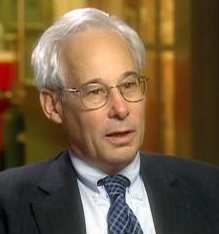

Berwick emerges to ask if we can all get along

He got a chilly reception, one executive asking pointedly when the Administration would stop painting the industry as villains. (Maybe when they stop acting like villains?)

Berwick was given a recess appointment in the summer, but the President has now resubmitted his name to the Senate, hoping that the fait accompli of his being in office might assuage some of the anger coursing through the health industry.

Fat chance.

Critics have kept up a steady drumbeat against health reform since the act was passed, with Republicans promising to either repeal the law (not possible before 2013) or at least defund the agency Berwick heads (possible with a Congressional majority but unlikely).

Neither side of the aisle will be happy about Berwick's latest performance. Conservatives because, as the questioning indicated, they have invested heavily in vilifying him as a secret socialist. Liberals like Philip Longman because, as they note, socialism might work better.

The intractable problem remains, as ever, that wellness care costs less than hospital services. Longman says giving wellness care to every American would add 1% to the total health care budget, but that money would come back in the form of less service utilization down the road.

Conservatives call giving care to everyone socialism. They seem to prefer a feudal system where the lords and ladies of the elite get all the Botox and tummy tucks they want while the rest get only what they themselves are able to pay for.

Berwick stands for something between socialism and feudalism, a system where everyone is covered under something like a Kaiser health plan, while insurers and governments keep a thumb on the customer's side, mandating cost controls for services paid for out of the common pool.

They don't actually oppose high-end care for the financially endowed. They just know it has minimal impact on the basic metric of society health, and it is Berwick's insistence that we look at health care as a system, not just a collection of interests, that will always make him controversial.

Looking at health care as a system requires judgements, which always abridge someone's freedom, even if only that of con artists.