PeaceTech Lab believes gear, gadgets, and know-how can sow peace amid conflict

Can technology drive positive change in conflict areas? The founders of PeaceTech Lab, an organization created by the U.S. Institute of Peace and spun off as a separate entity earlier this year, certainly think so. This weekend they're at Maker Faire in NYC celebrating the achievements of an Iraqi man who embodies that ethos.

"We work at the intersection of media, technology, and data collection," says Tim Receveur, director of the PeaceTech Exchanges program, which provides workshops organized by the PeaceTech Lab to empower peacebuilders. "We try to introduce low-cost, easy-to-implement technologies into conflict zones, and we do that by working closely with NGOs, journalists, and now government."

PeaceTech Exchanges have been held in areas rife with conflict, such as Iraq, Pakistan, Myanmar, and India. Workshop topics have included everything from preventing gender violence to increasing government transparency, and projects resulting from these workshops, which aim to train and empower locals, have been encouraging.

Some examples from Iraq include a crowd-sourced map that records instances of violence against journalists across the country, a plan to help communities map problems with infrastructure in order to increase government accountability, and an effort to streamline the national ID process. Each of these problems was identified by people in Iraq. PeaceTech Lab's job was to help tie them together in networks while providing the training, technology, and funding to make the solutions the locals came up with a reality.

"Technology is agnostic," says Derek Gildea, a specialist at PeaceTech Lab. "It can be used by anyone for any purpose. The trick is to help civil society be more effective in solving pressing problems. In Iraq, we're using technology to administer surveys and gather data. With the survey technology we introduced, people can go into refugee camps with smartphones or tablets and gather information about the outbreak of illness, for example, which the government may not know very much about."

In Turkey and Myanmar, where the free press is often restricted, one PeaceTech Exchanges intervention has been to provide journalists with tools to help them report more securely."Technology itself is not the solution," says Gildea, "but technology in the hands of people who build peace can make all the difference."

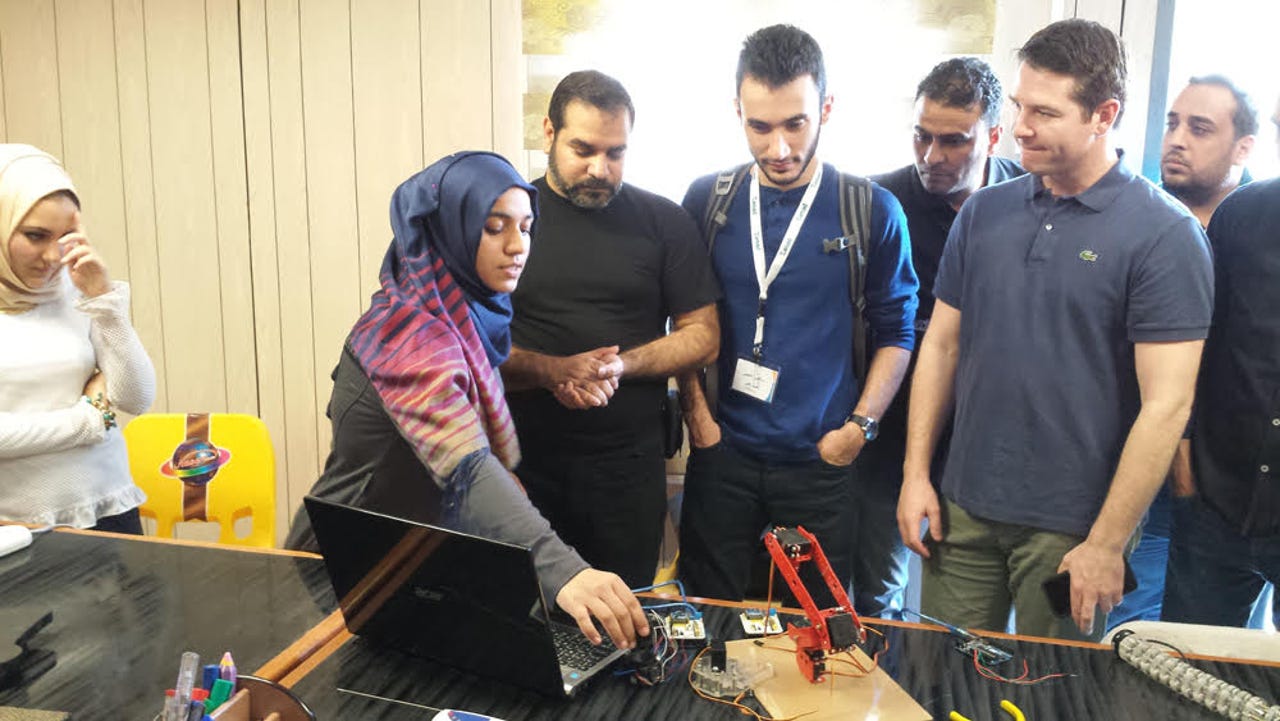

Nawres Arif, an Iraqi pharmacist-turned-tech trainer, is just such a person. He founded Science Camp in Basra, where he gives kids and university students hands-on tech training in 3D printing, engineering, app development, and robotics--tools not normally available in conflict zones, and certainly not in Basra.

"When we visited him for the first time," says Gildea, "we had to drive through rubble, through torn up streets, until we came to his house. He had set up two cargo containers, and inside he had tools that students could use to learn robotics, to perform basic maker activities, to do web design. There were about twenty young men and women there. What's really incredible is that women felt safe to do projects without a chaperon. This is conservative Iraq we're talking about."

Arif is able to run his program successfully in large part because he himself is an inventor and innovator working in a hostile environment. PeaceTech Lab recently combined efforts with MIT to secure necessary visas in order to bring him to the U.S. This weekend he'll be showcasing a motion capture suit he developed that allows for motion-capture animation in real-time. The technology may also prove useful as a human-machine interface platform and could be adapted to control highly dexterous robots.

Although Arif's visa application and travel has been supported by PeaceTech Lab, there is no formal relationship between the American organization and Arif or his Science Camp. "We just wanted to support an innovator who's helping a new generation figure out novel uses for technology in a conflict zone," says Receveur. "The reason we're interested in him is that we want to foster that tech environment in Basra. There's no more important place to build that up."