Move over HealthKit: Why Apple's ResearchKit is proving the real hit with doctors

HealthKit had a shaky start: the arrival of HealthKit-enabled apps was delayed by days due to a bug, and reviews of Apple's own HealthKit app, Health, were lukewarm.

Unsurprisingly due to the nature of its data, privacy concerns also surfaced around the platform: after launch, Apple warned developers not to store HealthKit data in iCloud after the leak of nude celebrity photos from the service, and banned developers from selling HealthKit data to ad networks.

After these early wobbles, HealthKit looks to be making a slow recovery. Apple CEO Tim Cook told an earnings call in April that around 1,000 apps HealthKit-enabled apps had been published to the App Store - a healthy number, but a tiny percentage of the one million-plus iPhone apps currently available - and added that Los Angeles hospital Cedars Sinai had that month launched a HealthKit app to let patients add health data gathered by their phones to their medical records.

AR + VR

But it's a lesser known companion service to HealthHit called ResearchKit that is also generating a lot of excitement among doctors right now. ResearchKit, launched in March, is a software framework that allows scientists and medical researchers to build apps that can tap into HealthKit to gather health data from iPhone users.

As such, ResearchKit is getting medical researchers fired up and showing the iPhone's potential in the health industry. According to Cook, over 60,000 people have signed up to participate in trials running on the system in the first weeks after it launched - an unheard of number for clinical trials, especially ones that haven't been widely publicised.

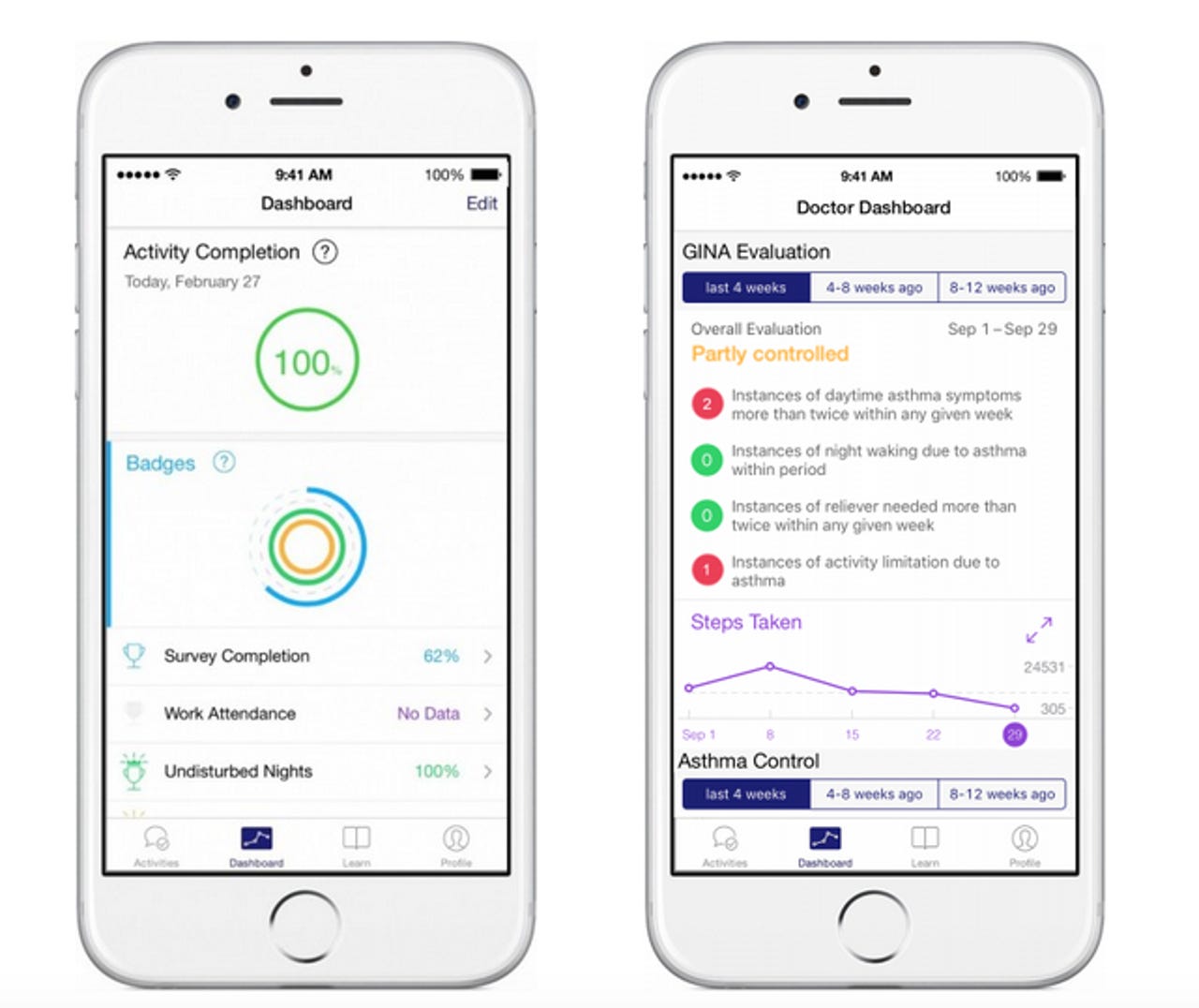

Over 8,600 of those are participating in an asthma study by using the Asthma Health app by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. App users can track their symptoms, get reminders to take their prescription medications, and share data with their doctors.

Using a ResearchKit based app has had obvious advantages for the organisation - not only the volume of participants signing up, but their location, with 87 percent of participants coming from outside the school's local area around New York and New Jersey.

In the six months since the Asthma Health app has been available, it's already throwing up some interesting interim findings.

"The participants using our app on a regular basis reported improved exercise capabilities via surveys, and we saw supporting objective evidence of this finding with a statistically significant increase in step count (as automatically measured by Apple HealthKit) over different time periods and study cohorts," Dr Yvonne Chan, director of digital health and personalised medicine at the Icahn Institute at Mount Sinai, told ZDNet.

The app has also enabled the school to get more people with severe asthma symptoms involved in the research than might otherwise be likely.

"We were able to recruit more patients with more poorly-controlled and severe asthma than one typically expects in a traditional research study. This is an important demonstration of the value of the ResearchKit platform, since traditionally, patients with poorly controlled and severe disease at baseline are more difficult to engage and enroll in clinical trials," Chan said.

Along with Asthma Health, the University of Rochester and Sage BioNetworks' mPower app was one of the first wave of ResearchKit apps. Debuting in April, the app is designed to conduct research into Parkinson's disease by collecting data on the disease's progression - how it affects a person's dexterity, balance, or gait for example.

Dr Ray Dorsey, a neurologist at the University of Rochester who was involved in the creation of the app, said 14,000 people have downloaded it to date. "10 to 15 percent of them have Parkinson's, so in the span of six months this is one of the largest clinical studies of Parkinson's ever conducted," he told ZDNet.

"These individuals are all enrolling without having any conversation with the clinician by and large, this isn't a doctor telling them to sign up for study, this is them going out and deciding to enrol in a research study whenever and wherever they like," he added.

In normal studies, a clinician would walk a would-be participant through the research and gain their consent for their data to be used. It can be a lengthy process with pages of forms to be read and signed.

While ResearchKit studies have done away with that time-consuming consent process, Dorsey believes it's making participants more aware of how the research works and what's happening to their data.

"I think in many ways it's better. Informed consent in a clinic is usually a 20-page document that's unintelligible in many respects and not focused on needs of individuals. In ours, you flick through a screen and it tells you about the risks, it tells you about the benefits, it tells you how long it's going to be, and we're going to protect your privacy to the extent possible but it's not 100 foolproof, and it asks you do you want the data shared or not shared, and provides a number if you want to contact someone. The consent resides on your phone. If you want to stop your participation in the study for any reason, at any point, you can do that. Individuals are far more in control in this study than in any traditional clinical study," he said.

And, like the Asthma Health app, mPower is already generating not only far more data than traditional studies - for some individuals there are as many as 500,000 data points - but also some unexpected findings that non-app research might have missed.

The app can already differentiate those with Parkinson's from those without, and act as diagnostic tool, but also detect pharmacological response to treatment - how individuals respond to the drugs they take - and provide feedback into what's making them better or worse.

Some of that feedback has pointed to a potential link between Parkinson's symptoms and the weather, for example. "I did a quick [medical] literature search on Parkinson's and weather and got nothing... The research is only six or seven months old, but these are whole new avenues of suggestions and areas of investigation that we previously haven't considered," Dorsey said.

Potentially in future Parkinson's research could cross reference any change in symptoms with the user's location and time as measured by their phone and the weather report for that place and see if there really could be a link between the two. It's a level of investigation that simply wouldn't be possible without phones.

For those that have been using ResearchKit and mobile apps to carry out medical research, its potential is clear.

"Open source frameworks such as ResearchKit will transform how we carry out research studies," Chan told ZDNet.

"I don't think we're scratching the surface of what we can do, I don't think we're even close to realising its full potential," Dorsey said.

As Apple looks to grow its place in the enterprise, the health industry is sensible place to start - the IT-enabled healthcare market is expected to be worth over $210bn by 2020. But, as HealthKit's progress to date has shown, winning a part of that market hasn't been an easy home run for Apple. As an open source kit released for scientific research, ResearchKit may not be a massive moneyspinner for Apple, but early results are already proving its worth to the industry. If there's a product that's likely to establish Apple as a player in healthcare, it's ResearchKit, not HealthKit, that's in rude health.

More health and tech stories

- Fitbit's big race: Grow software, services

- Want your heart rate every 10 minutes from Apple Watch? Don't move

- Apple says ResearchKit medical apps must get ethics board approval