Do Not Track gets support in iOS 6, but patent woes loom

When Firefox introduced Do Not Track as a browser feature, Mozilla put out a press release and built a detailed FAQ.

Microsoft published multiple blog posts by the company’s Chief Privacy Officer to defend the decision to enable Do Not Track in Internet Explorer 10. The company even built a comprehensive multi-browser test page.

Google told CNET’s Stephen Shankland earlier this year that Chrome would support Do Not Track “by the end of the year,” presumably meaning 2012.

Apple’s Safari page boasts that “Safari takes your privacy seriously. You can turn on Do Not Track, an emerging privacy standard.” That option debuted in Safari 6 on OS X, where the settings are exactly where you would expect them: on the Privacy tab of the Options dialog box, labeled “Ask websites not to track me.”

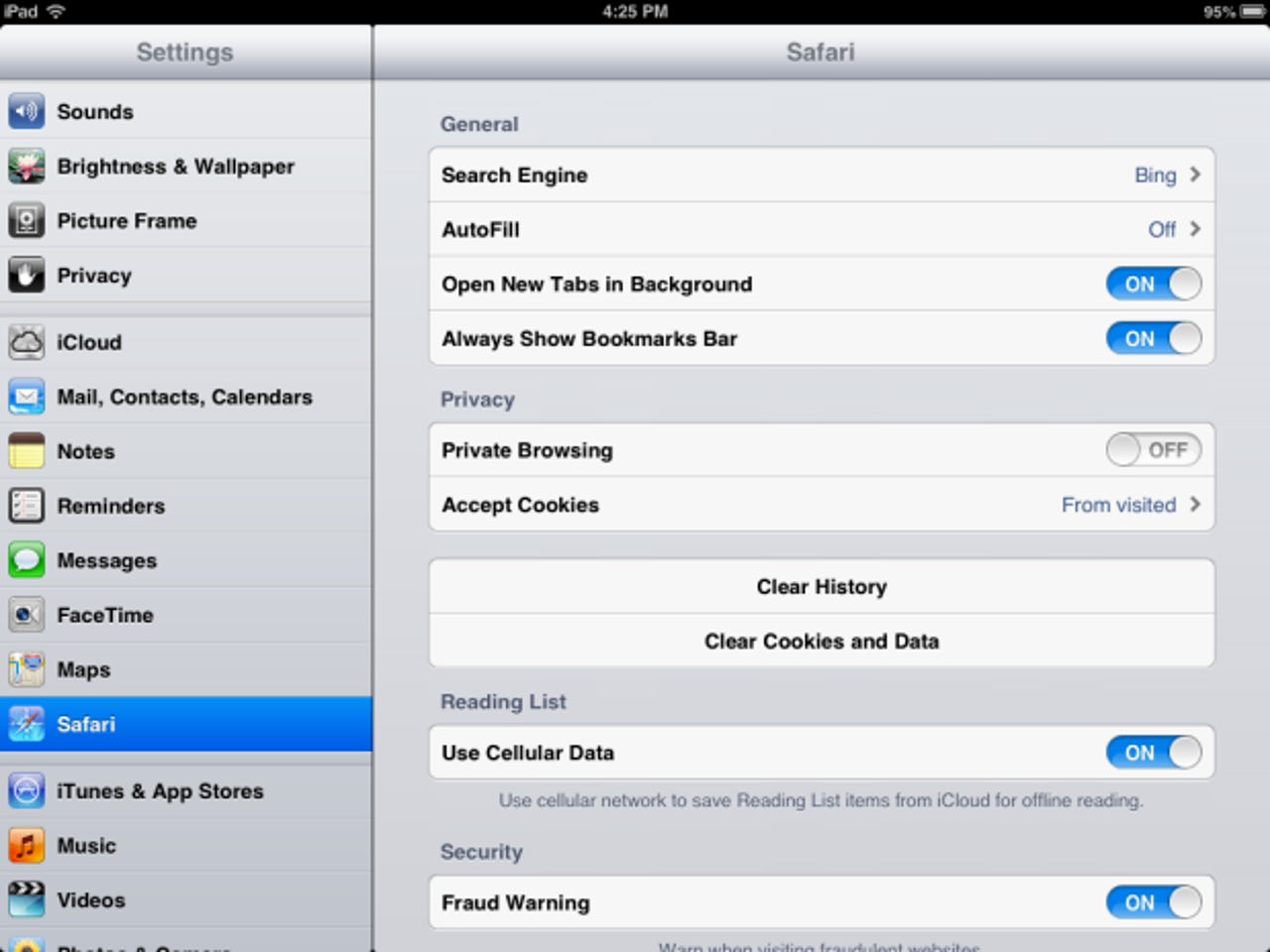

So what about Safari in iOS 6? I can’t find any official indication from Apple that the mobile browser supports DNT. If you open Settings and tap Safari on an iPad, there’s nothing that mentions tracking—just this switch that lets you toggle something called Private Browsing (which is off by default).

And would you believe it? Flipping that switch adds the DNT:1 header to every Safari request, as confirmed by a visit to a DNT test page set up by 3PMobile (description here, actual test page here).

Technically, that may be a violation of the Tracking Preference Expression (DNT) standard, at least as embodied in the current draft by the W3C working group. The section headed “Determining User Preference” makes it clear: “[That] expression … MUST reflect the user's preference, not the choice of some vendor, institution, or network-imposed mechanism outside the user's control. The basic principle is that a tracking preference expression is only transmitted when it reflects a deliberate choice by the user.”

There’s a “Private Browsing” option on the OS X version of Safari, which discards cookies but doesn’t enable DNT. And I can’t find any documentation of this iOS behavior, which is decidedly different. Without that documentation, it's hard to argue that a user would know that sliding that switch sends out the DNT header.

The advertising industry threw an epic hissy fit over Microsoft’s decision to make Do Not Track the default setting when users set up Windows 8 for the first time. In that case, though, the “Do Not Track” language is called out clearly in the consent dialog box, and users have to agree to accept that setting.

Peter Cranstone, CEO of 3PMobile, is the one who first discovered this behavior. It shouldn’t be surprising that he pays close attention to this issue, because his company has a very big dog in this hunt. That dog is U.S. Patent number 8,156,206, whose claims include this one:

A computer-implemented method comprising: providing an end user of an Internet-enabled device with an ability to selectively enable a current web browser privacy setting from among a plurality of web browser privacy settings by presenting a user interface containing options regarding the plurality of web browser privacy settings to the end user via a display of the Internet-enabled device; receiving, by a web browser running on the Internet-enabled device, a navigation request relating to a web server; responsive to the navigation request, causing a HyperText Transport Protocol (HTTP) request to be generated, wherein a value associated with an HTTP header field of the HTTP request is set based on the current web browser privacy setting; and directing the web server to return to the web browser content associated with the navigation request tailored in accordance with the current web browser privacy setting by transmitting the HTTP request to the web server.

That’s essentially a description of the Do Not Track header. Mozilla dismissed it as a “false patent claim.” But the W3C has taken Cranstone’s complaints seriously enough to convene a Patent Advisory Group (PAG), with this reason listed in the opening “Goals” section:

The mission of this Patent Advisory Group is to study issues and propose solutions related to the Tracking Preference Expression Working Draft. An outside party (who is contributing postings to the Working Group mailing list) has been alerting articipants [sic] in the Working Group about his US Patent Nr. 8,156,206. Some of these communications were at time disruptive to the conversations of the Working Group, and have been the reason for serious concern among participants in the Working Group.

Forming a PAG has the potential to grind the standards-setting process to a halt. Cranstone says he has offered a royalty-free license for the patent to Mozilla and the W3C, but both have rejected the offer.

It’s hard to tell whether the possible patent squabble is a speed bump, a pothole, or a massive sinkhole that will swallow the nascent Do Not Track standard completely. Whatever the cause, the ratification of the standard has been pushed from the end of this year to sometime in 2013.

A meeting of the W3C working group in Amsterdam concluded yesterday. It remains to be seen whether that meeting will result in a smooth resolution of outstanding issues, a hardening of competing positions, or just more foot-dragging and bickering.