Evolve or die? How today's hardware giants are steering a course to irrelevancy

The mobile market is a tough place regardless of whether you're aiming squarely and consumers or business, and it's especially tough if you're aiming somewhere in between the two. However, if traditional hardware makers don't raise their game, they'll find themselves wrongfooted by competition from unexpected sources.

The division between hardware and software has historically tended to be a clear one. Take Microsoft or Google, for example: both are massive software companies that have traditionally shied away from going too far down the hardware route and, when they have, the results have been a mixed bag. Xbox, good. Kin, bad.

Consequently, a massive ecosystem of hardware makers has grown and flourished around the most successful software platforms, without those companies needing to deliver software (or subsequent updates) themselves. Consider a device maker like Dell or HP: all of them offer services and add-ons for the software that runs on their devices, but they're still better known for supplying the hardware side of the equation.

Some of technology's big names do manage to bestride both hardware and software alike and do so comfortably: Apple is the most notable company to sell both its own hardware and software, giving it supply chain benefits that only it and its biggest rivals, like Samsung, can enjoy. But for most of the other larger players, from Sony to Acer, the software they rely on to shift units is not their own.

And, with the cost of mobile hardware continuing to fall, smartphone and tablet makers are facing new threats from non-traditional sources with software companies and other brands alike muscling in on their turf.

Alarm bells?

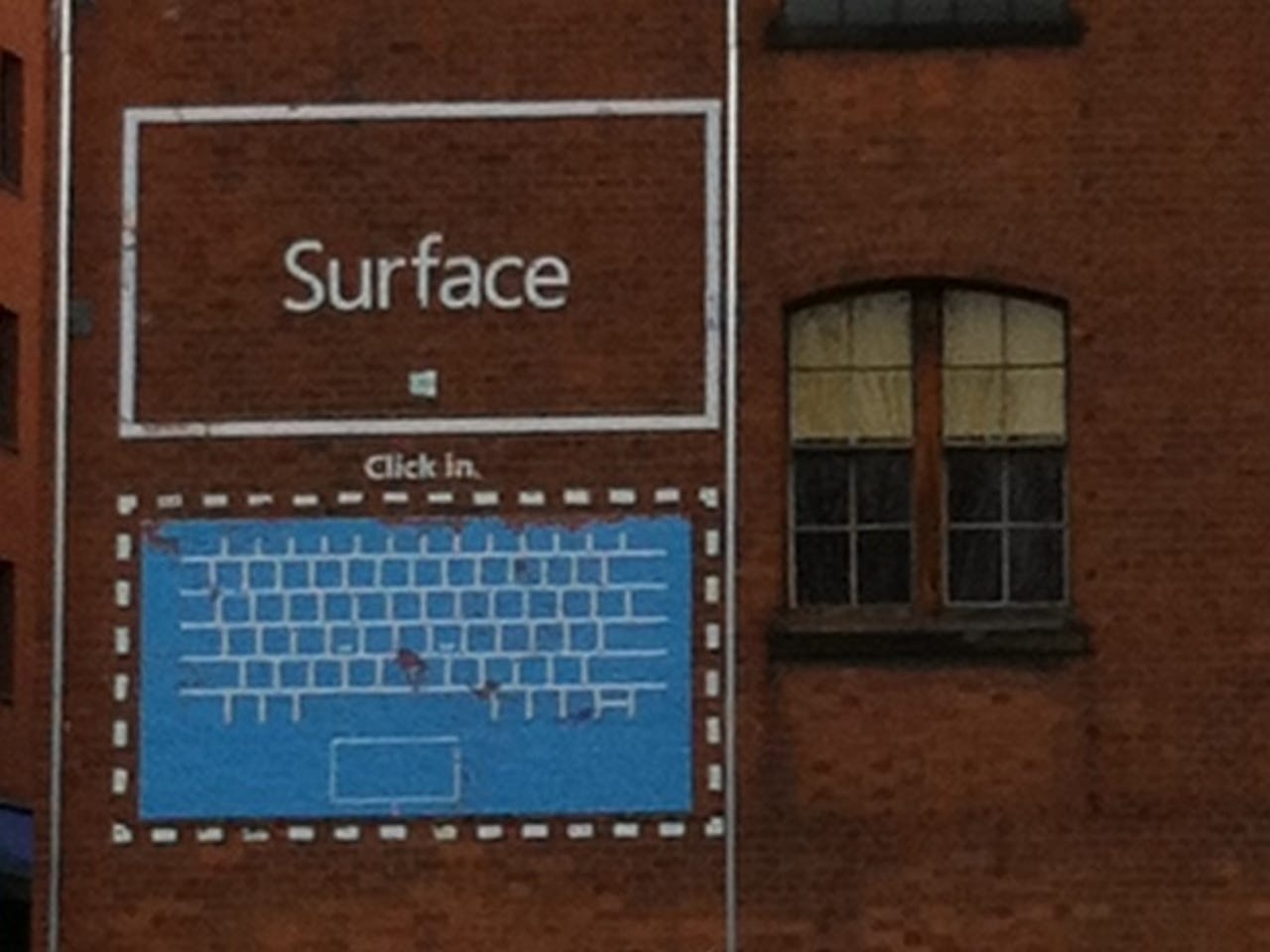

Take Microsoft's recent move into selling tablets with the Microsoft's Surface and Surface RT.

When the Surface tablets were first announced, some Windows OEMs recognised Microsoft was simply trying to improve the reception of its new OS, given the Windows 8 devices that had been announced were looking fairly uninspiring, and pushing its hardware partners to up their game.

Not all hardware makers felt the same way: others such as Acer advised Microsoft to "please think twice" about making its own slates. Microsoft indeed admitted that releasing its own hardware in this way could affect the commitment of partners to the Windows platform, and yet still it continued.

Google has also gone some way down this route, partnering with Asus to bring out its own 7-inch tablet. It's not quite the same as Microsoft's Surface situation, in that Google essentially repurposed an existing Asus design for its own needs, but it also has similarities in that Google's strength in mobile is in software, not hardware.

More recently than that, Google launched the Chromebook Pixel, in a move that seemed like it was driven by the same motivations that led to the Microsoft Surface – an attempt to address the uninspiring hardware design that had beset its OS. Is it a perfect laptop? Not by a long shot, but it's a great start towards it. (And let's not forget that software isn't even Google's core business – that's ads, not software.)

But what inspired Google and Microsoft to make this dramatic shift?

The roots of the transition can be traced back to Amazon, and the launch of the Kindle Fire. At a time when virtually every other notable Android tablet came with a premium price tag, Amazon swept with a cut-price offering in and stole millions of sales.

The Fire wasn't the first cheaper alternative Android tablet on the market (Samsung had the 7-inch Galaxy Tab at the time), but it was the first one to really take off.

The Fire line's popularity showed that, in the minds of device buyers, the right combination of price and brand recognition can go a long way, even if hardware isn't what your brand is best known for — an online retailer such as Amazon is particularly well-placed to take advantage of sales trends if it can get the device mix right.

One of the problems for traditional hardware vendors is that they are often locked into long, well-established contracts with various software vendors, contributing to the necessity for incredibly long lead times to go from a product's conception to sale on the shop floor. Amazon doesn't have any such concerns.

What Amazon does have though, as does its rival Google, is a huge resource of buyer behaviour data to inform what they do next from their respective core businesses of ads and retail — another area where traditional hardware players are a disadvantage to their newer rivals.

When a heavyweight brand — be it Google, Microsoft or Amazon — with impressive command of their supply chain and insight into consumers' buying habits start getting into the hardware business, device makers' alarm bells should start ringing.

Innovators or imitators?

Of course, sufficient time has passed for traditional hardware makers to have noted the success of the Fire and Nexus 7 and start producing similar devices, but it's unlikely few will receive reviews or a buying reception like the Nexus or Fire as, quite simply, the category is not particularly new or novel anymore.

Hardware makers seem fixated on attempting to cash in on a thriving category, rather than define the next one. What they need to do is be more adventurous with their hardware to create a worthwhile balance of features, design, performance and price. Someone has to take the leap first, just as Amazon and Google did with their low-cost, high-spec 7-inch tablets.

And while HP, Dell or any other device maker pursuing a strategy of making me-too devices will do well enough to keep paying the bills, it won't win the hearts and minds of consumers, it won't spark the next category revolution and it won't push rivals to try harder either.

It seems that for that, we now have to look to the likes of Amazon and Google to see what's coming next in terms of mobile computing, and if this trend continues the hardware giants of today will be relegated to grinding out the dullest devices of tomorrow.