Photoshop CC pirated already? You're missing the point

I can't say I was surprised to read the giddy headline "Adobe Photoshop CC Has Already Been Pirated In Just One Day" this morning. If we've learned nothing about humanity through the lens of technology, it's this: "If there's a will, there's a way."

When Adobe first decided to move its entire Creative Suite software suite to the cloud, the haters were the first to complain. Our sister site CNET conducted a survey about the sentiment around this move, and participants were defiant: 76 percent said they'd resist the move to the cloud. (This explains a lot about Microsoft's cockroach-like Windows XP operating system, by the way.)

Lifehacker's Adam Dachis was rather bitter about the decision: "We hope to see them at least treat their customers with a little more respect and remove the year-long requirement without an adding cost," he wrote. Less journalistic folk were simply apopleptic.

"TERRIBLE IDEA!" one design director said.

"SUPREMELY terrible," tech pundits UpgradeOrDie added. (No, the irony isn't lost on me, either.)

"Most Adobe updates add bloat. Now, I *must* pay? Fuck that," web designer Jeff White said in a huff.

Fun, right? You could say this decision went over about as well as when U.S. wireless carriers implemented tiered payment plans. (With that, customers screamed about the loss of unlimited service, even though a majority of them did not use it. It is a nation founded on freedom, I'll give you that.)

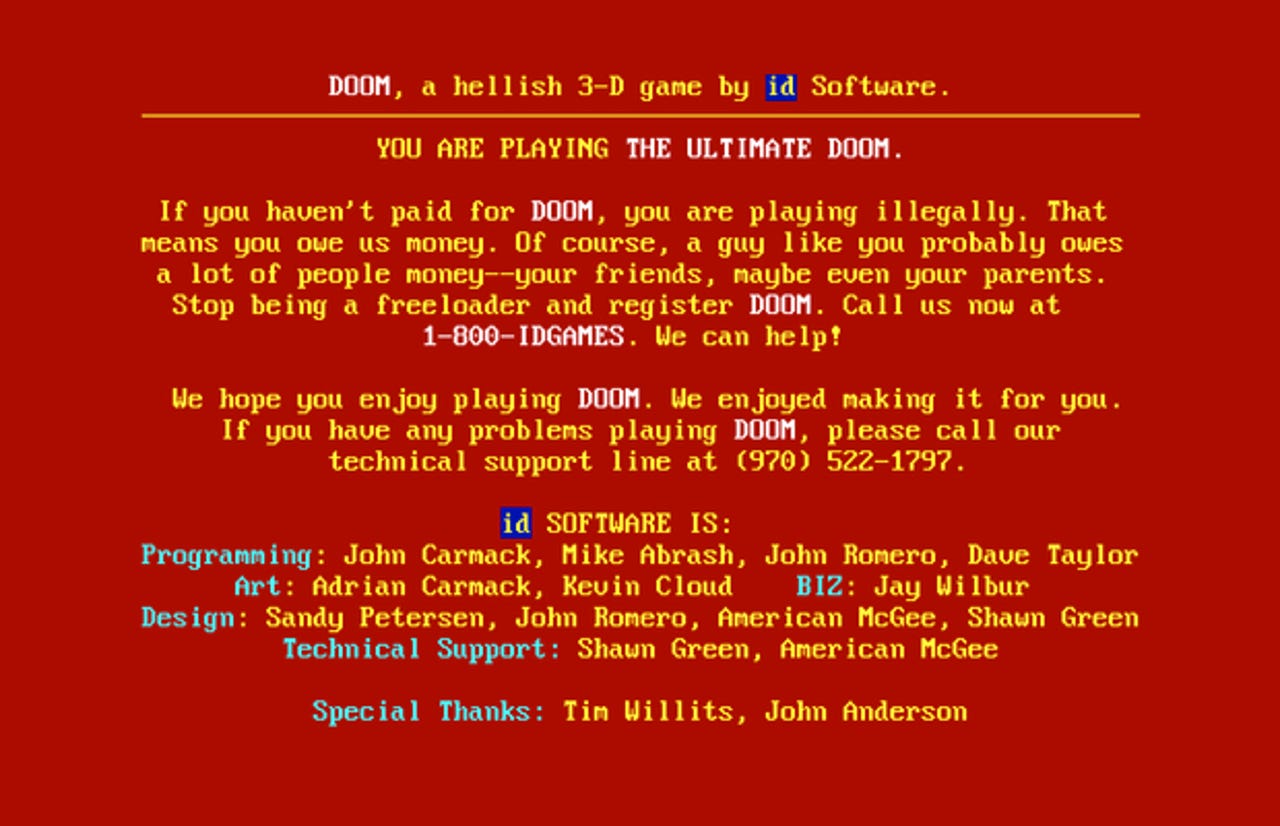

The main criticism of Adobe's move to cloud-based software distribution (but not software-as-a-service, to be clear!) is that the company wants to crack down on piracy.

Photofocus' Scott Bourne touched on exactly this in one of the first coherent op-eds published in the wake of the news: "The haters are mad because they realize they can no longer pirate copies of Photoshop," he wrote with striking clarity, adding: "This is the REAL reason for 90 percent of the noise." (Officially, Adobe denies this.)

The truth is that Adobe's move to cloud-based distribution does effectively crack down on some piracy, but not from a technological perspective, rather, an economic one. (The proverbial carrot, instead of the proverbial stick.) With today's desktop-based Suite, you need to spend $700 to use the full version of Photoshop. In Creative Cloud, you can start using it for $20 per month, or $240 per year. The bar for entry is much lower.

In other words, Adobe isn't going to stop the hardcore hacker from pirating its software, even if the company distributes the product from its own servers. But it may provide enough economic incentive for regular people to just pay up.

(As a brief aside: Have you ever stopped to think how strange it is that "Photoshop" has crept into linguistic usage as a word to describe the manipulation of images? In one sense, sure: Adobe dominates the market. In another sense, this is crazy, because the vast majority of regular people who use this term have never used this quite expensive piece of professional software. That's multiples of the price Microsoft levies for its Office suite, and about the average price consumers pay for an entire laptop computer. So you start to wonder: just how many people have come into contact with a pirated version of Photoshop, exactly?)

We can look to Apple and iTunes in this regard: one part of the reason that company made so much inroads in the purchase of media is that it made it seamless; a second part is that it made it cheaper. Instead of $15 for a likely indulgent Kanye West album, I can buy a few songs for $1 each. Instead of a $30 DVD for season one of the U.S. television series Mad Men, I can buy the one or two episodes I missed for $3 each. This vibrant ecosystem has mostly curbed the casual piracy practiced by normal people in the heady days of Napster and its ilk, at the turn of the millennium.

Does a product cost more à la carte? Sure. But this is comparing apples to oranges; there is value in the smaller unit's convenience and accessibility. Sure, some people prefer warehouse-style purchases that emphasize quantity. But for another set, it's the lack of it that is most valuable. Some people will happily pay more for less product. Not everyone wants a gallon of mustard.

(Ever tell a cashier "Keep the change?" because you didn't want to deal with it? At that moment, you are making a decision to pay more for less product. In this case, currency itself.)

By lowering the entry price of its software suite and the unit of value that corresponds to it, Adobe has made its flagship software more accessible to more people in an age when digital media manipulation is more democratic than ever. It's a smart move that expands its potential customer base. It also may be enough to push piracy back to the fringe.