We're not ready for the impact of generative AI on elections

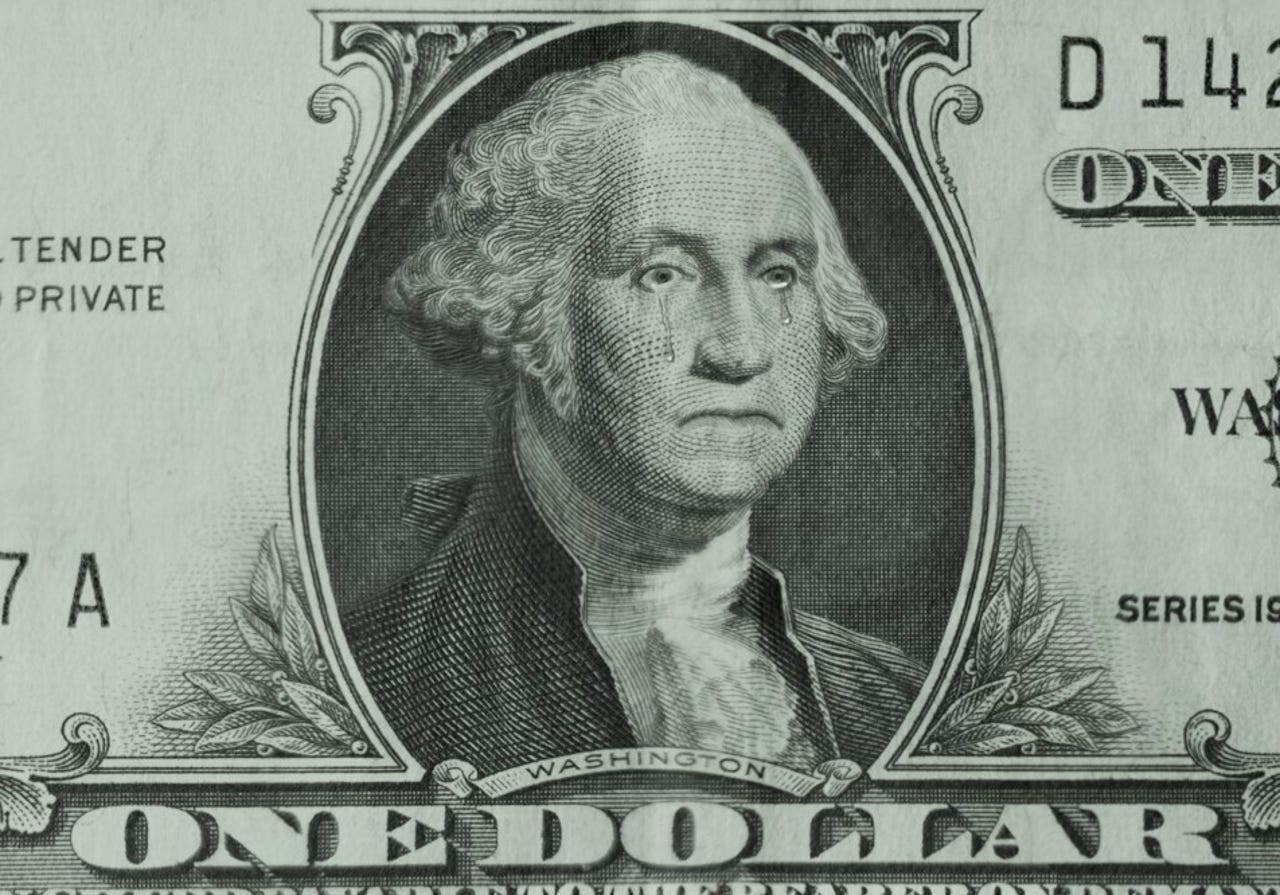

Does all this make you want to cry? Well, George Washington wept here too.

Have you heard the one about George Washington not supporting the Revolutionary War?

While serving as a general leading the rebel forces, George Washington was convinced the American War of Independence was a mistake. He was "far from being sure that we deserve to succeed."

Also: How I tricked ChatGPT into telling me lies

In 1777, a soldier serving under British General Oliver De Lancey found a trunk belonging to General Washington. The trunk contained a series of letters in Washington's own hand that told of his desire for reconciliation with England and even, "I love my king."

The trunk was found in the hands of Washington's valet (and enslaved person) William Lee, when Lee was captured by the British.

Here was tangible proof that even Washington himself didn't support the war.

Years later, in 1795 when Washington was petitioning the Senate to ratify the Jay Treaty with France, the letters were cited as evidence that Washington's loyalty couldn't be trusted and that he didn't really care about democracy. It made passing the Jay Treaty very difficult.

Except… William Lee was never captured by the British. In fact, William Lee never left Washington's side during the Revolutionary War. The letters were carefully crafted forgeries, the 18th-century equivalent of deepfakes.

Also: Just how big is this new generative AI? Think internet-level disruption

They haunted Washington so much that he penned -- as one of his last acts in office -- a rebuttal of the forgeries in a letter to US Secretary of State Timothy Pickering.

From George Washington to Washington, DC

Fast forward to 2018. I'm about to touch on topics that are politically charged. For a moment, please ignore the politics, and focus on these as examples of the existence of disinformation. That's the topic of this article. Disinformation hurts all parties. But in order to show you what's been happening, I have to cite real examples. And that means I have to mention politicians.

So here we go…

Example 1: Kremlin-backed disinformation campaign

The House Intelligence Committee, investigating the 2016 presidential election, posted a library of more than 3,500 ads containing fake claims designed to disrupt the American political system.

The ads were produced and purchased by a Kremlin-backed troll farm between 2015 and 2017. In addition to the purchased ads, the House Intelligence Committee stated that there were at least "80,000 pieces of organic" social media content produced by Russian interests.

Example 2: Modified video faking drunken behavior

Next, we're going to stop in 2019 to look at a video that showed then Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi slurring her words and appearing drunk. This was from a video of Pelosi giving a speech at a Center for American Progress (a liberal-leaning "think tank") event.

The video, shared on Facebook more than 45,000 times and hosting more than 23,000 comments, was a fake. The original video had been edited to "make her voice sound garbled and warped" and to make her appear inebriated.

The weaponization of generative AI in political campaigns

Photos, videos, audio, and even hand-written letters have all been faked over the years in the service of political dirty tricks. While they varied in quality based on the skills of the forgers, the practice is nothing new.

Also: How does ChatGPT actually work?

Keep that in mind as we move forward to a discussion of deepfakes in the time of generative AI. Peggy Noonan, who in a previous life was the lead speechwriter for President Ronald Reagan, wrote this in her Wall Street Journal column:

At almost every gathering, artificial intelligence came up. I'd say people are approaching AI with a free floating dread leavened by a pragmatic commitment to make the best of it, see what it can do to make life better. It can't be stopped any more than you can stop the tide. There's a sense of, "It may break cancer's deepest codes," combined with, "It may turn on us and get us nuked."

That about sums it up. As Noonan travels in rarified political circles, this statement is evidence that even the political upper crust regards generative AI with a sense of concern.

That, of course, does not stop them from using the technology to their advantage.

Last month, supporters of Ron DeSantis, the governor of Florida and the Republican presidential candidate currently ranked in the #2 position based on polling data, used an AI-generated voice to imitate President Trump in an ad that made it appear the former Republican President was attacking Republicans.

Also: How to make ChatGPT provide sources and citations

To be clear, the words spoken by the AI were based on a real post by Trump on the Truth Social social media network. The ad was funded by the Never Back Down PAC, which is technically not affiliated with Governor DeSantis. However, the PAC is heavily backing DeSantis. Presumably, the PAC felt that using the former president's voice with his own words would be more effective or realistic than an announcer speaking them in a voice-over.

In another ad attributed to DeSantis, President Trump is shown hugging Dr. Anthony Fauci. This was an AI-generated image. Fauci is a former member of Trump's Coronavirus Task Force, former Chief Medical Advisor to the President, and -- for almost 40 years -- Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Fauci, as most well know, became a divisive figure in the early days of the pandemic. The DeSantis campaign apparently was trying to link Trump to Fauci for political gain.

The purpose of this article isn't to debate the content of political ads. Instead, it's to focus on the use of AI and what it means going forward. The images of Mr. Trump hugging Dr. Fauci were notable because they were AI-generated.

In March, The New York Times described how the Democratic Party was testing the use of AI for drafting fund-raising messages, with "appeals that often perform better than those written entirely by human beings."

Also: How researchers broke ChatGPT and what it could mean for future AI development

The Times also reported on faked images broadcast on social media that showed President Trump being arrested in New York City.

While AI could definitely prove to be a force multiplier for national elections, I expect it to be used heavily in campaigns where lower budgets require more creative use of resources. One such campaign, as reported in the Insider, was for Mayor of Toronto. The Insider shared an image from a campaign flyer produced on behalf of candidate Anthony Furey that showed a woman with three arms.

When I looked online at the circular cited by The Insider, it did not have the picture they showed in the article. I'm guessing that mistake was corrected by Furey or his campaign team. Regardless, Furey lost, coming in fourth, with just barely more than 10% of the votes received by the winner.

So, while AI may help create fake imagery or reduce costs, it doesn't guarantee a win. Nothing does.

What does it all mean?

Just because a campaign is using generative AI doesn't mean it's weaponizing it. There are four main categories of use for generative AI tools in campaigns, and only one is solely negative in nature.

Deepfakes and forgeries: This is the one that's the most potentially destructive. Any time a campaign fakes information, it's destructive and falls into the dirty tricks category. What makes this more troubling now is that the AIs make generating fake imagery possible for a lot more people, so we're likely to see this more often -- and not just from campaigns.

Also: 6 things ChatGPT can't do (and another 20 it refuses to do)

Helping compose ads and letters: Expect to see AI helping campaign staff compose ads and letters. While the content may contain falsehoods or misrepresentations, that's nothing new. Campaign workers were bending the truth in written documents long before the advent of generative AI.

Increasing the speed and customization of content for mass outreach: The most effective campaigns often have deep databases on prospective voters, especially prospective donors. They buy lists, aggregate data from previous campaigns and other candidates, and attempt to build profiles that help precisely target prospects. Expect generative AI to be used to individually calibrate outreach efforts to each prospect, and do so en masse.

Performing trend and sentiment analysis looking for insights: In a previous article, I showed how powerful AI can be when data mining for insights. Campaigns have often used enterprise-level data mining software, but expect the power, ease of use, and comparatively low price of tools like ChatGPT Plus with Code Interpreter to make these capabilities available at all levels of campaigns.

Also: I asked ChatGPT, Bing, and Bard what worries them. Google's AI went Terminator on me

Lawrence Pingree, Gartner's vice president of emerging technologies and trends - security, added some insights on this topic. He told ZDNET:

I think the biggest new danger is that Generative AI large language models can now be instrumented with automation. That automation (examples - AutoGPT, BabyAGI) can be used to do goal-oriented misinformation campaigns.

This makes it much easier for both political parties or nation states to carry out influence operations.

LLMs also can be paired with deepfake technologies to run campaigns that can even potentially do audio and video. Taken to social media, these types of tools can create a very difficult digital environment for voters who want to know the truth.

When looking at generative AI in campaigns, the real impact will be outside presidential campaigns. After all, presidential campaigns have big money.

According to the Federal Election Commission, "Presidential candidates raised and spent $4.1 billion in the 24 months of the 2019-2020 election cycle." According to Open Secrets, which tracks election spending, the average winning US Senate candidate spent $15.7 million, while the average House candidate spent $2 million in the 2018 elections.

Some local campaigns have comparatively large campaign budgets. For example, looking forward to the 2024 elections for Los Angeles City Council and Los Angeles Unified School District, District 2 City Council candidate Adrin Nazarian has already raised $432,000, while LAUSD District 3 candidate Janie Dam has already raised $38,000.

Now, keep in mind that LA District 2 had a 2020 population of 793,342 people. Overall, LA County itself has a population of 9.7 million people. By contrast, the small historic rural town I live in here in Oregon has a population of less than 10,000 people.

Also: Real-time deepfake detection: How Intel Labs uses AI to fight misinformation

Smaller campaigns, especially campaigns in towns the size of mine, have much smaller war chests than the national campaigns. Generative AI tools can give even the smallest campaigns analytics tools previously only available to campaigns with six- and seven-figure budgets.

So while we can certainly expect presidential campaigns to use AI to put opposing candidates into compromising positions (or, at least, portray them in a way red-meat supporters would choose to share over social media), expect to see the biggest impact of generative AI far down the ticket.

Also: Google to require political ads to reveal if they're AI-generated

As, at least something of a defense against an onslaught of AI-generated ads, Google is now requiring AI-generated ads to include a disclaimer stating the ads were produced by synthetic means. Of course, that doesn't mean that rogue promoters will follow those directions. We'll still most likely see dump-and-run strategies by political operatives and enemy agents posting thousands of AI-generated ads without disclaimers, then moving on to new accounts, effectively bypassing Google's requirements through the use of speed and agility. Welcome to yet another arms race.

Stay tuned, because while campaign dirty tricks have been around forever, we're bound to see more of them now that everyone has access to the tools that make it absurdly easy to perpetrate them

Does all this make you want to cry? Well, remember: George Washington wept here.

You can follow my day-to-day project updates on social media. Be sure to subscribe to my weekly update newsletter on Substack, and follow me on Twitter at @DavidGewirtz, on Facebook at Facebook.com/DavidGewirtz, on Instagram at Instagram.com/DavidGewirtz, and on YouTube at YouTube.com/DavidGewirtzTV.