Computer simulation enters the AI age: the Altair story

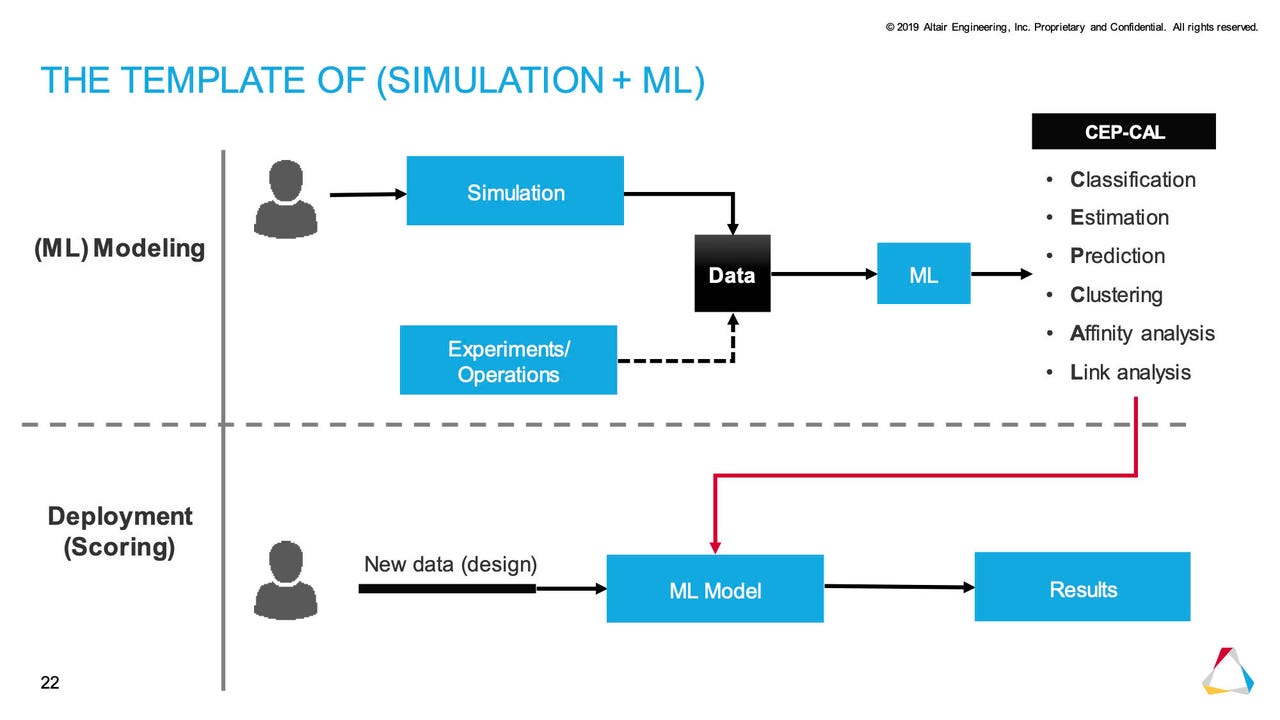

Slides from a talk this year at Altair's tech conference by chief data scientists Mamdouh Refaat. Data that typically is gathered in the real world to inform engineering choices can be supplemented by data created inside a simulation.

"I don't need the money, I wouldn't be doing this if it wasn't really intellectually interesting for me."

Jim Scapa, founder and chief executive of software maker Altair Engineering, was explaining over a lunch of Italian food recently why, at age 62, he's working harder than he has ever worked in his life.

Scapa certainly wouldn't stick around merely to enjoy the slings and arrows of Wall Street investors. Although Altair's shares, traded under the ticker "ALTR," have doubled since the stock's debut on Nasdaq on November 1st, 2017, the stock has had some wrenching ups and downs. Investors have periodically worried that his ambitious M&A strategy to transform the company via artificial intelligence may be leading Altair astray.

Altair stock is up 32% this year, slightly less than the Nasdaq Composite Index.

"I had my training wheels on as a public CEO, and it went very well for the first six months or so," Scapa told ZDNet over lunch in Manhattan. Things did go very well right after the IPO, then came the grumbling.

The tension, in short, comes from the fact that most people are not sure what artificial intelligence is supposed to do for software broadly speaking. Scapa has a vision, and it requires some faith on the part of investors.

Scapa, a mechanical engineer by training, who also earned a masters of business administration from the University of Michigan, has spent 35 years building Altair into one of the preeminent companies in computer simulation. Its software dominates Detroit's design of automobile chassis and systems.

The common name for the field is "computer-aided engineering," or CAE. This is the process of taking models of cars or other objects that have been drafted in a CAD/CAM tool and simulating how they will behave in the real world, things such as the airflow around a vehicle as it moves through space, or the consistency of materials in a built object as that object ages.

Artificial intelligence is a new, emerging part of that. Machine learning, especially deep learning, can take in tremendous amounts of data and use it to discover a function that approximates a solution to a problem. An engineered object can live inside of a simulation on the computer that has a constant connection back to reality. It's rather like how Neo in The Matrix has a real life on earth but also a life as an avatar inside the machine. It's the notion of a "digital twin," and it has been expressed by many in the design software business for years as a kind of Holy Grail.

Altair co-founder and CEO Jim Scapa.

Scapa's novel take is there will be both "simulation-driven digital twins, and data-driven digital twins," as he puts it, forms of objects that take shape as the computer is fed with data and as new data emerges from simulations.

Data lets machine learning refine a design, in some ways more objectively than a human designer might engineer one. Feeding the machine with simulation data, in a constant dialectic between design and simulation, can speed up the process of refining designs.

That dialectic of design and simulation is pervading the world thanks to AI, Scapa believes.

"We are at a moment in time where for many things that we do, the algorithms are driving decisions," is the way Scapa broadly views the landscape of society, not just engineering. "For me it's all about how algorithms are assisting humans to make decisions," said Scapa.

To broaden Altair's reach into every aspect of algorithms, Scapa has been on a buying spree, buying thirty companies since founding Altair in 1985. The immediate advantage of taking Altair public after decades private is that it filled Altair's coffers. Cash and equivalents on the balance sheet have surged to $247 million in the September quarter from just over $17 million before the IPO. (Altair's balance sheet was boosted by a follow-on offering of stock last year.)

Some of the deals have been just fine with investors, such as SimSolid, a company Scapa purchased in October of last year after a six-month review process. It can perform simulations of engineered objects without first breaking the computer model down into simple parts. That can dramatically speed up simulation time. Scapa calls SimSolid "the product of one brilliant engineer from Belarus, a guy who had figured out some really difficult physics," referring to SimSolid co-creator Victor Apanovitch, a former professor at Belarus Polytechnic University.

Other deals have not gone down as well, such as the November, 2018 acquisition of startup DataWatch for $176 million in cash, Altair's largest deal ever. In order to manage all the data that is going to be fed to machine learning systems, Altair needs to bulk up on data science. DataWatch, which began life the same year as Altair, started as a maker of IBM-compatible computer terminals, but later moved to making only software. In particular, it spent years building and buying enterprise programs for so-called business intelligence, things like data reporting, particularly for the financial services industry. DataWatch is a data analytics and data science pioneer that to Scapa fits very well with Altair's simulation capabilities.

Many didn't see it that way. "The stock dropped right after we announced the deal," he recalled. Investors felt uncomfortably surprised. They wanted Scapa to keep steadily building a very predictable business of simulation. "They wanted me to keep buying solvers," he said, using the industry vernacular for compute engines that represent different physics problems and that can be continuously added to the company's platform in predictable ways to expand its utility. They didn't want him going off on quixotic quests.

DataWatch was a company with a checkered past that some investors were already wary of. Richard Davis, a stock analyst with Canaccord Genuity who follows Altair's stock, this past spring wrote that "We have too much experience with DataWatch's epic mis-execution to believe that this purchase was anything but a mistake."

"The lesson I learned is that I have to do a much better job messaging this, sometimes, so people see where we are going," Scapa told ZDNet. He seemed undeterred, however, noting, "We have some very good long-term investors."

Some skeptics have arrived at grudging acceptance of Scapa's method. Canaccord's Davis wrote that despite his objections to the DataWatch deal, "we give Altair's management credit for cleaning house there and then allocating what appears to be a rational amount of employee talent to an effort to grow the business."

Davis likened the potential of Altair to that of Ansys, another publicly traded software maker, whose shares soared 11-fold in the first decade of the new century.

So far, the M&A is adding up to healthy rates of growth. Analysts expect Altair to achieve 14% revenue growth this year and perhaps 11% next year, when it may reach half a billion dollars in sales. "I think it has the potential to be substantially larger and much broader," says Scapa of the simulation market versus what it has historically been.

With ownership of about 45% of the shares outstanding of a $2.6 billion company, and over half the voting power, Scapa, who is also chairman, is in a position to do what he believes he must in spite of the grumbling. The price of an education in the stock market, in his view, was worth it in return for capital. "We were a rocket on the launching pad," before the IPO infused the balance sheet. Now he has rocket fuel to pursue deals, to build out the portfolio.

As a nerd, Scapa can't help but marvel at the frontier of AI and cloud and all that goes with it: partnering with Nvidia for the future of GPU computing; developing tools for NASA's "Pleiades" supercomputer; working with cloud computing giants to design new silicon for AI — all these vistas have the feeling that Scapa and Altair have prospered long enough to participate in an epochal time.

"The future is bright," said Scapa as lunch wrapped up.