Research: 1.3 million malicious ads viewed daily

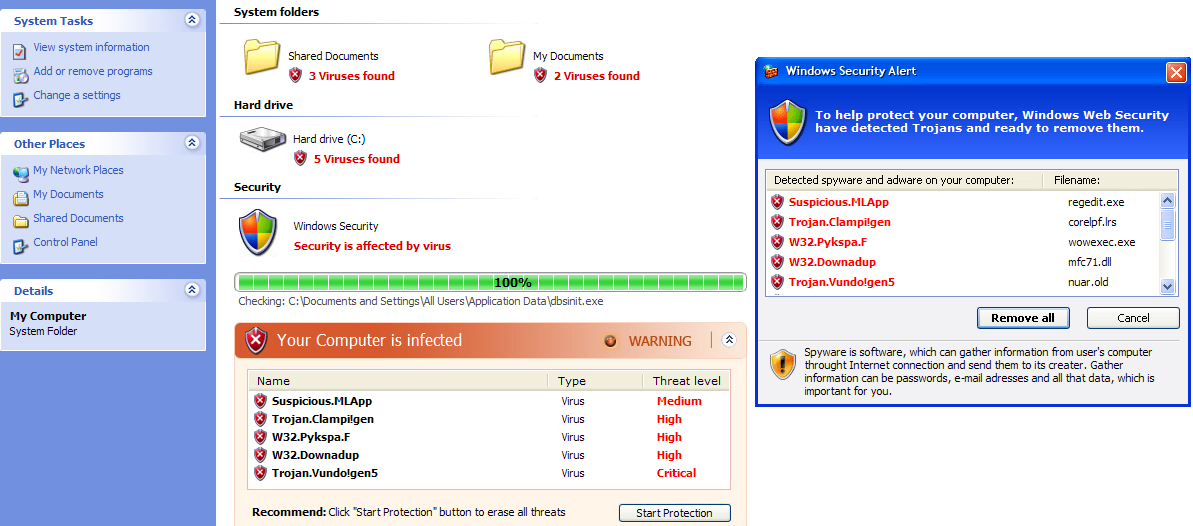

New research released by Dasient indicates that based on their sample, 1.3 million malicious ads are viewed per day, with 59 percent of them representing drive-by downloads, followed by 41 percent of fake security software also known as scareware.

The attack vector, known as malvertising, has been increasingly trending as a tactic of choice for numerous malicious attackers, due to the wide reach of the campaign once they manage to trick a legitimate publisher into accepting it.

More findings from their research:

- The probability of a user getting infected from a malvertisement is twice as likely on a weekend and the average lifetime of a malvertisement is 7.3 days

- 97% of Fortune 500 web sites are at a high risk of getting infected with malware due to external partners (such as javascript widget providers, ad networks, and/or packaged software providers)

- Fortune 500 web sites have such a high risk because 69% of them use external Javascript to render portions of their sites and 64% of them are running outdated web applications

The research's findings are also backed up by another recently released report by Google's Security Team, stating that fake AV is accounting for 50 percent of all malware delivered via ads.

The increased probability of infection during the weekend can be attributed to a well known tactic used by the individual/gang behind the campaign. Once the social engineering part takes place, in an attempt to evade detection, they would first feature a legitimate ad, wait for the weekend to come thinking that no one would react to the attack even if it was reported, and show the true face of the campaign.

Case in point is NYTimes malvertising campaign (Sept. 2009):

The creator of the malicious ads posed as Vonage, the Internet telephone company, and persuaded NYTimes.com to run ads that initially appeared as real ads for Vonage. At some point, possibly late Friday, the campaign switched to displaying the virus warnings. Because The Times thought the campaign came straight from Vonage, which has advertised on the site before, it allowed the advertiser to use an outside vendor that it had not vetted to actually deliver the ads, Ms. McNulty said. That allowed the switch to take place.

Why would a malicious attacker engage in malvertising attacks, compared to relying on hundreds of thousands of compromised sites?

Malvertising is not an exclusive practice used by a team of cybercriminals specializing it in. It's done in between the rest of the malicious campaigns and activities the gang/individual is involved into.

From a cybercriminal's perspective, a high trafficked web site would naturally mean greater click-through rates, or as we've seen in previous cases, actual pop-ups of the ubiquitous fake scanning progress screen. Moreover, when direct compromise of this host cannot take place, they would attempt to locate and abuse the weakest link in the trust chain, in this case the third-party advertising network having access to the site. The problem then multiplies due to the re-syndication of the ad inventory from a particular publisher to another.

- Related posts: Fake Antivirus XP pops-up at Cleveland.com; Scareware pops-up at FoxNews; Gawker Media tricked into featuring malicious Suzuki ads; MSN Norway serving Flash exploits through malvertising

One of the main problems publishers face, is that in order to stay competitive in the marketplace, they emphasize more on the efficiency of acquiring new customers, compared to the security practices that would prevent such a attack from taking place, and clearly that also includes the use of commercialanti-malvertisingsolutions.

This efficiency vs security approach can be best seen in a major malvertising campaign profiled in February, 2010, where the malicious attackers targeted as many efficiency-centered publishers as possible, successfully infiltrating known services, such as DoubleClick and Yieldmanager.

In terms of protection from an end user's perspective, Windows users browsing the Web in a sandboxed environment, using least privilege accounts, NoScript for Firefox, and ensuring that they are free of client-side exploitable flaws, will mitigate a huge percentage of the risk.

Have you been a victim of malvertising? When and where was the last time you were exposed to a bogus scareware "You're infected" pop up? Who should be held responsible, the publisher for accepting the ads and the lack of automatic malicious content scanning mechanisms, the site that featured it, or the end user for his lack of situational awareness on what malvertising and scareware is in general?

Talkback, and share your opinion.