'EvoGrid' to model life's origins, and maybe answer the big questions

EvoGrid is a grid-computing concept that'll attempt to digitally simulate the primordial soup from which life arose and it may shed light on the origins of life on Earth and in the universe. It may also provide new tools for evolutionary biology, biochemistry, and complexity studies.

Studying the Earth's rocks, scientists know that life appeared on Earth roughly four billion years ago. They also tell us that for about a billion years before the first discernible life form snapped into existence, the Earth's environment was a pre-biotic chemical soup. But the conditions and forces present when life began are not that well-understood.

Now, using the power of computer processing, a group of international advisors and Bruce Damer, the founder of a research company that creates 3-D spacecraft and mission simulations for NASA and the space community, are utilizing a large interconnected grid of computers which could plausibly model the primordial soup.

Space.com reports that Damer and his chief architect, Peter Newman, are developing the EvoGrid concept by adapting GROMACS, a powerful open source molecular dynamics simulator originally developed at The University of Groningen in the Netherlands."We will be constructing a model of a 'toy universe', which has approximate properties of the early oceans on Earth," says Damer.

The simulation would work by first taking a list of basic physical properties entered into starting parameters, and allowing for artificial nature to take its course. Like the interactions and connections that took place between particles in the Earth's chemical oceans eons ago, the virtual particles would theoretically intermix into ever higher levels of complexity. It will use a level testing function that searches for emergent complex self-organization within the discrete element system of the simulation. The approach will focus computing resources and tuning parameters in order to permit the system to drive itself towards ever more complex emergent structures and processes.

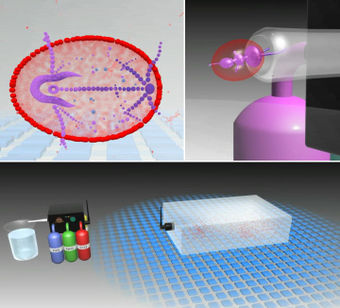

(Below is a collage of image stills from two movies that show where EvoGrid may take us years in the future):

The Space.com article points that the grid aspect of the project will be akin to SETI@home's screen saver, which enables computers at home to search for signals of extraterrestrial life within volumes of astrophysical data. "The Evogrid is conceived to have volunteer computers become part of an interconnected grid for maximum processing capacity. Damer hopes to eventually get a million computers hooked into the grid." But rather than showing a visualization of the entire system to each user, data processing limitations would give each user a view of the piece that their computer is handling.

"These computers would receive data from the EvoGrid simulation engine. The simulation would essentially consist of a vast virtual ocean of interacting numbers that would model the time before complex life forms emerged. To know whether self-organization is occurring, the program would look for persistent patterns within the data."

Damer and team note that even if EvoGrid generates some virtual but convincing life forms, either through random or directed means, "the numbers will always be numbers." But Damer hopes that someday the creatures generated by the Evogrid could be re-created chemically, not an entirely outrageous idea considering the effort underway to recreate all the biochemical steps necessary to synthesize a kind of proto-life in the lab.

Peering into the future, Damer and proponents of the project believe that harnessing the power of evolution is the way to solve difficult problems such as creating habitable zones to colonize. And by combining digital simulation and ever-increasing computing power to pave the way from science-fiction to reality:

Looking even farther into the future, Damer thinks that far more advanced EvoGrids, paired with "ChemoGrids", could be used to create a new genesis of cyber-physical life forms to colonize asteroids, or to terraform Mars into a more habitable planet for humans. Freeman Dyson, who is now an advisor for the EvoGrid project, popularized this concept, and Damer notes that "evolution within an adaptively-tuned living system is the only mechanism powerful enough to make a place outside of the Earth habitable for us."

Sources: Space.com, The EvoGrid Project