On publishing, paywalls and the information fabric of the Web

Google said Tuesday that it will let publishers set a daily limit on the number of articles readers can view for free through its popular search engine.

The change, explained at length in a post on the Google News blog, will let publishers limit readers to five free articles per day.

The reason for this change: content providers, under fire from dropping advertising revenue, are angry that their content spreads around the web for users' enjoyment -- and potentially aggregation sites' benefit, if those sites run ads against that content -- without increasing their own coffers.

In other words: is it preferable to be popular, or wealthy?

The content in question is virtually everything that you read on the Web, from the photos and commentary to the very news itself. (Can you own a news story? Some organizations would like to think so.)

Google's emergence in the 1990s as the great(est) unifying Web portal meant that suddenly, a publication's content reached far wider than it previously did. As a user, you may have also read it from a broadcast organization such as FOX, or a highly-ranked aggregation site such as the Huffington Post.

But you very well may have read about the 2007 school shooting in Greenville, Texas from the Rockwall County Herald Banner, the local community newspaper closest to the event and the top-ranked source for the story on Google.

The publications most angered about this are those that do the most original reporting, such as the Wall Street Journal, always among the top three newspapers in the nation with the highest circulation. The CEO of the parent company of that paper, News Corp.'s Rupert Murdoch, recently threatened to block Google from displaying the Journal's articles in its results.

(The Journal already charges subscription fees for access to some of its online content.)

Google's "first click free" program aims to calm some of those concerns. It allows you, the Google News or Search user, to find and read articles -- even if they are behind a subscription paywall.

Here's the catch: Your first click to the content is free, but when you click on additional links on the site, the publisher can show a payment or registration request.

Google has now updated the program so that publishers can limit you, the reader, to no more than five pages per day -- no registration or subscription necessary.

The idea behind it: the wall will stop frequent visits to the site without payment or registration, while still allowing visibility.

For Google, that means staying on top.

For publishers, that means staying visible while monetizing a reader's eyeballs.

The solution is a tricky one, however, because popularity and revenue do not necessarily have anything to do with each other.

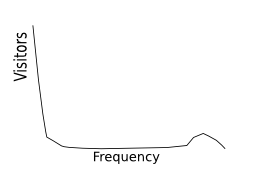

Take a look at this diagram from new media strategist Steve Yelvington, from his recent post, "Thinking about a paywall? Read this first":

What you're looking at is a usage graph -- return visits, or pages per unique user per month. On the left side is your publication's popularity -- reach among readers -- which is far and wide. This is where search engine optimization comes in -- the better optimized your site, the more eyeballs it can reach, right?

But these people are less valuable to advertisers. Some may fit your target market, but many are just fly-bys.

But as you move right on the graph -- more visits per user -- the line on the graph drops. After one or two visits -- likely referred from a search engine or aggregation site -- your actual readership drops, big time. The readers on the left don't care about the publication; they care about the specific news story. Who it comes from doesn't really matter, so long as it's accurate and comprehensive.

But see that little bump on the right side? Those are regular readers -- the folks you recognize in the comments section, the folks that are engaged. Those folks don't read one story -- they read many. They're not coming for the specific content -- they're coming to read your publication, whatever it publishes.

These people are very valuable to advertisers.

The point of a paywall is to force people to pay for your content (hopefully, they already want to). The problem is that the many readers on the left side of the graph won't pay. Many of the ones on the right will, but they're not nearly as many as who's on the left.

What's more, a paywall is a great way to disinterest any potential joiners on the left. It's a bit like circling the wagons -- it protects what you've got, but doesn't let any more in.

But more people access sites using Google than directly. Block your site's No. 1 user, Google, and you block your own visibility.

Google's approach is to say, "We'll let you through the first door, and if you like what you see, you can pay to go deeper." They're taking more steps to become the gatekeeper to the show; they won't be levying a cover charge at the door (let them do that inside!) but they'll happy erect a velvet rope based on daily frequency.

In other words: Google is taking the burden of access on itself.

The question is whether publishers will take advantage of it, and whether it will be to their benefit or detriment. Niche publications can get away with charging because they're not heavily reliant on drive-bys. Broad publications or aggregation sites, on the other hand, could have more of a problem.

That means that publishers will soon have to make a judgment call on how much of a traffic hit they're willing to take versus how much of a revenue increase they'll see.

Will it move the needle enough? I'm not so sure. For sure, Google's strategy removes the "circled wagons" concept I detailed above. And it certainly makes it easier, technically speaking, for publishers to levy subscription charges.

But it seems to me like Google is (rightfully) passing the buck back to publishers: we'll make it technically easier for you to put up a paywall, but we won't decide whether to implement one for your publication. (So long as you don't disrupt the balance of the searchable Web!)

Or to return to Yelvington's diagram: we'll let you folks on the left do your thing, but we'll make sure you folks on the right are paying for your loyalism. And if you are an interested enough leftie to move to the right, pay up, fella.

If publishers jump on paywalls, what that means for you -- the reader, consumer of information on the Internet -- is that you may start paying for access to your favorite sites.

But one visit to the Banner Herald? No problem.

The question that remains for publishers: do users consume enough news to make the whole thing worthwhile? (My guess: No.)

Google is keeping Internet visibility intact without making the call on a paywall.

Will you pay?