Adware, 2013-style, still thrives

I know I haven't thought about adware in many years. Around 2000 adware was a new and troublesome category of software. Programs like Gator pretended to be legitimate and it wasn't clear, especially in the fairly early days of the Internet, that what they were doing was legal. It was because of this iffy status that the euphemism PUP, for Potentially Unwanted Programs, was created by the security business.

But now, as demonstrated by Harvard Business School Professor Ben Edelman and Wesley Brandi, the software lives on, funded by the sales of ads for legitimate advertisers through legitimate ad networks.

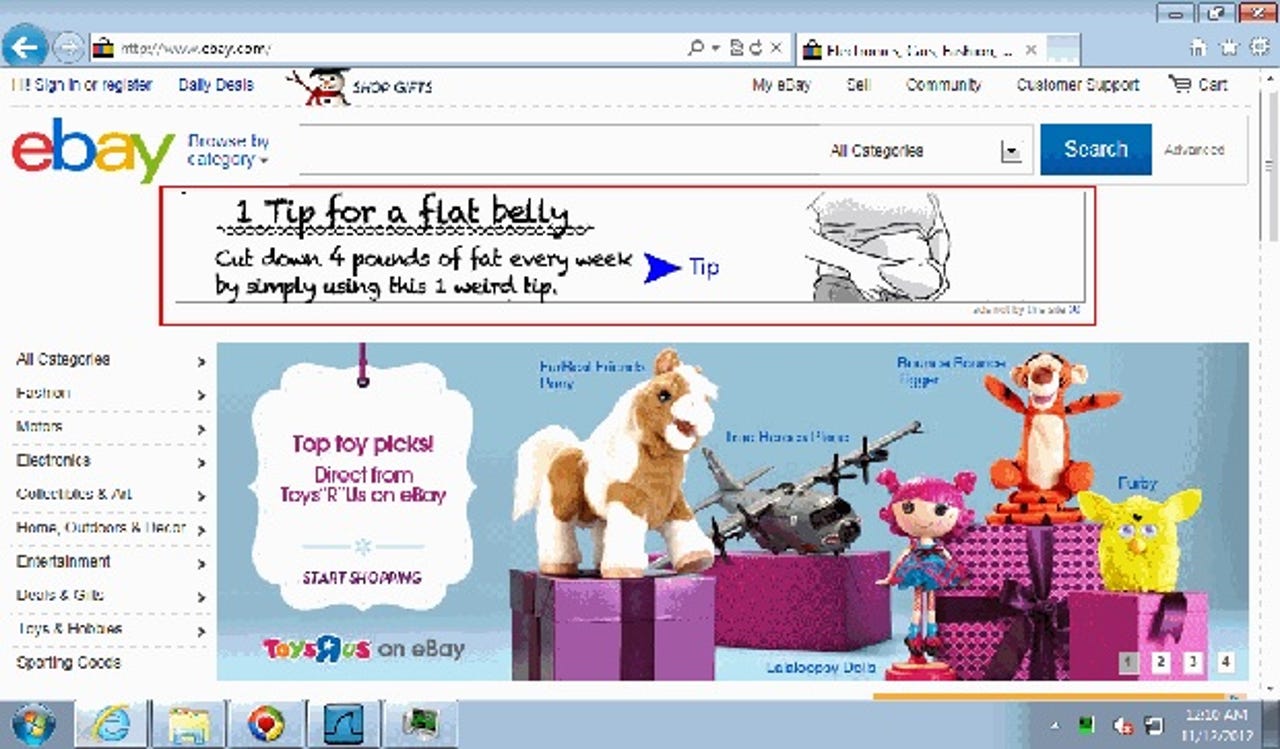

These ad injector programs work in your browser, usually on Windows. Edelman and Brandi say that "in many instances injectors modify Chrome and Firefox in addition to Internet Explorer." They insert ads into web pages as they render. Consider this example:

Note that, in the bottom right, the ad says "ads not by this site". The researchers found ads injected into pages, including the Google home page and Wikipedia, which never allow advertising. Injectors also insert advertising that the site might find objectionable, such as the one above, or show ads from direct competitors, such as this Best Buy ad injected into Dell.com by the Coupon Companion injector.

How would you get such program in your browser? When you get one of those fake "You need to update your Flash Player" popups you might, or when you install free games that you got from some guy in a sleazy, dark corner of the Internet. These programs are often bundled with adware as a way of monetizing them. There's no simple way to know how to avoid them other than to use your common sense and, if you see a phrase like "shows ads when you are online" you should close the browser and run the other way.

Because the ads are usually bought through a long affiliate chain, the actual advertiser may be unaware that the ad is being displayed using ad injection. But sometimes it's simple; Edelman and Brandi found one AT&T ad served directly from AOL's Advertising.com to Sambreel's Webcake injector and into a YouTube page.

Edelman and Brandi performed extensive research of the ad networks who buy and sell ads delivered by injectors. They set up test systems with network loggers that allowed them to observe the entire chain or brokers, agencies and affiliates from the advertiser to the injector. The results tables include some well-known names.

The nearby image shows a more typical and convoluted chain of ad buying. Edelman and Brandi describe it thus:

…the Peachfuzz injector used an Akamai ad server to pass an injected impression to Serving-display.com which returns Z5X tags passing the impression through the App Nexus marketplace. Next App Nexus returns DoubleClick tags with account code N4694.Beep346, yielding tags from Goodway Group, a digital marketing service provider. Finally, Goodway Group returns an ad for Chevrolet.

When things get this complicated, it's no surprise if Chevrolet, or even some of the intermediaries, are unaware that the ad is being served by injector. The same is true if the buyer is going through a purportedly respectable outfit like Advertising.com.

The best argument you can make for these companies is that they're another way to make the advertising market more efficient. Even to the extent that you can make that argument, it's clearly outweighed by degradation injected ads cause in the user experience, the compromise of the site's image and message, and dishonesty of the system through which they are sold.

The reason these injectors exist is that ad networks are willing to buy their ads, either directly or indirectly. As Edelman and Brandi show, some ad networks have done a good job of blocking out injected ad traffic, some embrace it, and some don't want it, but aren't trying hard enough to stop it. After reports like this, perhaps advertisers will be less willing to accept the business.