Cyber espionage 'extremely dangerous' for international trust: Kaspersky

International agreements are needed to limit online espionage and develop an "international cyber-resilience strategy" to address the threat of digital attacks on critical infrastructure, according to Kaspersky Lab chief executive officer and chairman Eugene Kaspersky.

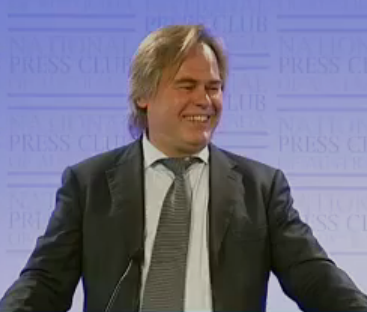

The ease of conducting cyber espionage is "extremely dangerous" for international trust, Kaspersky told the National Press Club in Canberra on Thursday.

"If nations don't trust each other in cyberspace, the next step is to separate it [into] two networks. One public network, and one enterprise and government. It's an obvious step, and I'm not the first man to talk about that," he said.

"I'm afraid it's a very bad option ... governments and enterprises will be happier, because they have a secure, unhackable network. Good news? No. First of all, there will be much less investment in the public segment. Governments and enterprises leaving the public space means that the budget's running away. Second, do you have enough engineers to build an Australian national network?"

Kaspersky called for more education for network engineers and security specialists several times during his speech.

He also reinforced his oft-repeated message that attacks against critical infrastructure have the potential to cause collateral damage, as systems other than the intended targets can become infected, and that once a cyber weapon has been deployed, it can easily be reverse-engineered and used by others.

"Unfortunately, the internet doesn't have borders, and the attacks on very different systems somewhere far, far away from you in the very 'hot' areas of this world — maybe in the Middle East, or somewhere in Pakistan or India, or in Latin America, it doesn't matter — they have the very same computer systems, they have the very same operating systems, the very same hardware," he said.

"Unfortunately, it is very possible for other nations, which are not in the conflict, will be victims of the cyber attacks on the critical infrastructure."

Kaspersky cited the examples of American oil company Chevron reporting that its networks had become infected with Stuxnet, the malware originally targeted against Iran's uranium enrichment program, and of Stuxnet reportedly being found in the control network of a Russian nuclear power station whose network was supposedly physically separated from the internet.

"Because cyberspace is exactly the same in all the nations, I think that there is no place for national cyber-resilience strategies," he said.

One key problem is that different government agencies tend to look at cyber espionage and attacks through different lenses.

"Departments which are responsible for national security, for national defence, they're scared to death. They don't know what to do," Kaspersky said.

"Departments which are responsible for offence, they see it as opportunity. They don't understand that in cyberspace, everything you do, it's a boomerang. It will get back to you."

Stilgherrian travelled to Canberra as a guest of Kaspersky Lab.