Does software piracy lead to higher malware infection rates?

The rationale behind their claims is fairly simple - users relying on pirated copies of software also do not have access to the latest, often critical from a security perspective, updates issued by the vendors, and are therefore susceptible to client-side vulnerabilities.

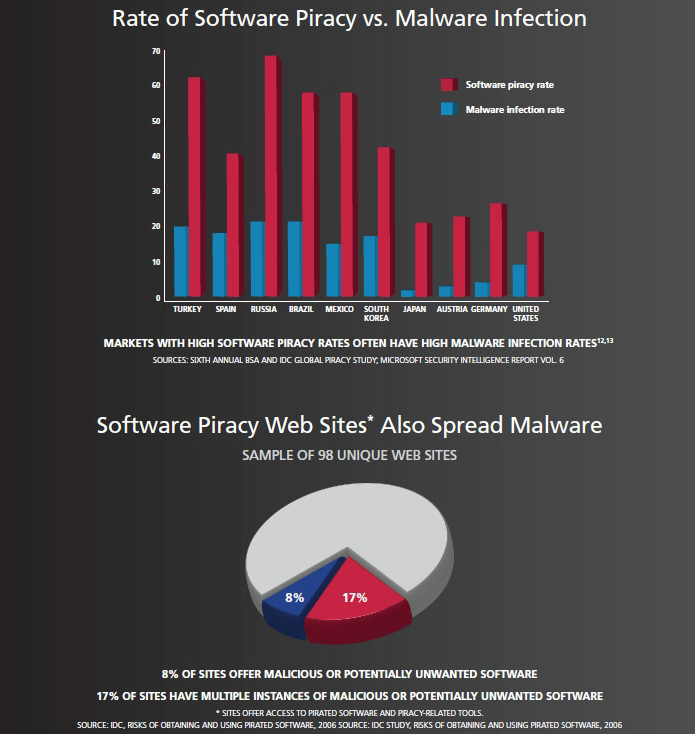

How biased are BSA's claims, or are the report's claims in fact real, emphasizing on how millions of users relying on pirated Windows copies are usually the first to become part of a botnet?

Infection distribution data for the poster child of patch management failure on a global scale, Conficker, speaks for itself, at least in respect to the report's claims. At the beginning of the year, Symantec also made a connection between the high piracy rates of the most affected countries, and contributed their high infection rates to the user's inability to obtain the released patches ":

On October 20, 2008, Microsoft rolled out an updated Windows Genuine Advantage (WGA) system to help combat the high rate of piracy of its Windows platform. One of the side effects of this policy is that people using illegal copies of Windows will be more likely to disable automatic updates from Microsoft. The fear is that a subsequent update may adversely affect their experience with Windows in a similar way the "black screen" that affected many users in China operating illegal copies of Windows. Without automatic updates, it is highly unlikely that many of these users are manually installing critical updates such as MS08-067.

The same infection distribution was confirmed by IBM's ISS in April, once again highlighting some of the very same countries known to have high software piracy rates as main Conficker targets.

Despite the obvious connections, susceptibility to client-side vulnerabilities isn't entirely driven by the software piracy rate. For instance, despite that vendors of ubiquitous applications release free patches to everyone, millions of end users are not applying them (Research: 80% of Web users running unpatched versions of Flash/Acrobat), with evidence of the practice streaming on a monthly basis (Secunia: Average insecure program per PC rate remains high) based on data from multiple vendors.

Why is this "the patch is there, but we don't care" mentality so common among end users? It's because end users, next to certain network administrators, are still failing to understand the current threatscape and the simple fact that cybecriminals are more interested in targeting specific client-side vulnerabilities than OS related ones. Combined with the fact that according to Qualys, application patching is much slower than operating system patching, once again demonstrates why are web malware exploitation kits using outdated exploits so successful in general - they've found a sweet spot and a window of opportunity to take advantage of.

What do you think? Does software piracy lead to higher malware infection rates, beyond the success of the Conficker botnet? What use are Microsoft's critical patches to the millions of users relying on pirated Windows copies, which would ironically join a botnet and start attacking those using legitimate Windows versions? Should Microsoft care?

Or is software piracy irrelevant to the infection rates considering the fact that millions of users still haven't applied the free patches released by their vendors months ago?

Talkback.