IDF 2010: Lizards, lightbulbs and tepid showers

It's Intel Developer Forum 2010, and time to make the annual pilgrimage to the Moscone Center in chilly downtown San Francisco to see what the chip company's been up to this year. Monday, IDF Day 1, will see the big guns of Otellini and pals rolled out to talk about Sandy Bridge and much else - but Sunday was an altogether more oblique affair.

The Intel Developer Forum Day Zero is what most other organisations would call press day, the day before the conference proper when attending journalists are briefed on what's going to be happening. In the past, that's involved a wide range of research areas from within Intel – not this time.

In June, Intel announced its Interaction and Experience Research group, a new lab headed by the company's alpha ethnographer, the undeniably Australian Genevieve Bell. This group does the normal usability and operability work that any self-respecting technology company does, but Intel being Intel and Bell being Bell, it's not done in a normal way. Day Zero was all about exposing us to that.

The day was in two parts – a showcase of various ongoing projects, which I'll write about later, preceded by a showcase of Bell.

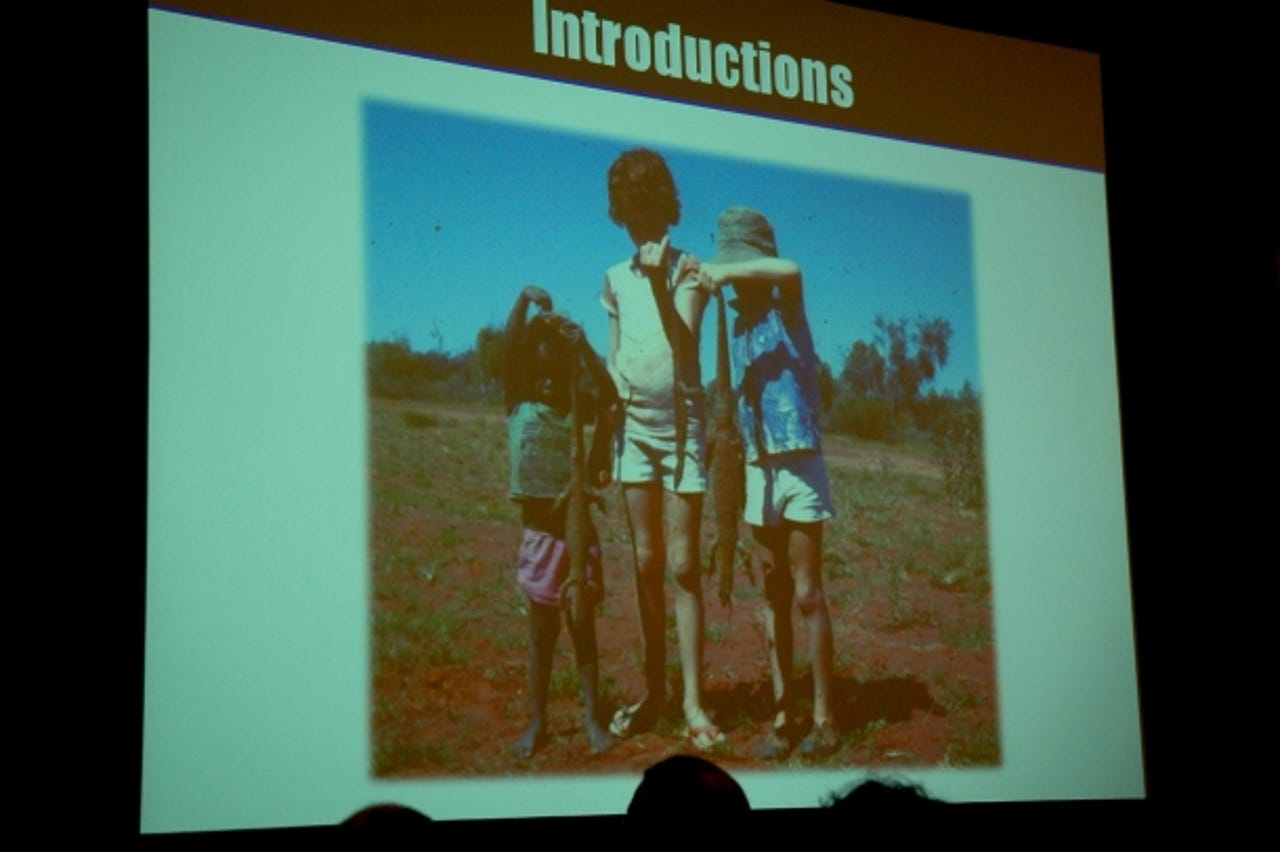

Bell's own interactive experiences have been decidedly non-standard. As the daughter of an anthropologist mother, they spent her early years living with aboriginals in remote Australia "not wearing shoes, learning to get water out of frogs and killing lizards". Things calmed down a bit thereafter; she joined Intel from Stanford in 1998 and has spent the intervening decade peering into people's front rooms and refrigerators around the world.

This has led to a faultlessly multicultural appreciation of how humans actually engage with technology, including insights that may seem trivial, even trite, but are profoundly important in the context of a large company trying to understand people: "Very few things are universal, but I've never been in a house where there hasn't been a fight about the remote control for the TV, nor one where there wasn't a fight over electrical outlets."

Her job now, fortunately for lizards, is to reinvent Intel's approach to product design and teaching it that "TVs are not bigger PCs, mobile phones are not smaller PCs and cars are not PCs on wheels". Which for Intel is something of a culture shock.

"It's about creating a new approach at Intel, so it's asking the right questions for 2020. That way, we can go from Viiv to something more successful, by finding what people love about things. People love TVs, but the moment that your TV asks you to install a driver, or says it's defragging, is a bad moment indeed."

There had already been useful discoveries, she said. "One coup was discovering that we can talk about users the way Intel talks about silicon. You can put them on a roadmap, and they follow the schedule"

"We're marrying social science with engineering. Taking what we know about human beings,. We have a centre of excellence for understanding people, and one for engineering. The lab thinks about human IO, not just computer IO, and running the gamut with new forms of input method, being playful and provocative. Having engineers makes this happen In the next ten years, you will see some very different things from Intel".

Well, that's the sanitised version. What Genevieve Bell the Lizard Killer actually said was all of the above, but with added electric fairies and the origin of Christmas tree lights - she sees many parallels in the early history of consumer electricity and today's spread of the Internet. There were a few pops at British plumbing and showering habits – "The Brits are the only country who'd put the word tepid on a shower tap and, even worse, think this was an experience worth having." – and some home truths for the old Intel and its habit of getting the wrong end of the stick and fashioning it into a platform. "I actually had engineers saying that Intel's task with television was helping its inner PC come out. Can you imagine?"

That's the mark of the true anthropologist, respecting people over institutions. And, as technology becomes embedded ever deeper in our lives, it's the human side of engineering that needs the most love - and has the best chance of repaying that.