Paladin's anti-hacking browser extension looks like snake oil, experts say

(Image: ZDNet)

Over the years, we've seen a lot of questionable security products from headstrong startups who say they want to save the world but cause more problems than they're worth.

Security "snake oil" is a real problem. These are the apps, products, or services that offer little worth or value but profess to fix a problem. They're harmless enough if nobody gets hurt, but the people who seek out safety and security are often the ones who need it the most. Flawed products can put them in greater danger. In some parts of the world, evading surveillance can be the difference between life and death.

Read also: Online security 101: Tips for protecting your privacy from hackers

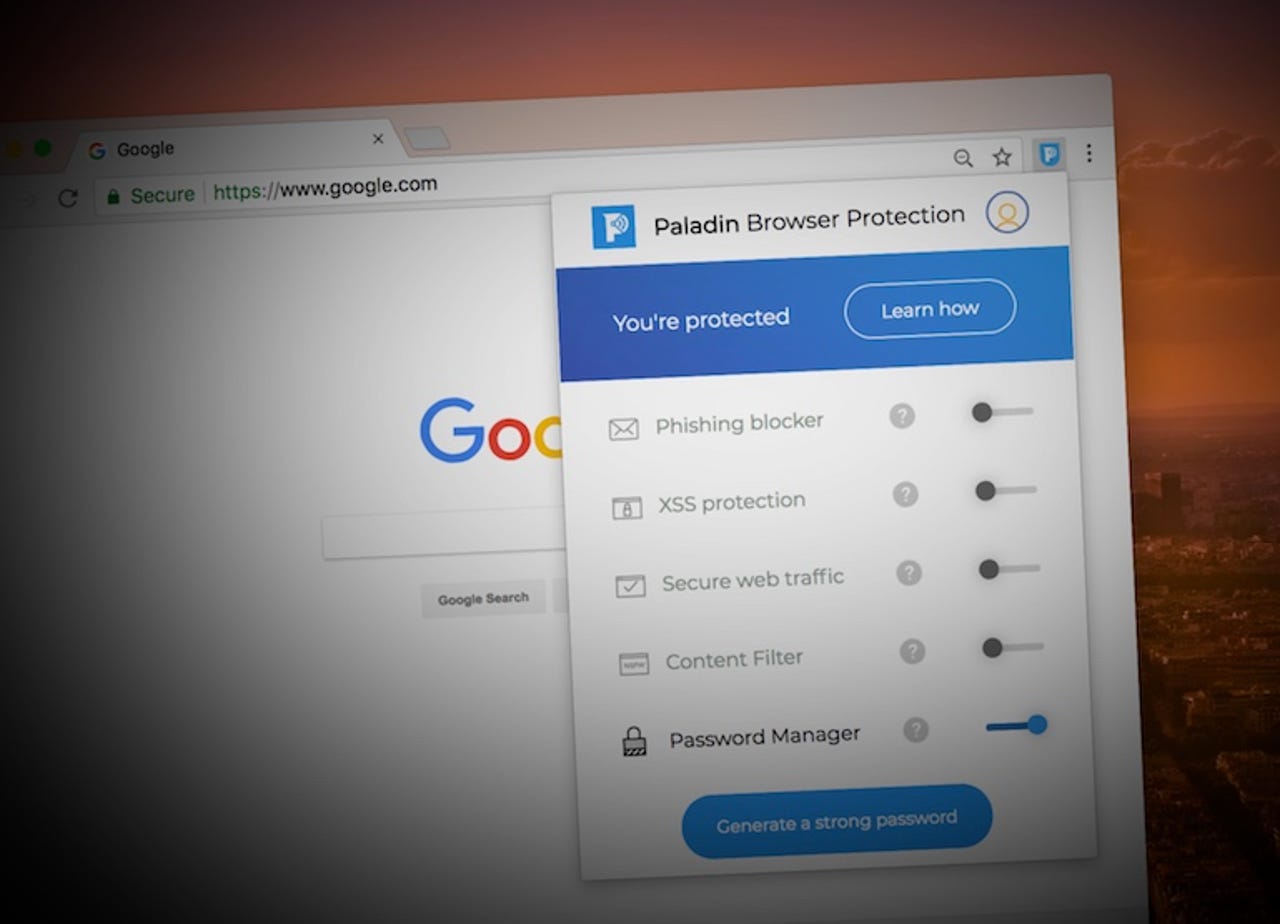

The latest purported security solution comes from Paladin, a year-old startup, which claims its newly launched Chrome extension can, according to a blog post, "helps consumers avoid getting hacked entirely." (This is an immediate red flag, as no security expert would ever make that claim.) The free extension promises to block phishing attempts, secure public Wi-Fi connections, and prevent cross-site scripting flaws that can trick a user into handing over sensitive information.

Plus, the company said that it has yet to conduct an independent security review, but it plans to, including a a SOC 2 audit on its systems, later this year -- after its release.

For any security-focused product, saying "not yet" to an audit is bad enough. We dug in deeper, enlisting security researchers who came to the conclusion that the extension is flawed in both design and implementation, and it may end up putting users at risk.

"These guys feel like a bootstrapped startup," said John Wethington, a security researcher, who reviewed the extension's code for ZDNet.

Since we first got our hands on the pre-launch version last week, the version at Tuesday's launch contains the almost exact same code as the extension that was analyzed. Both versions contained major issues that cast doubt on the effectiveness of the extension.

Here are some of the highlights.

The extension's password manager uses AES-256 encryption, a strong and widely used standard. Wethington found that passwords were further scrambled using a static salt value, meaning every password is hashed in the same way. Using dynamic salt unique to each user is widely seen as more secure.

Like any encryption standard, a good random number generator is required to fend off brute force attacks that can decrypt data. But the password manager uses Chance, which includes the Mersenne Twister, which is not cryptographically secure, and has been phased out of most modern apps and services. Chance's developers warn on the project's website that the library should "probably not be used for any cryptographic applications."

We reached out to Paladin's co-founder, Han Wang, prior to publishing to allow the company to comment.

Wang said the Chance library is used "only in assisting in generation" of passwords, and that the data generated by the library is "still much more resilient to a brute force attack than user generated passwords of the same length."

"The salting was implemented in the beginning when we (sic) explore additional use of hashing for collision detection, however, we ended up pushing that functionality for a future product update and the salted key became mostly used for AES256 encryption," said Wang, disagreeing with Wethington's findings. "Since we reduced our hashing of passwords, there was no longer a need for dynamic salting of passwords."

In the past year, researchers have shown they can easily predict the outcome of the Mersenne Twister, opening any application or service that uses the random number generator ripe for attack.

Wethington also found that the master password used to encrypt the password manager is fully decrypted, a risky technique that exposes the password rather than safely checking its hash.

Paladin said this was an "implementation detail (sic) which we wanted to encrypt the password blobs with the user supplied strings," and that the company may change this in an upcoming update.

Paladin says it can take a user's unsecured Wi-Fi protection feature -- or any internet connection -- and encrypt it, "leaving you clear of any danger." The feature is essentially a proxy, by funneling your unencrypted data through an encrypted pipe to the company's servers and back again.

In doing so, you have to trust the company with all of your internet traffic and hope they don't misuse it. Users' internet traffic flows through a server running the widely used open-source Squid Proxy.

Will Strafach, a security researcher who reviewed our findings, said this technique was "incredibly risky," because the extension sends all of a user's sensitive information.

"It's something you should only ever do if you have a high grade hardened infrastructure and users are 100 percent aware of what they're trusting the company with -- and it doesn't seem like they make this clear at all," he commented.

Wang said the majority -- but not all -- of user's sensitive traffic are HTTPS-encrypted, "so we do not have access to their plaintext."

Read also: The myth of responsible encryption: Experts say it can't work (CNET)

In processing such sensitive user data, we asked about recent changes in privacy regulations -- the EU's new GDPR data protection law, which has the capacity to fine companies up to four percent of the firm's global revenue for the previous year. The company said it is "not offering the extension in the EU at this time." A colleague in our UK office was able to install the extension without any issues. The company's own privacy policy references that user data can be transferred outside of the EU to be processed by the company.

Digging further, Wethington also found that the extension's proxy feature has no backup in the event of an outage. If the company's website goes down or suffers a denial-of-service attack, the user's browser will appear offline.

Wang said that the company uses several Azure-based, geo-load balanced servers behind two proxy endpoints to spread the load across its users.

Wethington also found that the extension's phishing protection feature, which relies largely on OpenDNS' phishing service, could put user's browsing data at risk. Paladin's phishing feature checks a suspect domain against OpenDNS, then scrapes the domain from the browser's address bar, and submits it to a Firebase store run by the company -- which Wethington said effectively crowdsources a blacklist of suspect domains using OpenDNS' data.

Paladin said it does "not keep anything" unless the user submits a phishing email report. Wang said that the company will "only process emails online as the user reads them so we only access the bare minimum of data to make a dissertation on phishing emails."

We also found hardcoded Firebase credentials in the code at the time of launch, allowing anyone to access the company's account. (We did not check, as that would violate US hacking laws.)

Wang said these were client-side credentials, which the company uses "to provide real-time sync of user data across their browsers and also lock down permission per user for isolation."

The domain whitelist also contains several advertising and media networks, allowing ads to appear in the user's browser. While not an issue in its own right, the extension has no mechanism to block malicious ads, leaving the user at the mercy of the ad networks to weed out malvertising. Last year, malvertising reached record levels, according to reports.

Paladin said its product was "never advertised" as an ad-blocker, and it said "most" ad networks do not inject malicious code from its own domains.

Any secondary load from a non-ad network "would be censored by our proxy network same as accessing the malicious page directly," said Wang, but did not say how.

The cross-site protection (XSS) feature uses a regular express (regex) policy, designed to prevent the browser from running code that contains certain characters. Critics have long argued that using regex policies can't always protect against XSS attacks -- especially if the code is obfuscated.

Paladin said it was confident that its regex policy was enough to prevent XSS attacks.

We also found a line of code that pointed to an open, unprotected Amazon S3 bucket, which anyone could access. There was no sensitive data on the bucket. Paladin said this was "by design" to test if a user is behind a captive portal, such as a Wi-Fi registration page.

Suffice to say, the extension has concerning issues. What's even more striking is the backward approach to taking its own product seriously. Instead of taking the time to refine the extension, the company launched without any meaningful security checks.

Read also: Password managers: A cheat sheet for professionals (TechRepublic)

"Unfortunately for unsuspecting users it is easy to fall prey to marketing from products that make wild claims about their capabilities," said Wethington. "What is more disconcerting is the vendors attempts to defend some of the practices they've adopted when they clearly are not in the best interests of the end users security and go against industry standards and best practices established in the trenches of today's threat landscape."

No doubt, the extension had promise. But security apps are notoriously difficult to build, and will never be perfect, lending them to the heaviest criticism over the smallest weakness. Even some of most highly regarded apps for their build quality can suffer at the hands of the simplest bugs.

Paladin is poorly thought-out, and risks giving its users either a false sense of security -- or worse, putting their data at greater risk.