Blade PCs: the ultimate managed desktops

Although many organisations are satisfied with conventional desktop PCs, some want to manage their systems so tightly that they have replaced their desktop computers with thin clients connected to back-office servers that provide the computing and storage resources. These servers usually deliver a full Windows desktop and applications to users via a network connection. Users connect via a protocol such as Microsoft RDP (Remote Desktop Protocol) or Citrix ICA (Independent Computing Architecture), so this approach also works well for remote workers. However, the server environment is fairly complex and requires careful management by skilled IT staff. Also, some applications work better in this model than others. For example, one user running a processor-intensive application would probably affect all the other users of the application server. There’s also a risk that a single user could bring down the entire application server by running a program that has a bug or turns out to be infected with a virus.

By contrast, blade-based desktop PCs offer many of the advantages and few of the disadvantages of traditional thin-client systems. With the promise of predictable performance, excellent support for remote workers, lower costs of ownership plus better security, reliability and manageability, blade PCs are rapidly gaining ground in businesses.

Most IT staff would also agree that desktop PCs are a headache when it comes to security. For example, removable media drives and other USB storage devices could be used to steal information or to introduce a virus or other malware into the network. Some organisations also have particularly stringent security procedures to protect data on desktop systems. For instance, some companies use desktop PCs with removable hard drives and insist that users remove and lock away the hard disks when they leave their desks. USB sticks and removable hard drives can be tricky to manage using traditional desktop PCs, but blade PCs are normally located in a secure datacentre, thus preventing physical access to the disk drives and USB ports.

Blade PC architectures

ClearCube was the first vendor to offer blade PCs, and it remains the only one to concentrate purely on desktop hardware. ClearCube's solution is built around a rack-mounted blade chassis There are two chassis types: the 3U R4300, which houses eight R-series blades, and the 6U A3000, which houses ten A-series blades — each blade being essentially a powerful PC. The rack itself is normally housed out of harm’s way in a datacentre: a standard six-foot rack can accommodate fourteen R-series chassis for a total of 112 blades or seven A-series chassis for a total of 70 blades.

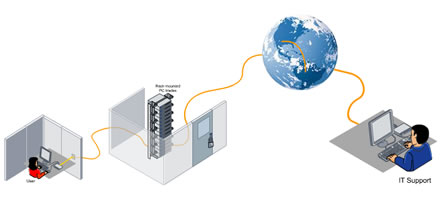

Obviously users need a monitor, mouse and keyboard on their desk, but rather than connecting these to a thin client or desktop PC, ClearCube uses a video-cassette-sized cable connection unit, called a 'user port'. The company sells two types of port, both of which provide connections for local printers and peripherals that can be tightly controlled by management software to prevent unauthorised use. C/Port devices use analogue electronics to minimise delays and connect to the blade with up to 200m of standard Cat 5 cabling. By contrast, I/Port devices use a digital interface and standard TCP/IP signalling, so they can be connected with standard LAN and WAN links over unlimited distances. Companies could use I/Ports to build a disaster recovery system for their desktop users, for example, by putting the racks of ClearCube blades in a secure hosting facility and connecting their desktop users via I/Ports and internet links.

Last year HP began offering blade desktops along similar lines to ClearCube's products. HP’s Blade Workstation is based on its C-Class blades. For normal desktop users HP also offers lower-specification blades based on its bc2500 Blade PC. HP does not offer a simple ‘port’-type option to minimise complexity on the desktop, so HP blade PCs must be used with thin clients or ordinary desktop PCs. HP reckons a typical Blade Workstation deployment would cost about $4,000 (~£2,000) per desktop, while Blade PCs come in at about $1,200 (~£600) per user.

IBM is a major presence in the blade market with its BladeCenter servers. The company also launched its Workstation Blade in May, and for a year or so has been offering blade servers configured with Citrix Presentation Server or VMware virtualisation tools to deliver managed desktops to users equipped with thin-client terminals.

ClearCube: a client-only solution

ClearCube has been selling its blades for about seven years. Unlike HP and IBM, which concentrate mainly on blade server hardware, ClearCube is focused purely on providing blade solutions for desktop users.

Paul Dunford, director of channel sales for the EMEA region, says that ClearCube's approach sprang from an understanding of the problems associated with using conventional desktop systems. PCs are not very manageable or very secure, says Dunford, and many firms would like to reduce the costs and delays associated with sending IT staff to fix a malfunctioning PC located on someone’s desk. In many cases, it takes longer to get an engineer in front of a broken PC than it does for the engineer to fix the problem.

These problems can be bad enough for relatively small firms operating in a single building, but multi-site operations and challenging locations can prove a real headache. For example, sending an engineer off-site to fix a PC in a remote office is likely to be an expensive exercise. In many cases, the cost of downtime must also be considered: at a simple level, downtime means that people can't work as they would normally. But the cost of downtime escalates rapidly if the broken PC is, for example, located in an operating theatre or some other sterile area that can't be used until the PC has been fixed.

One of the key reasons for buying blade PCs is to minimise downtime. With blades, if the PC develops a hardware fault, a replacement can easily be switched into place — probably within a few minutes. Visits to users' desks should not be necessary.

The virtualisation effect

Although IBM offers blade PCs with virtualisation, HP does not currently recommend using virtualisation to host more than one desktop per blade. ClearCube, meanwhile, offers virtualisation as an option to reduce the cost per desktop.

Without virtualisation, each desktop user must be allocated one PC blade, which ClearCube reckons costs a typical customer about $4,000 (~£2,000) per user. However, virtualisation can be used to put up to 12 desktops on each blade. Even with the cost of the additional VMware ESX Server virtualisation software taken into account, ClearCube calculates that this brings the cost per seat down to about $1,200 (~$600). Of course, companies that are happy to use virtualisation could use fewer larger servers rather than many blades. However, virtualisation implies sharing processing power and memory between several users, and this only works well when most users are relatively inactive. With poorly configured virtualisation, a single user running CPU-intensive software could reduce the performance of other users' desktops. However, virtualisation tools such as ESX Server allow IT staff to apply 'reserves' and 'limits' on each user’s access to the CPU, so that each user gets guaranteed minimum and maximum levels of processing power.

Brokering

Although virtualisation reduces the cost per seat, it does raise the question of how users are allocated to blades. The simplest solution is for each user to be hardwired to a specific blade. However, this could make it tricky to switch users to a replacement blade in case of a fault. An alternative is to connect users to a broker, which then allocates virtual machines to users from its reserve.

The video problem

Virtualisation may be the way of the future, but it seems that video and other highly graphical applications could keep us hooked on hardware for a while yet. This is because streaming video and other graphically intensive applications don’t work well when the display is more than a few metres from the PC. IBM, HP and ClearCube all agree that Microsoft’s RDP is not suitable for these types of application.

ClearCube’s Dunford also says that some of the company's older I/Ports had similar problems because the digital circuitry introduced small delays. However, ClearCube recently launched the I9400 Series I/Port, which includes Teradici PCoIP hardware to improve performance to the level where PC blades and I/Ports can now be used for graphics-intensive applications. Indeed, the I9400 is powerful enough to support four simultaneous displays. For its part, HP uses a proprietary protocol to handle graphics and says it is powerful enough to support full-motion video on four screens. IBM also uses proprietary hardware to improve the performance of video and graphics on its blade systems.