Government urges industry piracy code under new regulations

Australia's carriage service providers (CSPs) have been asked by the federal government to voluntarily help develop a code for online access to copyright content under new draft regulations.

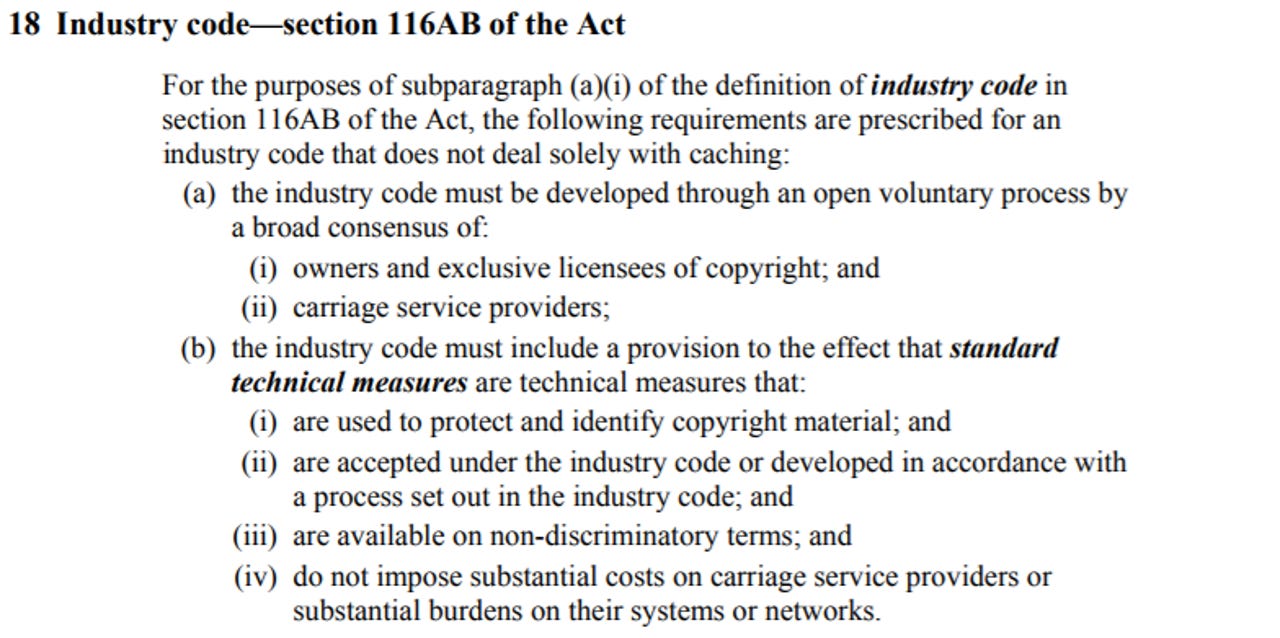

Under Section 18 of the Copyright Regulations 2017 exposure draft [PDF], released this week, an industry code that does not deal solely with caching "must be developed through an open voluntary process by a broad consensus of owners and exclusive licensees of copyright and carriage service providers".

The code must include a provision where standard technical measures are used to protect and identify copyright content; are available on non-discriminatory terms; and do not impose substantial costs on carriage service providers or "substantial burdens on their systems or networks".

The consultation paper [PDF] added that the code should also ensure that CSPs accommodate and do not interfere with "technology used at the originating site to obtain information about the use of the copyright material" and comply with provisions relating to updating cached copyright material.

An industry code is defined under the Copyright Act 1968 as being a code that meets prescribed requirements and is registered under the Telecommunications Act 1997, or "an industry code developed in accordance with the regulations", while caching is described as "the reproduction of copyright material on a system or network controlled or operated by or for a carriage service provider in response to an action by a user in order to facilitate efficient access to that material".

The government is consulting with industry on whether the requirements in the proposed new s18 are appropriate, and is asking what procedure the Copyright Regulations 2017 should prescribe for the development of an industry code.

"The Copyright Regulations 1969 do not currently set out prescribed requirements for an industry code ... the department would welcome suggestions on the requirements the proposed new regulations should prescribe, if any, for industry codes," the consultation paper says.

According to the paper, if the regulations stipulated a procedure for developing a code, "industry could be more inclined" to develop it.

"The Copyright Regulations 2017 present an opportunity to provide the procedure that must be followed to develop an industry code," the paper says.

"The department would welcome suggestions on the mechanism the new regulations should prescribe for the development of an industry code for this purpose."

A similar three-strikes piracy code was abandoned by industry last year after disputes between CSPs and rights holders over who should bear the cost.

Both the Copyright Regulations 1969 and the Copyright Tribunal (Procedure) Regulations 1969 are currently being rewritten by government before they sunset on April 1, 2018, with the Department of Communications saying it must ensure regulations are "fit for purpose in the digital environment".

"This is the first time these copyright laws have been reviewed since they were introduced," the department said.

"They are complex and no longer reflect the way people, organisations, and the Copyright Tribunal operate in Australia. The new legislation must be fit for purpose, reflect modern language and practices, and reduce red tape."

The draft Copyright Regulations have also come up with a series of principles dealing with the requirement in s116AH of the Copyright Act that CSPs must adopt and implement a policy providing for the termination of repeat infringers' accounts.

Under s24(1) of the draft Copyright Regulations, the owner or exclusive licensee of the content can give a notice of infringement to a CSP, which would then pass this on to the alleged infringer. Under s25, the CSP must then "expeditiously remove or disable access to" such copyright material, and notify the user that it has done so (s30).

If an owner finds that copyright material is being hosted, it can notify the CSP (s34), which the CSP must then remove (s35).

The Federal Court of Australia has been working through a similar regime, last month ordering CSPs to block over 160 alleged piracy sites after s115A of the Copyright Amendment (Online Infringement) Act, which passed both houses of Parliament in mid-2015, allowed rights holders to obtain a court order to block websites hosted overseas that are deemed to exist for the primary purpose of infringing or facilitating infringement of copyright.

The proposed Copyright Regulations have said a user may dispute the removal of the alleged copyright material via a counter-notice within three months (s26), however, with a copy of this to be sent by the CSP to the copyright owner (s27).

Section 28 then says that if a copyright owner does not respond to the counter-notice within 10 business days, the CSP must restore or enable access to the material on its network. If a CSP fails to restore access, it may itself be liable to civil remedies and damages under s38.

Acts subject to receiving an infringement notice (s42) include making infringing copies of copyright material commercially; selling, hiring, or distributing copies or offering to do so; exhibiting copies in public; importing copies commercially; commercially possessing copies; building a device for the purpose of making copies; and removing or altering electronic rights information from copies.

An infringement notice must be distributed within 12 months of the alleged offence (s43(3)) and must relate only to a single offence (s43(4)).

According to Section 44, the amount payable under an infringement notice is 12 penalty units for individuals or 60 penalty units for corporations, to be paid within 28 days -- although this window can be extended (s45) or the notice withdrawn (s46) via application by the user to the relevant CEO -- or risk facing prosecution.

With one federal penalty unit equal to AU$210, the fines would be around AU$2,520 for individuals or AU$12,600 for corporations for each offence.

The new Copyright Regulations would also provide an alternative to being prosecuted under s41 as long as they pay the Commonwealth the amount specified in the infringement notice; forfeit to the Commonwealth any infringing copies; and forfeit to the Commonwealth the device -- such as a computer program -- used for making the copy.

Paying the fine is not an admission of guilt or liability, according to s47, and means that person or entity cannot be prosecuted for the alleged offence; however, if prosecuted, the court may use its own discretion to determine the amount of a penalty (s48).

The penalty amount specified follows the Australian Federal Court ruling that copyright owner Dallas Buyers Club (DBC) would not be permitted to seek damages from alleged copyright infringers because it had sought "untenable" amounts.

DBC abandoned its case after the court said it would be allowed to send letters seeking damages from those who allegedly infringed as long as it only sought compensation based on the retail price of the film and the costs associated with obtaining each infringer's details -- instead of DBC's preferred additional damages based on a one-off rental fee and a licence fee for uploading activity.

The new Copyright Regulations also state that copyright has not been infringed (s40) when works are reproduced, copied, or communicated by a library, archive, person with a disability, or educational institution; under s16, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Australian National University, and Special Broadcasting Service are considered bodies that administer key cultural institutions, while the Crown is also able to use material under s121.

Section 40 also provides a "fair dealing" provision for research, study, criticism, review, parody, or satire when it is done by a student for the purposes of research or completing a course at an educational institution.

The exposure draft of the Copyright Legislation Amendment (Technological Protection Measures) Regulations 2017 [PDF], meanwhile, repeals much of the previous regulations and updates exemptions allowing people to bypass "technological protection measures" (TPMs) including software controlling access to copyright content.

"Due to the complexity in the regulation-making power for new exceptions that allow users to circumvent TPMs which restrict access to, or sharing, of copyright material, these will be updated," the consultation paper says after the government had last month flagged that it would be looking to update TPM provisions during the second half of 2017.

The proposed Copyright Regulations are open to consultation on whether they are fit for purpose or could be simplified or modernised further until October 6.

"The department is not seeking views on whether substantial policy changes should be made to the provisions in the exposure drafts," it clarified.

Instead, it is seeking comment on such issues as the prescribed fair dealing provisions in s40; and whether the infringement notice scheme is "still necessary".

While the government has been looking to update its copyright laws, its response to intellectual property provisions in August merely "noted" recommendations by the Productivity Commission concerning circumventing geoblocking technology and implementing a fair use exception for copyright infringement, and supported "in principle" an expansion of the safe harbour scheme to cover all providers of online services, including cloud, search engines, and online bulletin boards, rather than just CSPs.

The government passed digital fair dealing as part of the Copyright Amendment (Disability Access and Other Measures) Bill 2017 in June, making provisions for access to copyright material by those with a disability, along with protecting educational facilities, key cultural institutions, libraries, and archives from copyright infringement.