Blue screen of death? iPhone freezing? Blame particles from outer space

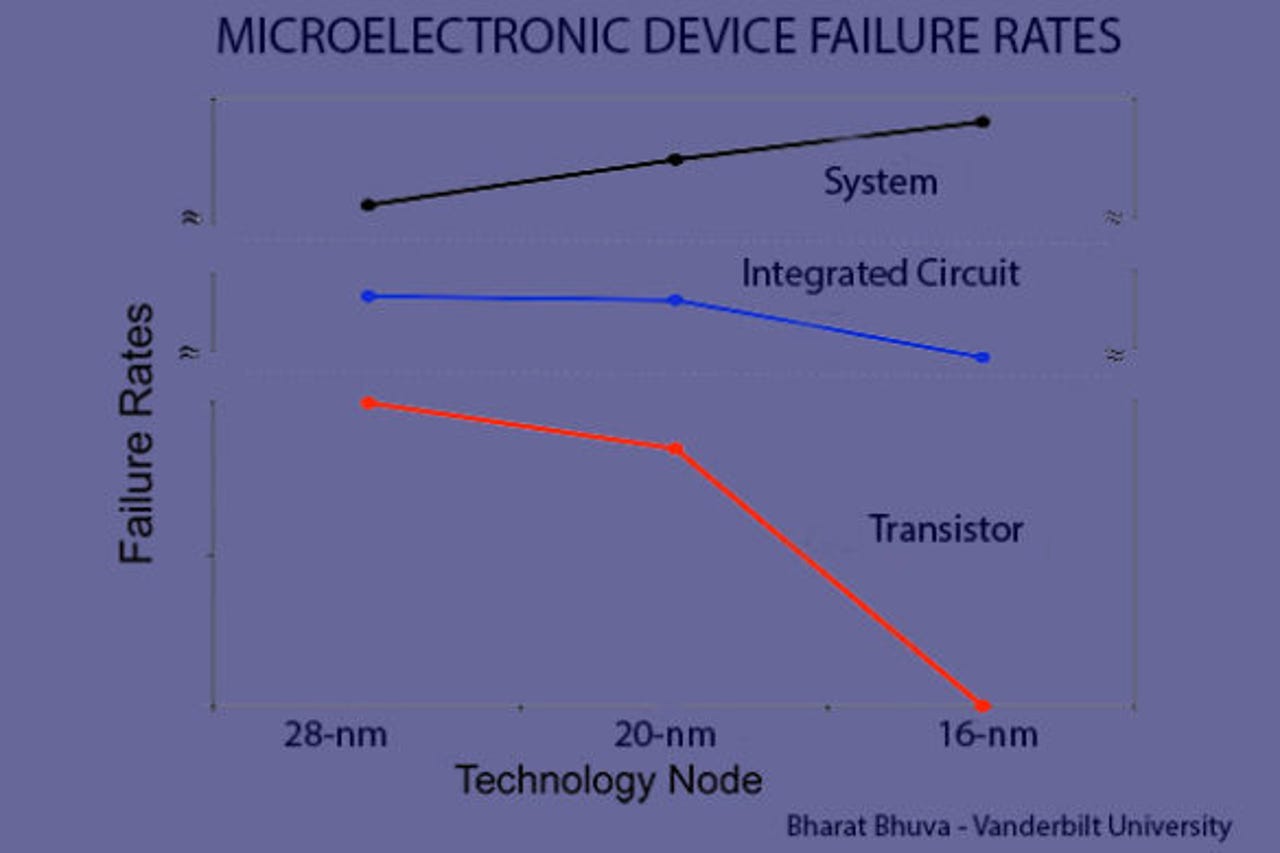

This graph shows the trends in 'single-event upset' failure rates at the individual transistor, integrated circuit, and system or device level for the three most recent manufacturing technologies.

Electrically charged particles from outer space may be to blame when our electronic devices crash unexpectedly.

According to Bharat Bhuva, a professor of electrical engineering at Vanderbilt University, many unexplained glitches that force a reboot could be the result of electrically charged particles generated by cosmic rays from outside our solar system.

Once the rays reach Earth, they create "cascades of secondary particles including energetic neutrons, muons, pions and alpha particles", which are powerful and plentiful enough to trigger a glitch in electronics transistors.

Bhuva is a member of a group that has received funding from major chip makers to study the effects of radiation on electronic systems. Their most recent work explored the effect of cosmic rays on current generation 16nm FinFET 3D transistors.

Backers include Altera, ARM, AMD, Broadcom, Cisco Systems, Marvell, MediaTek, Renesas, Qualcomm, Synopsys, and TSMC. The group has also studied the effects on 20nm and 28nm technology.

"The semiconductor manufacturers are very concerned about this problem because it is getting more serious as the size of the transistors in computer chips shrink and the power and capacity of our digital systems increase," Bhuva said.

"In addition, microelectronic circuits are everywhere and our society is becoming increasingly dependent on them."

While these subatomic particles aren't known to be dangerous to humans, they can wreak "low-grade havoc" on electronic gadgets by, for example, triggering a 'bit flip' where a 0 is flipped to a 1 in memory. These non-destructive and soft errors are called single-event upsets, or SEUs.

It's difficult to trace errors back to these crashing particles, but they're a serious enough concern for NASA to use a system to counter the chance of their causing a failure in equipment it sends to space.

One apparent SEU Bhuva points to was a Qantas flight from Singapore to Perth in 2008 where an avionics system glitch disengaged autopilot, resulting in the aircraft dropping 690 feet in 23 seconds. Another example occurred in 2003 when an electronic voting machine in Belgium experienced a bit flip and added 4,096 extra votes to one candidate.

The likelihood that an energetic particle causes a bit flip has increased because today's smaller transistors require less electrical charge to represent a logical bit, according to Bhuva.

While the new 3D architecture is less prone to SEUs than 2D chips and failure rates at the chip level have dropped, Bhuva notes that the increasing total number of transistors in new electronic systems has caused the SEU failure rate per device to continue to rise.

For the 16nm chip study, Bhuva and fellow Vanderbilt researchers took integrated circuits to Los Alamos National Laboratory's Irradiation of Chips and Electronics (ICE) House and blasted them with a neutron beam to see how many SEUs the chips experienced. They measured the chip's failures in a unit called FIT, or failure in time.

The results of the study haven't been released due to proprietary restrictions, but it's noted that most electronic components have FITs measured in the hundreds and thousands.

"Our study confirms that this is a serious and growing problem," Bhuva said. "This did not come as a surprise. Through our research on radiation effects on electronic circuits developed for military and space applications, we have been anticipating such effects on electronic systems operating in the terrestrial environment."

Bhuva also said only the consumer electronics sector is lagging behind in addressing susceptibility to energetic particles. The aviation, medical equipment, IT, transportation, communications, financial, and power industries are taking steps to address it, he said.

Shielding electronics from these particles would need 10 feet of concrete. However, as Bhuva notes, NASA's answer involves processors that have been designed in triplicate, allowing them to validate each other's results.

"The probability that SEUs will occur in two of the circuits at the same time is vanishingly small. So if two circuits produce the same result it should be correct," he said.