Running your SOA like a Web startup

One of the more striking differences between IT and the online world these days is the contrast between traditional enterprise service-oriented architecture and its equivalent on the Web, open APIs. More and more lessons are coming from the online space, providing key insights into how we might invigorate the way we open up our IT systems for maximum value.

SOA does not have the same business urgency and lacks critical focus in this regard in most organizations. So while some new data shows that 75% of all large enterprises will be using SOA by the end of this year (and 60% will even be expanding it), the most obvious successes with service-oriented approaches aren't classical organizations at all. They are Web companies that offer APIs out of a basic need: To build a network of partnerships quickly and cheaply as well as tap into external innovation and inexpensive 3rd party investment.

A quick examination of Google News shows several useful new public-facing Web services (aka open APIs) that were announced this week, including one for Microsoft's Bing as well as from smaller companies like School Loop, which just launched an API that "lets gradebook and assessment systems pull data--such as rosters and assignments--from School Loop and write scores into the School Loop gradebook for display to parents, teachers, students, and other stakeholders." Both of these APIs let anyone, anywhere build applications that interact with and incorporate their respective capabilities.

These are just two typical examples of more than 40 new APIs that were released to the world over the last 30 days alone, according to Programmable Web's API dashboard, currently the most reliable source for such information. This pace of release is fairly steady: A "global SOA" is growing up around us on the Web.

Joe McKendrick recently asked here on ZDNet if we needed an iTunes model for Web services. The reality is, it already exists -- albeit in Web-friendly, simple form -- and not in the failed visions of UDDI directories of yore, but in the pragmatic release of hundreds and hundreds of new APIs every year.

SOA and Open APIs: Close Cousins

Now, it's also true that SOA initiatives in large companies generally don't publicly announce their internal developments, so it's much harder to get a sense of what is being created and used in most organizations. However it's fairly clear that there are some significant differences and outcomes between these two approaches for open services, even as they ostensibly have the same goals on the face of it: To encourage interoperability between different business systems and enable opportunities that would otherwise be too difficult, expensive, or time-consuming to capture.

What's especially intriguing about these two sides of the same coin are the innate assumptions that they make: SOA is usually an overhead effort (thought it can also be done on the ground) between IT and the business which ultimately allows businesses to achieve improved results and even serendipitous outcomes when it comes to the integration and leverage of existing investments in systems and data. The ROI is very often hard to measure and rapid improvements to the business are usually not the norm. SOAs also tend to be more inward facing and designed for internal consumption.

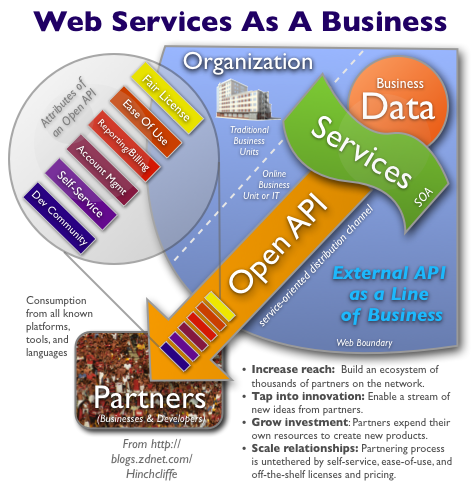

Contrast this with open APIs, in which the API is considered of primary strategic advantage to the business. The view is the investment in the development of an API is warranted because of immediate benefits that can be gained: increased reach to new customers on the network, tapping into external innovation, increased 3rd party investment, and a scalable model for 3rd party relationships. Interestingly, the bigger the organization, the more value an API has to offers to existing and potential partners, primarily because of the data tends to be richer and more valuable and/or the functionality it exposes is world-class through the success of the enclosing business. This is a vision where a service-oriented business channel (open APIs, not Web pages) often becomes the dominant channel for interaction with their customers as it arguably has for market leaders such as Amazon, Twitter, and others. Unlike most SOA efforts, APIs also tend to be designed for consumption by the broader world, though they are certainly used internally as well.

In would be a gross oversimplification to say that SOA is a technical approach to solving a outstanding set of business problems and open APIs are a business solution that uses a technical approach, but increasingly that seems to be the case. A couple of years ago I asked if it was the timing was right for businesses to open up to the cloud particularly since a near majority of CIOs were clamoring for it. For more enterprises, that just hasn't happened, leaving strategic gaps in execution that has helped lead to the recent discussions about the possibility of the quiet death of SOA.

These points highlight a key difference between the goals and strategies of SOA and open APIs. Open APIs are about business, first and foremost, by attracting developers to build useful new things that are mutually beneficial. In creating a highly consumable and valuable set of services, Web companies hope to attract over time the cumulative efforts of an ecosystem of developers and their respective businesses. It's the classic "turning an application into a platform" strategy that has been successful for top Web 2.0 companies: SOA does the same thing with a different focus, which I've discussed here on this blog for several years now. The success of the API model is clear: Back only a year ago there were only 700 APIs in the global SOA. Today there are almost double that, nearing 1400. Collectively, they provide a backbone of services in which almost any kind of service can be found and which companies can use to create the richest and most competitive products and services for their customers.

Open businesses that create value: Two perspectives

So in the end, if all this openness, partnership, and interoperability on the network is so good for us, where are we falling short in terms of building service-oriented businesses? This question is particularly germane to the enterprise where SOA has frequently been perceived as providing lackluster results recently. To get a sense of the issues, I asked two well-known figures in their respective fields to give us some additional perspective.

First off, I contacted Burton Group's Anne Manes, a respected authority on enterprise SOA, a central figure in the debates on the future of SOA, and in my opinion a level-headed voice of reason about technology and business, asking her to briefly summarize what it takes to make SOA successful for a business. She provided this reply:

IT organizations must realize that SOA is not an end goal. SOA is a means to an end: delivering systems that are more manageable, flexible, and agile. But the primary goal must be to support the ever-changing needs of the business. IT groups should spend less time focusing on technology and infrastructure, and instead focus on delivering systems (aka services) that deliver measurable business value.

I then went to Oren Michels, CEO of Mashery.com, a leading firm that helps large companies like Netflix, MTV, Best Buy, and the World Bank deliver open APIs to their internal and external customers, and asked him the same thing. Here's what he said:

Providers of Web services benefit from the creation of a distribution channel for their core services. Few companies have as their core competency the creation and running of a distribution channel, and rarely can a company grow their channel nearly as quickly as they like. Taking advantage of the reach of the partners who incorporate your Web services allows you to focus on making those services better - in other words, focusing on what differentiates you.

So whether you are a provider or consumer of Web services, it comes down to focus - you build, run and manage the things that define and differentiate you and make those Web services powerful, reliable, scalable, secure, and bulletproof. Providing that value will get you paid. Building and running things that are available elsewhere will cause you to lose focus, which is a direct path to failure.

Both of these views underscore the same basic point: Business value is the driver for the success of services in an organization, period. Both Anne and Oren also independently used the word 'focus' as a key discriminator for the success of a service-oriented channel (either SOA or open API.) Oren's view was even more extreme however; in an online world where lack of engagement doesn't just mean a failed services endeavor, it often means the end of your business, survival is increasingly hinged upon being able to provide an attractive set of services for your most important customers; your business partners.

It's very telling that Twitter still gets 10 times more usage through its API from partners than through its Web interface and this ratio is not unusual. It's also very uncommon for a new Web product to launch without an API; services are the route to success in today's Web where if you have anything of value, you need to make sure it has leverage. SOA does not have the same business urgency and lacks critical focus in this regard in most organizations.

In short, traditional enterprise SOA has a lot to learn from the open API world. Not all results are spectacular, but there are plenty of excellent examples and it's part of an increasingly urgent call for open business models and without a capable and healthy services ecosystem that functions well on the open network, organizations are increasingly at a disadvantage in a Web-oriented world.

How can SOA's take the lessons of open APIs and apply them, fortunately, the means are straightforward and are slightly more business-oriented than they are technical. Finally, some SOAs are indeed doing these things, but too many are missing the opportunities that face them.

How to run your SOA like a Web startup

- Ease of Use. Making services consumable from any platform, tool, or programming language is vital for the adoption of an API when customers will be using whatever local tools they have at their disposal. Traditional SOAs often use more complex, less Web-friendly technologies that make it hard to interoperate unless trading partners are using a very similar set of tools. On the Web, using extremely simple, high performance models like REST or WOA are common and are easily used to create mashups. Many APIs provide reference implementations, testing tools, and even Web widgets that are ready to deploy with a cut-and-paste (Google Maps for example) to make sure they have an edge. Plenty of documentation and support is provided as well.

- Reporting/Billing. Making sure customers understand what it costs, are encouraged to consume resources wisely, and can measure and see what they're using ensures a wise and appropriate use of services with a positive feedback loop. It also frequently provides the business model for an API, though many are just happy to get the traffic, investment, or innovation. In SOA, this could be a chargeback model of some kind internally (vital for making consumption manageable and responsible) but for trading partners, might indeed be an outright bill or other compensation.

- Account Management. Open APIs are all strongly keyed to who is using them and is used for providing customer service, tracking usage, and creating accountability. It also is essential for quality of service levels for difference classes of customers and other more sophisticated measures. In addition to identifying all requests (and securing the API), accounts also allows badly behaving partners to be identified and curtailed. An account model for customers is a first-class citizen in an API.

- Self-Service. One of the key aspects of public APIs is that they can be used without a lengthy company-to-company negotiation and partnership process. This is more important than it seems since it makes it possible to acquire far more partners more quickly and cost-effectively than otherwise possible. Sign-up, licensing, integration, and testing, and payments are all automated and online for most APIs, making it possible for a single company to deal with hundreds or even in some cases (like Salesforce, Amazon, Google, and others) hundreds of thousands of API customers in a cost-effective manner. Self-service APIs make it possible for very lightweight integration where the partner does virtually all the work to integrate with your system; an API provider just needs to create a well-documented, scalable API, built and paid for once, instead of engaging in many 3rd party integration efforts.

- Developer Community. APIs depend upon providing an eminently attractive and usable option for developers to adopt. If initial proof-of-concepts work out, an API then becomes a business relationship. It's for this reason that most APIs take great pains to entice and keep developers, which will often make the long-term decision on if a set of services is viable to use, consequently an API that does not take good care of its developers must have best-of-breed or sole-source data or capability. Today on the Web it's standard to have a full-blown developer community with support staff, forums, issue tracking, and all the trappings of a developer product. Without providing developers with the tools and information they need to succeed, it's hard for a business to build and rely upon another's services, especially when questions and issues aren't resolved. This underscores the customer-centric nature of open APIs and SOA has the exact same requirements, though there is usually less formality in developer support. Note that larger API providers even have full-time marketing/evangelism staff that encourage developers to be learn about and consume their service offerings instead of re-inventing the wheel and building it themselves. For SOAs, this would be outreach to internal business units as well as 3rd party partners.

- Fair license. Unless an API provider provides some permission to use the functionality and data in another business, there's little incentive for others to contribute their resources and innovation to create new products incorporating that API. An ideal license is one that gives permission for the consumers of API services to re-use its capabilities in running their business will provide the legal ability to use the API in as flexible a manner as possible. The same with SOA; I've seen more than one SOA where internal business units didn't like the use of their data elsewhere in the organization and put a stop to it. This will kill the business value of services and it's the wrong focus.

There are other important aspects of open APIs such as governance (rate limiting, security audits, version management) and service-level agreements, but these are more readily understood by today's enterprises. But for those that are seeking to make their services more critical to the business, even vital to the bottom line (see the great revenue graph from Amazon), the points above enumerate many of the differences between services that drive value and services that don't.

The emergent business environment of the Web has provided hard lessons for online companies that must survive in the rough and tumble world of the Internet, through any techniques possible. Along the way, this increasingly seems to have proven out a model for services that contains many hard-nosed lessons for SOA, namely: 1) Our business vision and partner outreach for SOA needs significant improvement and, 2) opening up to the cloud will be a key next step for many businesses looking for the full value from their investments. These lessons are continuing to come in and we'll look at some stories, including cloud computing/SOA, the new Semantic Web, and others in an upcoming post soon.

How are you reaping business value from your SOA? Please add comments in Talkback below and I'll do my best to respond to every comment.