IBM at 100: 15 inflection points in history

The company known as International Business Machines turns 100 years old today, and it's been one hell of a ride.

In the dynamic American economy, not many companies make it this long -- much less remain this successful. You can probably count them on one hand: Ford. GE. Several banks, which have merged and acquired themselves right out of recognition.

All of these companies' stories share the same theme: adaptability. Facing bankruptcy, Ford spent its way out of the latest recession. GE moved beyond lighting into infrastructure. And, as we'll learn below, IBM let data guide it to success.

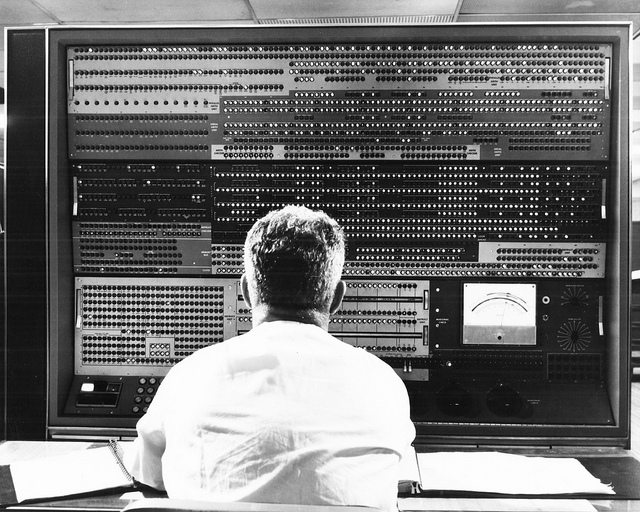

[Photo Gallery: IBM's 100 years of THINKing big]

All companies experience the highest highs and (almost) the lowest lows. A company as old as IBM has experienced far more than most -- and lived to tell the tale.

Below, 15 moments in IBM's storied history that helped make it the company it is today:

1914: Creating a corporate mission. IBM president and visionary Thomas Watson focuses the attention of the Computing Tabulating Recording Corporation -- IBM's former name; it was changed in 1924 -- away from small office products and toward large-scale, custom-built tabulating solutions for businesses. Amazingly, it retains this focus today.

1928: Fostering a culture of innovation. The "Suggestion Plan" program -- which gave cash rewards to employees who contributed viable ideas on how to improve IBM products and procedures -- makes its debut. It's the beginning of the company's nearly unbroken investment in research and development.

1943: Moving toward talent. IBM establishes a presence in San Jose, Calif. to take advantage of a growing hive of electronics research in what would much later be called "Silicon Valley." Four years later, this facility would invent the hard disk drive.

1953: Reorganizing for growth. Taking the baton from his father, Thomas Watson Jr. dramatically restructures IBM in a fashion that represents modern management structure today, allowing him better visibility into the company. He transitions the company from medium-sized maker of tabulating equipment and typewriters to the world's leading computer company, codifying its values and boosting R&D spending to 9 percent. He also continued the SAGE computerized tracking system for the U.S. Air Force, which brought in little profit but trained thousands of IBM workers in electronics.

1954: Tapping the Ivory Tower. IBM begins working with academia to get closer to cutting edge research. The company's work in real-time computing with MIT in 1952 helped land it a contract to develop the SAGE computer for the U.S. Air Force; it built 56 for $30 million each. IBM also decided at this time to cede computer programming to the RAND Corporation, which it believed would soon be obsolete.

1957: Betting the farm -- and winning. IBM turns away from tubes and goes whole hog into solid-state electronics. From a Watson, Jr. product development policy statement: "It shall be the policy of IBM to use solid-state circuitry in all machine developments. Furthermore, no new commercial machines or devices shall be announced which make primary use of tube circuitry."

1964: Turning its back on success. IBM introduces System/360, the first major family of computers to use interchangeable software and peripheral equipment. Fortune magazine called the move "I.B.M.'s $5,000,000,000 Gamble" because compatibility wasn't a guaranteed business advantage; success for the product would cannibalize IBM's existing, revenue-producing computer product lines. In two years it became the dominant mainframe computer and has been the foundation for the company's mainframe work ever since.

1969: Finding value in software, by force. IBM vs. U.S. is filed, beginning a 13-year slog into antitrust litigation over IBM's digital computer dominance. The suit is eventually dismissed in 1982, but it provokes the company to unbundle software and services from hardware sales, giving monetary value to what had previously been free -- software -- and setting the stage for the company's business approach today.

1981: Turning toward the consumer for the quick fix. IBM uses its business prestige to move into consumer realm with the IBM PC. Many businesses purchased them -- they were $1,565 each -- with purchases not by corporate computer departments, as the PC was not seen as a "proper" computer, but by middle managers and senior staff seeking to solve problems. (This phenomenon foreshadows at today's battle between IT departments and bring-your-own-device mobile policies.) While it fueled the success of this product line, it also fractured IBM's business model of offering integrated solutions, and eroded its future revenues since it no longer had long-standing relationships with decision-makers.

1988: Forgetting the lessons of '64. IBM partners with the University of Michigan and MCI Communications to create the National Science Foundation Network (NSFNet), a step toward the creation of the Internet. But within five years, the company backed away from Internet protocols and router technologies in order to support its existing cash cows, missing the 1990s boom market.

1991: Reorganizing away from its mission. The company posts its first operating loss and CEO John Akers sells off non-core businesses (typewriters, Lexmark printers, etc.). More importantly, Akers begins to reorganize the company into more autonomous business units to compete directly with the likes of Microsoft, Oracle, Novell, HP and Seagate, all tech companies with specific niches.

1993: Channeling '53 and '14 in the face of collapse. After two consecutive years of reporting losses in excess of $1 billion, IBM announces an $8.10 billion loss for the 1992 financial year, then the largest single-year corporate loss in U.S. history. New CEO Louis Gerstner decides to not break the company up, but keep it intact and slim it down, consolidating it around integrated solutions. A new business model appears: shed commodity businesses and focus on high-margin opportunities. Out went low-margin businesses -- mostly hardware -- and in came global services. IBM become brand agnostic, integrating whatever technologies the client requested.

1995: Rediscovering a mission. IBM makes a bet on software, acquiring Lotus. It leaves consumer applications to other companies and instead focuses on middleware (with corresponding higher margins).

2005: Selling toward a rediscovered mission. IBM turns its back on the consumer market and sells its computer product lines, including the ThinkPad (first introduced in 1992), to China's Lenovo.

2008: Acquiring toward a rediscovered mission. IBM acquires Telelogic and Cognos, reprioritizing software and data intelligence -- in other words, middleware -- as core businesses. The deals end a string of more than 50 software acquisitions in eight years that include Princeton Softech, DataMirror, SRD, Trigo, Alphablox and PWC's consulting business.

The lesson here? History repeats itself. IBM's focus on innovation has indeed helped it adapt -- proactively, I might add -- to a changing market. When it began to rest on its laurels, play the short-term game and ignore its central tenet to offer "global business solutions" -- whatever the phrase meant at the time -- IBM began to descend into failure.

More from our colleague Michelle Miller at CBS News:

Related: