Facebook: most flagged photos aren't offensive, just unflattering

Last year, Facebook discovered that the majority of photos its users reported weren't necessarily offensive (violence and nudity); they were just unflattering (poor angle, lighting, or unattractive facial expression). Facebook engineering director Arturo Bejar revealed this tidbit earlier this week in an interview with Neal Conan on NPR. Here's the relevant transcript from the interview:

Conan: And when did you realize that the user's definition of a reportable photo was different from your definition?

Bejar: So we usually sit down with the people who process the reports as they come in, and we like to see what they're doing and what the content that is being reported. And we went to the photos. And we're going for photo after photo after photo, and it was reported for like violence or drug use or pornography. And we're looking at the photos and we're like there's absolutely nothing wrong with that photo. That photo is fine. Somebody — might not be the most flattering photo. And then we noticed that the person who was reporting the photo happens to be in the photo. And so we began digging into the issue from there.

Conan: And so as you started to realize that these are people who were tagged, as the expression goes, in that photograph, clearly, some of them did not enjoy their image.

Bejar: Absolutely. And when you look at the two options that we give you when you see a photo and you don't like how you look in the photo, you can either talk about it in the comment thread for it, in which you're pointing attention to it, you're calling attention to it in front of all of your friends. Or you can hit report. So people were hitting report and were using the available categories to let us know that they didn't like the photo and that they would want to have the photo taken down. But we wouldn't take it down because there's nothing wrong with the photo.

Conan: So how did you decide to adapt your policy then?

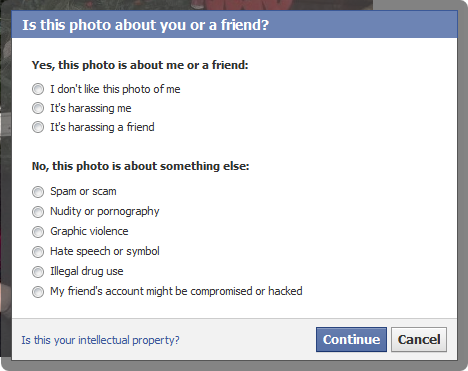

Bejar: So we made it such that when you hit report, we ask you if you're in the photo. And then we ask you if the photo is unflattering or if you don't like how you show up in it or whether you find it harassing or bullying you. And most people say, you know, I don't like how I look in this photo. And in the first version we did of this, we put up a blank message box where you can send a message to the person who posted the photo, usually a friend of yours. And most people faced with that blank box wouldn't put anything in there in which they would, sort of, step out of the fore because they didn't know how to handle that conversation with their friends.

Conan: They didn't want to confront anybody and were uncomfortable and didn't know how many people were going to see that message too.

Bejar: Mm-hmm. Yeah. And so what we did is we were, at that time, talking to somebody at the Compassion Center in Stanford, the Compassion Research Center and - called CCARE. And in talking to them, they were telling us that what triggers your compassion reflex is when you recognize that the other person is experiencing an emotion. So if you notice that they're sad, if you notice that they're happy, if you notice that there's something going on with them, how you engage with them changes. And we tried different pieces of text in that open dialogue box. We put in I don't like how I look in this photo. We tried different messages. And then we allow you to edit before you send it so that's in your voice, but we wanted to facilitate the conversation by putting some default words in. And in doing...

Conan: Some prompts, some suggestions.

Bejar: Absolutely. To prompt some suggestions for people to send a message. And we found that the message that said, hey, I really don't like how I look in this photo, most people would feel comfortable sending that message. And most interesting, most people who receive that message would just go ahead and remove the photo.

Conan: Did they reply back at all?

Bejar: Sometimes they did. Sometimes they didn't.

Conan: And sometimes, did they apologize?

Bejar: Sometimes they did, yes.

Conan: It's interesting because you can sometimes get a flaming email from somebody, and they don't really expect you to write back. But if you do, they will say, oh, I'm sorry. I didn't know you'd take it that way.

Bejar: Absolutely. And as we look at the content and as we've been looking at the space very closely for sometime now, we find that most status updates are photos that people find stressful were not intended to be that way at all, that the person posted the photo because they liked it. They thought it was funny. They didn't notice how the person looked in the photo or they were saying a comment which they thought was clever. And you're and the computer and you post that, and you don't have the - that you cannot see the person's face when you're saying this to realize that what you're saying might be impacting them in some way. And so we could do some work to help facilitate that conversation.

Once Facebook realized it wants to encourage compassion, it updated its "Report This Photo" tool. As you can see in the screenshot above, the first three options are: "I don't like this photo of me," "It's harassing me," and "It's harassing a friend."

Facebook takes down offensive photos, but it can't simply delete photos that someone else finds unflattering. It's up to the person who uploaded a given photo to decide whether he or she wants to take it down. The new options are meant to help start a conversation between the person who finds the photo unflattering and the person who uploaded it. In this way, Facebook can help them reach a resolution, instead of simply ignoring requests to take down the photo in question because it's not offensive.

See also: