Adobe to hold its customers' hands

Adobe has taken more of a hand-holding approach to ensuring that its customers are protected from security threats, but even with a new priority system for patching and a version of Reader that has yet to be seriously compromised, users are still making life difficult for themselves, according to Adobe Systems security guru Brad Arkin.

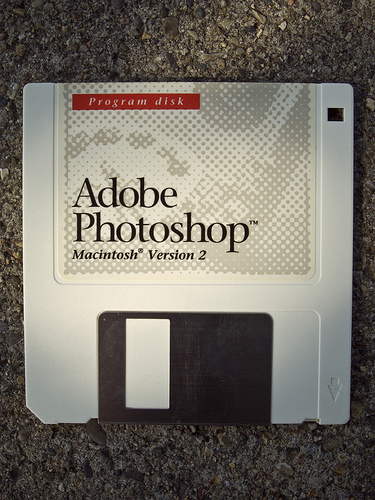

Sometimes users can remain on older versions of software long past their expiry date

(Adobe Photoshop 2.0 image by Michael Carian, CC BY-SA 2.0)

In an interview with ZDNet Australia, Arkin, who now works as Adobe's senior director of security, standards, open source and accessibility, joked that in the past, he would have been rubbing his temples from security worries. Today, however, the company has fewer security problems to contend with. The inclusion of a sandbox in Reader X has helped immensely to kerb the number of exploits that users are experiencing — not a single one has been reported — leaving Arkin and his team to worry about the older versions of Reader.

What this has led to is a focus on patching and helping users and administrators know what they should be doing. Up until now, Adobe has been classifying security patches as critical, important, moderate or low severity. However, Arkin said that while this does a fairly good job at describing the worst-case scenarios, it doesn't give administrators an idea of whether there are patches so important that they need to drop everything to apply them, or whether the unlikelihood of them occurring means that they can wait.

For example, a "critical" vulnerability that exploits huge files in one of Adobe's video-editing suites would realistically be of lesser priority than an "important" vulnerability that affects Flash Player or Reader and is known to be a target of attackers at the time.

To help administrators, Adobe has implemented priority levels to give an idea of how urgent an issue is.

"We tried to make it idiot proof. The world always builds a better idiot when you do that, but we're labelling them priority one, two or three."

Priority one, or "drop everything", patches solve known exploits that are presently in the wild and have a high risk of being targeted. Priority two, "these are a good idea", patches are a step down from that, and Adobe recommends installing them within 30 days. Priority three, "we've never seen an attack", patches are for exploits that will likely be obscure, and can almost be ignored. For example, a priority three patch might include a bug that requires users to do something, like download a 2TB video file via email — a possible attack vector, but extremely unlikely to be used by a hacker, as there are more credible methods of entry.

Adobe has gone further with its hand holding; it has improved its update manager to the point where administrators can upgrade to Reader X with the same amount of work that it takes to issue security patches for Reader 9, which has a history of being successfully attacked.

This leaves fewer excuses for backwards users to continue to use Reader 9. However, Arkin said that it simply wouldn't be fair to force users to use Reader X, due to the five-year support model that was promised to Reader 9 users at the time of deployment.

"As frustrating as it is for someone to get attacked when they're using version 9 — it's like this unnecessary thing, because they could have been running [Reader X] — we don't know their business, and we don't know all the choices they're making."

As an example, Arkin highlighted the problems that a corporate account might have with a large number of copies of its products.

"If you roll out Reader and Acrobat out to 100,000 machines, that's a huge expense. Usually, that's a two-year cycle to plan for and roll it out, and they don't want to have to move versions every single time. We would encourage them to really study and revisit their previous decisions ... [because] the world has changed," Arkin said. He added that companies would need to make the decision, since forcing them to the latest version through automated updates would be akin to installing malware.

"My life would be a lot easier if everyone was running [Reader] 9, but it's not up to us. We need to live up to our commitments. If we were to just change the rules halfway through, that would really make life hard for these guys.

"From our engineering team's perspective, it's a pain in the neck. We would rather just have one version, and that's that."

While there are no existing plans to shorten the duration of Adobe's support model, Arkin didn't rule it out as a possibility in the future.

"The support model was the same for [Reader X] as it was for previous versions, so I'm not aware of any changes [or] plan for that sort of stuff, but you never know; the world is changing fast, so we'll see."