Social engineering in action: how web ads can lead to malware

One of the great myths of security in 2011 is that if you’re infected with malware it’s your own fault. You shouldn’t have been searching for porn, downloading pirated software, or snagging bootleg DVDs from BitTorrent.

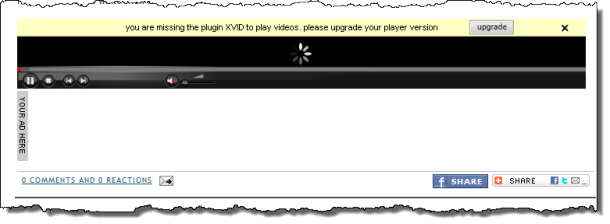

As I found out firsthand this week, even a completely innocent link can lead to unwanted, potentially malicious software. In this case, the delivery mechanism was this ad, which I found when I visited a lightly trafficked but legitimate blog (I’ll leave them unnamed, because they’re innocent victims in all this).

The ad appeared at the bottom of a post, with an animated graphic and a yellow bar designed to mimic the appearance of similar “missing plugin” messages from browsers. The ad was served by a third-tier ad network, AdBrite.

For more screens showing exactly how this scam works, see the companion photo gallery, "How ads on legitimate web sites can lead to malware and unwanted software."

Clicking the ad takes you to a page that uses similar social engineering to simulate the experience of a missing codec. The spinning wheel next to the word “Buffering” suggests that the page is trying to download a video but is being stopped somehow.

Although this screen was captured in Google Chrome, the experience is identical in other browsers, including Internet Explorer.

The social engineering is decent. Xvid is a legitimate video codec, and the logo in the top left corner of the page is the same one used by the group that officially maintains the codec. Clicking anywhere on the page results in an executable file called XvidSetup.exe being downloaded.

What happens if you run that file? More social engineering.

- The installer certainly looks legitimate, and it even offers a choice of Express or Custom installations.

- The setup file does not have a digital signature.

- It does appear to install a version of the Xvid codec, but the installer omits the GNU General Public license that is required by the Xvid team.

Regardless of which option you choose you also get a few extras you didn’t count on:

- It installs Real Player, using an affiliate code that no doubt nets the distributors a commission on the installation. On at least one occasion, it performed a reinstallation even after I clicked Cancel.

- It downloads additional software and silently installs add-ons for all browsers it detects on your system, including Internet Explorer, Firefox, and Chrome.

This status dialog box goes by very quickly, but you can clearly see what it downloads and installs.

If you look in Firefox, Chrome, Safari, or Internet Explorer, you'll find that several add-ons have been silently installed as well.

At no point during this installation process was I offered a license agreement or given any option to consent to the extras being installed. And even clicking the link on the initial setup screen provides no information about what the offered programs are, who they’re from, or what they do.

After installation, are there any additional clues about what just happened? Not really. The spoftware is listed in Control Panelbut there's no publisher name for the “enhancements” nor are there help and support links.

If you’re looking for the real Xvid codec, by the way, you can find it here. The Windows installer file contains the most recent version of the codec, is digitally signed, and presents a proper GPL license during installation. It also identifies itself properly in Control Panel.

Page 2: What’s the threat? -->

<-- Previous page

So what do these mystery programs do? Are they malicious? Do they steal personal information? Do they display pop-ups?

A couple months ago, Jerome Segura of Pareto Logic analyzed a nearly identical scam (same graphics, similar domain name) and found plenty to be suspicious of:

After installing the “codec” you can return time and time again to the site but you won’t see any video… And that’s where the trick is…

In the meantime, unwanted components have been installed on your computer, such as this Browser Helper Object (BHO) …

What I installed here is different from that package, even if the delivery mechanism is nearly identical. Initially, at least, these browser add-ons appear to do nothing at all. I suspect they’re time-bombed, waiting a few days (or even a month) before triggering their payload.

I did find one giant clue, though, when I clicked the “Installing and Uninstalling” link at the bottom of the page that’s serving up this software. That led to a plain-text page, a portion of which is shown here:

ClickPotato? If that name sounds familiar, it might be because you read this post a couple weeks ago: Trojans, viruses, worms: How does malware get on PCs and Macs? Among the top 10 threats to consumer PCs identified by Microsoft in 2010 was this one:

ClickPotato is a relatively new family of “multi-component adware” that displays pop-ups and ads. It often tags along with Hotbar.

The fact that the distributors of this software bundle are using a template that includes ClickPotato should be a big red flag. I found a few other red flags by inspecting the source code of the landing page, which includes a link to a site called myroitracking.com. According to the Google Safe Browsing service, this domain is a well-known intermediary in the distribution of malware:

Has this site acted as an intermediary resulting in further distribution of malware?

Over the past 90 days, myroitracking.com appeared to function as an intermediary for the infection of 106 site(s).

I observed the behavior of this ad and the landing page over a period of several days. During that time I exchanged several e-mails with the AdBrite Trust & Security team, which initially denied that there was anything wrong with the ad. They finally agreed to investigate after I sent them a report from VirusTotal showing 9 separate detections as malware along with screenshots showing both Norton Internet Security and Microsoft’s SmartScreen blocking the file.

Within 30 minutes, the code at the landing page had been scrubbed, removing the deceptive “missing plugin” references, deleting the link to ClickPotato, and providing a link to an alternate download site with a recompiled file of the same name. It will take the antivirus companies a few days to catch up, at which point a new version will probably appear.

The gang behind this scam appears to have tried to cover up its tracks—but you can bet they’re not out of business. I hope this story makes it possible for you to recognize them if they cross your path.