this particular device, particularly from a UX standpoint -- it's the same Chrome OS we've seen before, except that it now runs on very inexpensive, ARM-based hardware.

Also Read:

- The Google Chromebook, Suddenly is an Enterprise Contender (Eric Lai)

- Will a Chromebook be your next PC? (Steven J. Vaughn-Nichols)

- New Samsung Chromebook, ARM processor and $249 (James Kendrick)

So it's understandable that a lot of prominent tech industry bloggers have received this with a yawn, especially since we're only a few days away from the likely introduction of the iPad Mini, as well as Microsoft's Windows 8 OS and Windows RT tablets, not to mention another Google Android event which is rumored to be the launch of several new Nexus-branded Android devices.

Granted, theres a lot more sexy and pure "wow" factor in these devices than the new Chromebook.

But that doesn't make the launch of the new Chromebook any less important than a newer, smaller iPad or the next generation of Microsoft's OS.

The significance of this particlular product release isn't about UX and Apps. It's about bringing down the cost of of computing down to affordable, almost disposable levels, and leveraging the Cloud to do the heavy lifting which we've otherwise relied upon much more powerful personal computers to do before.

For the past 30 years, the driving force behind personal computing been Moore's law -- the quest to double microprocessor density and performance every 12-18 months.

What the Chromebook truly represents is moving away from Moore's Law as the key metric in the development of personal computing.

While the price of personal computers in the last 30 years has gone down substantially, and they have become exponentially more powerful, they are still considered to be expensive and inaccessible to many people, particularly in poor urban and rural population centers in the United States, other parts of the Western world, as well as in developing countries.

They are also prone to quick obsolescence, require regular software maintenance, can be expensive to repair and require considerable support infrastructure. And with the state of the current world economy the quality and longevity and reliability of computer components has also declined substantially. To use the old adage, they definitely "don't make them like they used to."

So what the Chromebook truly represents is moving away from Moore's Law as the key metric in the development of personal computing.

Instead of doubling processor speed on a yearly basis as the prime goal of the semiconductor industry, we're going to see processor and component integration increase on a yearly basis, moving away from expensive laptops and desktops with many components requiring complex and expensive manufacturing processes to single-chip systems which are are much more power efficient, cheaper to produce and cost under $300 retail.

That Samsung can produce the new Chromebook, using its own processor foundries, its very own manufactured RAM and flash storage and is own display technology is a massive vertical integration achievement in and of itself and should not be ignored.

It's something that even Apple, which is a veritable master of supply chain managment, still does not have the capability to do.

So what will computing's future really look like in 2019? Who will be the leaders and what will be the predominant platform? I'm not going to say that it's going to be Apple, Google, Microsoft, or some other player which may emerge. From a platform standpoint, the playing field is still wide open. It would not surprise me at all if every single one of those companies carves out a distinctive niche for their respective ecosystems, acting as feudal lords over their Cloud estates.

What I can tell you is that the rules have changed, and the balance of power has shifted -- to empower the user, in a far cheaper, much more ubiquitous and much more centralized way than we ever imagined.