Malware boosting rise of cybercriminals

perspective Data leakage, fraud, identity theft, compromised confidentiality, impaired computing capabilities, financial loss, legal action, and damaged reputation--all of these have the potential to seriously undermine a business. And all can result directly from an inadvertent visit to a malware-infected Web site.

The number of malware-infected sites has grown at a startling pace. MessageLabs Intelligence estimates that Internet users worldwide now make over 100 million visits to malicious URLs every month. It's a genuine Web security pandemic.

But it's not only the sheer volume of Web threats that poses a danger. It is also the ever-growing guile with which they are devised and delivered.

Protecting your business is no longer simply a question of avoiding "dodgy" or unknown Web sites. Many mainstream sites are also being deliberately infected by cybercriminals with spyware, Trojans and other business-compromising malware waiting to be downloaded on visitors' machines.

Anatomy of an attack

Attackers conceal malware within a Web site simply to take control of visitors' computers. Once this is successfully achieved, the scope to exploit both the infected computer and its hapless owner is almost limitless.

Fundamentally, any Web-based attack comprises three key components--the set-up, the hit and the aftermath.

1. The set-up

First, the attackers decide exactly why they want to gain access to someone's computer, for example to steal sensitive data, or track browsing habits or keystrokes that could provide access to vital bank account passwords.Or they may want to recruit the machine to a botnet--a "robot network" of computers which, unknown to their owners, can be used by remote controllers to fire out spam or malware-propagating e-mail. The relevant malware is then obtained and placed on the Web--often on a newly registered domain which will at first be regarded with minimal suspicion.

2. The hit

Next, the attackers entice or compel potential victims to download the malware. For this to happen, of course, the victims first need to visit the infected Web site, which might occur in the course of their normal browsing behavior. Alternatively, they might be led there by adverts, links in spam e-mail messages, instant messages, social networking sites or blogs, "sponsored links" on Internet search engines or malicious links designed to appear high up on search engine results.If a machine is already infected, a further possibility is that results generated by major search engines will lead not to the Web site indicated but instead, to a malware-infected site.

In some cases, the victim then has to be lured into taking a particular action in order for the malware to be downloaded. Social engineering, scaremongering, empty promises and outright deception are some of the techniques employed to achieve the attacker's desired result.

Examples include:

- a "click here to install" button which purports to enable the victim to download important software updates

- a "you're infected--click here to remove the virus" pop-up alert

- malicious files placed in areas where the victim expects to download music, software, movies et cetera.

In other cases, however, no action on the part of the victim is required for the malware to download itself. Again, there is a wide variety of ways this can be achieved, such as:

- "drive-by downloads", where a concealed malware program automatically installs itself on a computer as a result of the user visiting the infected Web site

- exploitation of vulnerabilities in out-of-date software or plug-ins, where malicious content on a Web site could take advantage of vulnerabilities in the operating system, Web browser, multimedia players or other programs to download files to the victim's computer

- use of a "Web attack toolkit" housed on a malicious server linked to the visited Web page. These toolkits can assess the set-up and physical location of the victim's computer and then target it with the type of attack most likely to succeed in that particular case.

3. The aftermath

Once the malware has installed itself on the victim's machine, it proceeds to perform the tasks it was specifically designed to undertake. This may happen straightaway or the malware may lay dormant, ready to be activated at a later date in response to commands sent by the attacker or a third party to whom the attacker has sold control of the computer.Whatever the timescale involved, the downloaded program may collect personal data, open ports to allow the attacker further access to the infected computer, change registry values, start or stop services/processes, edit and move files, or modify e-mail, Web browser and other software settings.

Such actions will, in turn, open up a range of options for the attacker, who could, for instance:

- hold the victims to ransom by locking them out from their computer and demand cash in return for a password to unlock it

- recruit the computer to a botnet and use it to send spam, steal credit card data, perform distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, et cetera

- tell the victims their computers are infected (via "scareware") and then charge for downloading useless remedial software, or download more malware to the machine

- steal personal information, monitor activity and collect data such as passwords, e-mail addresses and bank details

- edit files so that visiting frequently browsed Web pages results in the victim being redirected to malicious Web sites

- hijack the clipboard and alter material which, when pasted later, for example onto a site with user-generated content, contains different information such as a malicious Web link.

No safe haven

Today, there are a lot of Web sites set up purely with malicious intent. These are commonly advertised to potential victims in spam, spIM (spam over Instant Messenger), blogs and social networking pages. But now, cybercriminals have become much more systematic and organized in the way they compromise legitimate Web sites as well, using increasingly sophisticated techniques to do so--and stoking up the danger level for anyone visiting the Web.

For instance, attackers can place malicious files on perfectly legitimate sites. Visitors to a legitimate site can also be redirected to another site where malware is embedded. Another option is for the attacker to add scripts to a legitimate site that then automatically download malicious files from elsewhere.

An even bolder technique is known as "clickjacking". Here, the attacker actually alters what happens when a button or link is clicked on, with malicious code being executed instead of the proper function.

It has now become comparatively easy for the bad guys to subvert reputable Web sites this way because today, many Web sites harness multiple media types, pulling--or being fed--information from many sources. Scripts, plug-ins, databases and other sites/servers may all contribute to a Web site's overall content and hence to the visitor's experience. Not all of them may necessarily be under the control of the site's owners.

In fact, a Web site can consist of 100 to 200 components. And it may only take one of these to be compromised for a visitor to end up downloading malware. Moreover, such a component could go unnoticed for quite some time.

There are many ways in which a cybercriminal can compromise a legitimate Web site. The main ones include:

- Structured query language (SQL) injection: Attackers probe databases behind Web sites to determine their structure or obtain login credentials, the database is then updated or new records inserted, and Web page content is changed

- Using stolen file transfer protocol (FTP) credentials: This approach which lets attackers access and change files on a Web server, is less likely to be noticed by Web site administrators as files can be spread subtly across a site

- Malicious adverts: Adverts are often pulled up randomly on Web sites, with the site owners unable to control exactly what appears; if malicious, an advert will lead the victim to malware

- Attacks on backend Web site-hosting companies, using SQL injection or stolen FTP credentials

- Exploitation of vulnerabilities on Web servers or in Web site-hosting software

- Cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks, where Web browser vulnerabilities allow script code from a remote Web site to be executed.

Sometimes, legitimate Web sites are compromised on a one-off basis, with the attackers carefully probing several sites until they find one with potential to be compromised. In other cases, legitimate sites are compromised using large-scale, highly automated campaigns where thousands of sites are trawled.

The bad guys also often go to considerable lengths to present a constantly shifting target. They know that compromises, stepping-stone redirect domains and endpoint malicious domains will be discovered once users begin to get infected. So they move on to compromise more sites and set up new domains--rapidly and continuously.

Attackers also prey on the all-too-widespread--and, as we've seen, all-too-mistaken--belief that legitimate sites are definitely "safe to surf". They do this, for instance, by registering domains that look very similar but are not identical to legitimate sites--a technique known as "typo-squatting".

In doing so, they hope users won't notice that the URL they're following is not quite what it seems and in fact leads straight to an infected Web site.

Dangerous domains

Examining the Web domains hosting, or redirecting visitors to, malicious content can provide an excellent insight into how the bad guys operate.

For example, an analysis of the age of malicious domains (that is, the amount of time between the date when a domain was registered and when it was first detected as having malicious content) reinforces many of the key points noted above.

The figure below shows the age distribution of domains blocked by MessageLabs hosted services between February and June 2009:

Around 16 percent of blocked domains were registered less than three months before being blocked for the first time. The majority of these domains were set up expressly to serve malware to visitors; the rest were new, legitimate domains equipped with inadequate security and so very quickly compromised.

The remaining 84 percent had registration dates of more than a few months, and perhaps even many years old. They're highly likely to be legitimate Web sites whose owners were unaware--for days, weeks or months--their site contained, or redirected to, malicious content. Even the Web sites of large, well-known businesses and organizations can become infected, so even the most sensible surfer is now in danger.

Each day, MessageLabs makes around 2,000 blocks of sites that host or redirect to malicious content, across around 240 domains. Almost half of the domains blocked are being blocked for the first time. This indicates that more and more legitimate sites are being compromised and new malicious sites are continually being established.

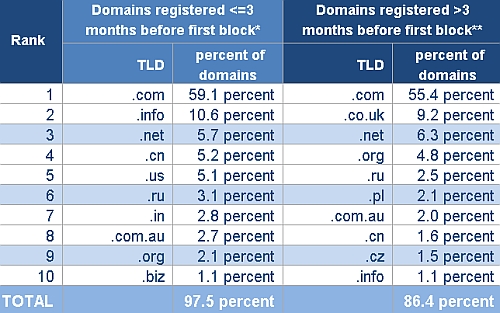

The figure below shows the most-used top-level domains (TLDs) identified by MessageLabs as hosting or redirecting to malicious content between February and June 2009:

* Mostly Web sites set up with malicious intent

** Mostly legitimate Web sites that have been compromised

The bad guys' predilection for .com is encouraged, no doubt, by its air of legitimacy--making it less likely to provoke suspicion. An additional point is June 2009 saw a rapid increase in blocks made on newly registered .cn domains, although these domains are not always hosted in China.

MessageLabs observations for the period February to June 2009, revealed that the United States hosts over 50 percent of the legitimate domains that were compromised--domains which are attracting an awful lot of victims. By contrast, the younger domains are much more widely scattered, with some noteworthy concentrations in Eastern Europe, Canada and the Far East.

Most interesting is China, hosting 10 percent of these younger domains and responsible for a massive 44 percent of blocks. Just two Internet Protocol (IP) addresses are under one registrar account for most of the blocks, with the main threat in the last few months being a Trojan hidden in a dummy "help" page.

It should be remembered, though, that the location of cybercriminals setting up a malicious Web site doesn't necessarily have to match the country where the domain is hosted.

For any business, the Internet represents a potential minefield. Nothing can be assumed to be "safe". Without effective protection in place, any organization could find its operations fundamentally--and perhaps even critically--compromised. Indeed, it could unknowingly find its machines not just becoming infected but also playing a role in espionage, extortion and other serious criminal activities.

Bjorn Engelhardt is Symantec's Asia-Pacific head of MessageLabs and SaaS group for Asia-Pacific and Japan.