Oracle v. Google: Did the jury really understand it?

This morning, my friend Steven A. Shawdecided to take a very unpopular stance regarding the Oracle v. Google trial.

Also Read:

- A litigator's view: Three things I know about Oracle v. Google

- Google kicks Oracle in its patent teeth

Most people who I have spoken to in the computer industry about the trial feel that Google was the stronger party in the case, and that the open sourcing of Java into GPL2 by Sun some years before heavily damaged Oracle's credibility.

While I too have to claim some bias in favor of Google, being an open source advocate myself, I still have a number of reservations about the way the trial itself was conducted, and much of it comes down to the jury selection process and some very unusual biases and lack of expertise that regular off the street folks have about the technology industry.

I've never been a juror in a trial, be it civil or criminal. But like many other people, I've had to report for Jury Duty. In the state of New Jersey in which I currently live, one gets selected typically every four years. Most of the time, you get to wait in a big room all day to see if you're going to be part of a selection process, or even more frequently, you call in that morning to see if they even want you to report to duty at all.

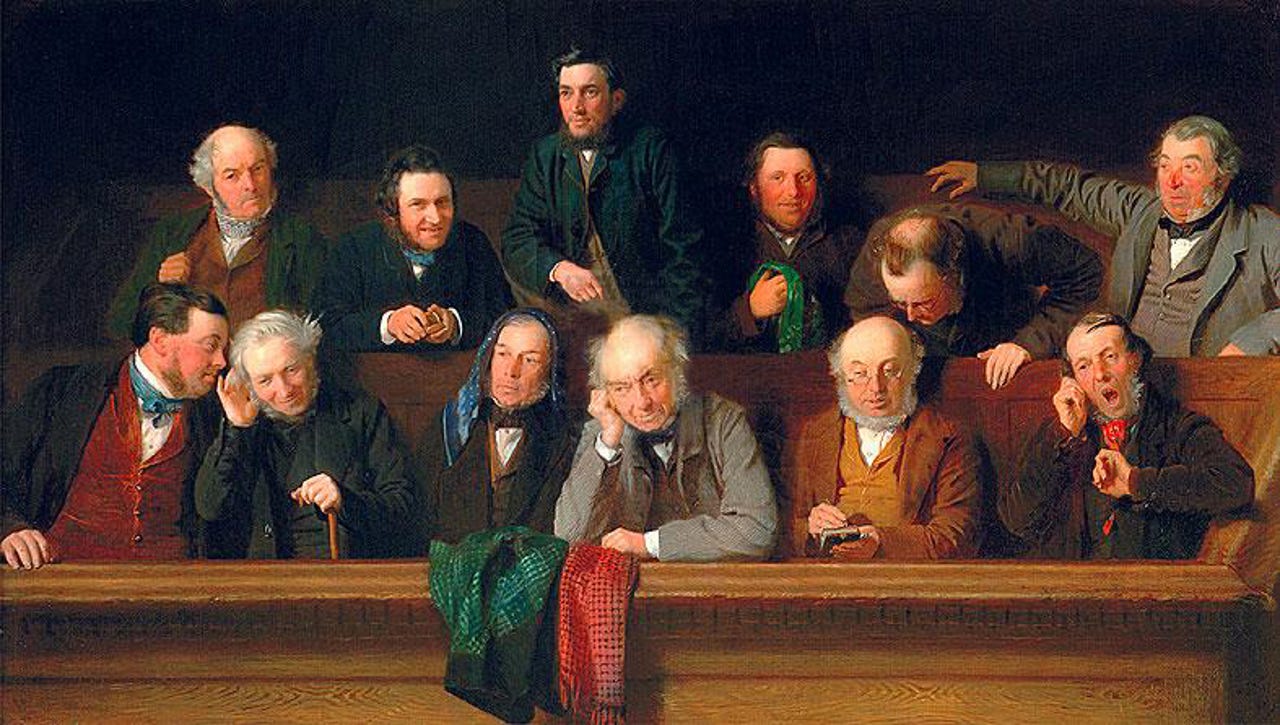

If you do get called in from that waiting room, you then head into an actual courtroom where the attorneys from each side begin the selection process. This process, which is referred to as voir dire, has been in use for many decades.

If you are lucky enough to get called on the stand, they ask you basic stuff like where you live, what you do for a living, and what sort of things you have experience with and even what hobbies and interests you have.

If either sides feel that you have some sort of bias -- and that could be the smallest of biases, such as admitting that you have someone in your family that works in the legal profession, or that you've ever been in a lawsuit of a similar (or dissimilar nature) or if you work in the same or a similar industry as either the plaintiff or the defense, then you can get thrown out.

- Also Read: Oracle v. Google, Winners and Losers

As Rachel King reported this morning on Between the Lines, during the screening process of Oracle v. Google, if you had a technical background, you were excluded as a juror from this trial.

Back in the waiting room you go.

And frequently, many of the most intelligent and educated people do get thrown out, such as medical and technical professionals. Or they find ways to say the right things so they get thrown out, because being on a jury for a few weeks could very well mean losing quite a bit of money for some of these people.

The types of trials I am talking about here are typically small potatoes, 1-week civil trials. Sometimes they can be criminal in nature, and they may last more than a week after jurors are selected. Anyone, and I mean literally anyone, can end up as a juror. It could be a retired schoolteacher, or a blue collar worker. It could be a housewife who never graduated high school.

Now, one would think that these very high profile technology industry intellectual property cases would tend to select more intelligent or educated jurors, or people who at least have a basic understanding of the technology industry. But that's not the case at all.

As Steven told me when I asked him about this last night, the answer is no. That same blue collar worker or retired schoolteacher could very well end up on the same kind of case like this. Like the guy who owns the landscaping business who cuts my lawn, only takes checks, and has someone else do his computer bookkeeping for him.

Or the chimney sweep who checked for a backdraft in my house a few weeks ago who won't own something like an iPhone when I mentioned to him he could take credit cards in the field with one, because he just feels intimidated by computers. He leaves that stuff to his wife.

I'm not saying these folk are dumb people. They aren't. Heck, the chimney sweep knew natural gas boilers like nobody's business and could tell in two minutes that there was no backdraft in my utility closet.

But are people like this really prepared to understand the intricacies of software patents, the nature of Open Source and Application Programming Interfaces, source code and Java class libraries? C'mon. It's difficult enough for your average citizen to understand contract and tort law, let alone participate in something like a murder trial.

See also: Jury strikes a blow against software patents | Google kicks Oracle in its patent teeth | Jury clears Google of infringing on Oracle patents | Oracle v. Google jury stumbling over tech terminology, illness | Copyrights, APIs, and Oracle vs Google | CNET: Complete trial coverage

I'm not sure even someone like myself who has over 20 years of experience in systems integration and analysis and has worked with Java and embedded devices is prepared to understand all these things, because I'm not a programmer.

Ars Technica has an interesting piece that was published yesterday about the behind the scenes jury activity in the Oracle v. Google trial. One of the things I thought was very interesting was that some of the jurors were actually put off by Google's lawyers using as evidence Sun Microsystems' CEO Jonathan Schwartz's congratulatory post which he published on his corporate blog praising Google for their launch of Android.

They felt, apparently, that "We felt like it wasn't a good business practice to rely on a blog," and that "Some of us had an underlying feeling that Google had done something that wasn't right."

That disturbs me on a number of levels -- especially that the jurors would feel was a corporate blog post written by the CEO of a major technology company shouldn't be used as evidence and that blogs were unprofessional.

To me, that displays an inherent bias that could really only be held by people who aren't familiar with how business communications are evolving, and how important blogs and extranets are for companies to project their image and their official opinion on any number of strategic matters of importance to them.

If something like an official corporate blog post didn't seem right to the jury for Google's lawyers to use as evidence, what the hell else are they missing here? I suspect a great deal more.

Are off the street jurors really equipped to understand the complexities of intellectual property litigation in the technology industry? Talk Back and Let Me Know.